Nestled within one of Europe’s most densely populated regions, the Campi Flegrei caldera is a volcanic system whose secular unrest shapes the daily life of its inhabitants. Here, during the last decade and still ongoing crisis, ground uplift, frequent earthquakes, and persistent gas emissions interact to create a complex, evolving multi-risk environment. These natural hazards rarely follow simple patterns: they overlap, cascade, or unfold independently, challenging scientists, authorities, and communities alike. As the ongoing unrest intensifies, long-standing questions about forecasting, preparedness, and communication, living with Campi Flegrei becomes an exercise in balancing uncertainty with resilience. This opinion article reflects on that challenge and its implications for the future of risk governance in Naples.

On the western edge of Naples, Italy, life unfolds in the shadow of a restless giant. The Campi Flegrei caldera—“the burning fields”—has simmered for millennia. Its cratered landscape tells stories of colossal eruptions in the distant past, but today, the concerns are less about catastrophic explosions and more about how science, society, and governance can cope with uncertainty.

When the ground trembles or rises by a few centimetres, when sulfurous gases seep from fumaroles (natural openings in the ground that release steam and volcanic gases in Pozzuoli), anxiety spreads. Is this the prelude to a possible eruption—or just another episode in the restless breathing of the caldera? For scientists and authorities, the answer is rarely straightforward.

Decades of unrest: ground deformation and seismicity at Campi Flegrei

The Campi Flegrei volcanic field, located in the western sector of the densely populated metropolitan area of Naples, is a large caldera formed by two major explosive eruptions that occurred approximately 39,000 and 15,000 years ago [1]. Over the past 10,000 years, the caldera has experienced more than 70 eruptions, the most recent of which occurred in 1538 after about four millennia of dormancy, creating the small volcanic cone of Monte Nuovo, 170 meters high [2]. Since then, the volcano has remained in a state of unrest rather than true quiescence, characterised by recurrent ground deformation and seismic activity that reveal its persistent internal dynamics. The most prominent manifestation of this activity is the phenomenon of bradiseism—a slow, meter-scale vertical uplift and subsidence of the caldera floor centred near the town of Pozzuoli [3]. This deformation reflects fluctuations in the pressure and movement of magmatic and hydrothermal fluids beneath the surface. During the last fifty-five years, three major uplift crises have occurred: in 1970–72, 1982–84, and from 2009 to the present [4] [5]. The earlier two episodes produced vertical uplifts of about 1.0 and 1.8 meters, respectively, while the current one has exceeded 1.5 meters as of September 2025, with an ongoing time-variable rate of 1 to 3 centimetres per month.

Over the past decade, Campi Flegrei has recorded more than 50,000 earthquakes, most of them small in magnitude but significant in their spatial and temporal clustering. Seismicity defines a roughly ellipsoidal pattern following the inner ring structure of the caldera, corresponding to the area of maximum uplift [6] [7]. High-resolution geophysical imaging has revealed a complex subsurface architecture composed of a gas-rich reservoir located at depths of 2–4 kilometres, capped by a deformed and relatively impermeable rock layer between 1 and 2 kilometres, and underlain by a deeper basement below 3.5 kilometres [8]. Most earthquakes occur between 1 and 4 kilometres depth, particularly beneath Pozzuoli and the Solfatara–Pisciarelli geothermal area, where the intense interaction between the gas-charged reservoir and the fractured caprock promotes fluid migration and seismic swarms [8].

Since 2019, seismic activity has intensified in both frequency and magnitude, extending offshore along faults that mirror the inner caldera boundary. The Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) catalogue reports three earthquakes exceeding magnitude 4.0, including a compound event on March 13, 2025 (Md 4.6), which actually consisted of two nearly simultaneous shocks of Mw 3.3 and Mw 4.0. The largest ruptures have occurred on high-angle, near-vertical normal faults trending east–west near Baia–Bacoli and north–south near La Pietra, reflecting regional extension and uplift dynamics. These seismic and deformation patterns support a model in which the ongoing unrest is primarily driven by variations in pressure and stress within the shallow hydrothermal–magmatic system, which affect pre-existing fault structures. Progressive depressurisation of the gas-rich reservoir modifies the mechanical state of the overlying crust, promoting fault slip and recurrent uplift episodes. Overall, Campi Flegrei today remains an active and evolving caldera where ground deformation, fluid migration, and fault reactivation coexist in a delicate equilibrium, underscoring the persistent volcanic and earthquake hazard in one of the most densely inhabited volcanic areas on Earth [9].

Effects of ground uplift, earthquake damage on buildings and gas emissions during the ongoing volcanic unrest at the Campi Flegrei caldera. From the top to the bottom images. At the small fishermen’s harbour at the foot of the Rione Terra in the town of Pozzuoli, the uplift of the ground has drained the harbour’s waters, and the former sea levels before the bradyseismic crises of the past 45 years are clearly visible on the old docking piers. The Temple of Serapis in Pozzuoli serves as a natural “gauge” of the bradyseism at Campi Flegrei. Built in the 2nd century AD, its marble columns show holes made by marine molluscs, marking past sea levels and revealing cycles of ground uplift and subsidence over the past two millennia. The strong ground shaking caused by the M 4.4 May 20, 2024, earthquake has caused minor to moderate damage to buildings located in the near-epicentre area. The crater of the Solfatara volcano shows evidence of fumaroles that are vigorous vents releasing high-temperature steam and sulfur-rich gases from shallow hydrothermal systems. (Image credit: A. Zollo, G. Zuccaro)

More than a volcano

Unlike the iconic cone of nearby Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei is not a single cone but a sprawling volcanic depression where multiple hazards intersect. Land uplift (bradiseism), swarms of earthquakes, potentially toxic gas emissions and the remote but catastrophic possibility of an eruption coexist. Sometimes these hazards occur and unfold independently; sometimes they cascade, one triggering another.

This makes Campi Flegrei not just a volcanic system but a multi-risk environment. It’s not just one risk; it’s many risks tangled together. That entanglement complicates both forecasting and response.

The scientific infrastructure monitoring Campi Flegrei is one of the most advanced in the world [10]. Seismic networks, satellite-based ground deformation measurements, gas monitoring stations, and geochemical sampling provide near-continuous-time streams of data. But translating this flood of information into clear predictions is far from easy.

Models must integrate geophysical, geochemical, and structural data while updating in real time as conditions evolve. Yet the path of science often collides with the urgency of a crisis. Validation, peer review, and careful interpretation take time. Civil Protection, on the other hand, must act on timescales of days, weeks, and months.

The question is raised whether we can afford to spend years perfecting a model when decisions must be made in real time, as emergency planners require. Bridging the gap between cutting-edge research and operational readiness remains one of the central challenges.

The decision-making dilemma

When earthquakes shaking rattle buildings in Pozzuoli or the ground swells visibly, authorities face a stark question: should people be evacuated, interpreting these phenomena as precursors of an impending eruption? Evacuation is the only viable protection if an eruption occurs, but past unrest episodes—in the 1950s, 1970s, and 1980s—ended without one. Each “false alarm” makes the next decision harder, fueling scepticism among residents and political hesitation among decision-makers.

But false alarms erode trust; missed alarms could cost lives. To move beyond this binary framework, experts are introducing new operational concepts such as “bradiseism risk,” recognising that ground uplift and earthquakes themselves justify protective measures even when an eruption is not imminent.

If uncertainty is inevitable, preparedness is the most reliable form of resilience. Many buildings in the Campi Flegrei area are vulnerable to seismic shaking, and retrofitting programs are urgently needed. A systematic census of high-risk structures, backed by financial mechanisms to co-fund upgrades, is essential.

Emergency plans, too, must be dynamic. Static protocols risk becoming obsolete in the face of an evolving unrest scenario. Preparedness cannot be improvised in the heat of a crisis—it must be built during quiescent phases.

The communication trap

For many residents, “volcano” means one thing: eruption. Explosions, ash clouds, and pyroclastic flows dominate the public imagination, while other hazards—earthquakes, toxic gases, and land uplift—receive far less attention, despite their immediate impacts.

Indeed, at Campi Flegrei, one of the main challenges we face is that this is a true multi-risk system: earthquakes, ground uplift, gas emissions, and a possible eruption. Communicating this complexity in a way that is simple, consistent, and trustworthy is not easy. People tend to focus only on the eruption scenario, while the risks that actually impact daily life—like seismic shaking or land instability—are often underestimated. And when different maps, zones, or alert levels overlap, confusion can grow, and trust may erode.

These communication challenges are not unique to Campi Flegrei. They echo other domains: climate change, pandemics, and earthquake forecasts. In each case, science advances rapidly, often with contradictory findings, while decision-making must act under uncertainty and time pressure. The gap between evolving knowledge and urgent choices is exactly where communication tends to falter.

Building authoritativeness through trust

Improving communication is not only a matter of messaging, but of building credibility and authority over the long term. Experts highlight four key steps:

- Clarity and consistency of messages between scientists, civil protection, and institutions.

- Transparency about uncertainty, communicating not just what is known but also what is not.

- Tailored communication, adapted to the needs of decision-makers, the general public, and local communities.

- Trust-building during quiet times, with messages that emphasise preparedness and resilience rather than only the dramatic eruption scenario.

In short, at Campi Flegrei—and in any multi-risk setting—communication is not just about explaining hazards. It’s about building trust, transparency, and preparedness. That is what makes science authoritative, and what turns scientific knowledge into real impact for society.

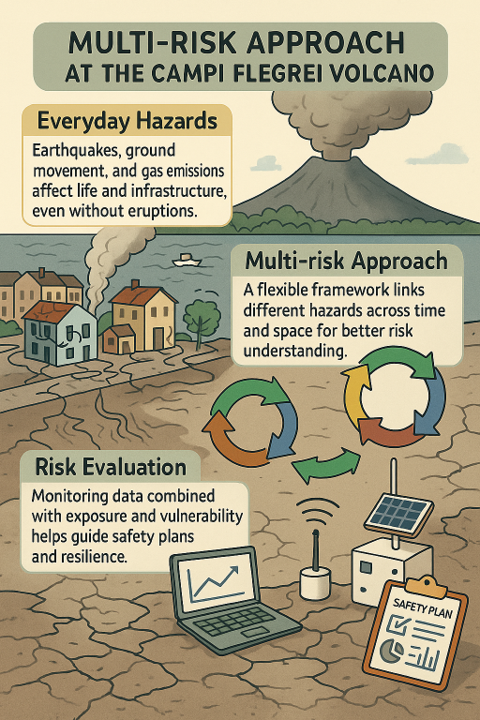

Illustration of the multi-risk approach applied at the Campi Flegrei volcano. Everyday hazards such as earthquakes, ground deformation, and gas emissions interact within a complex volcanic system. A multi-risk framework links these different hazards across time and space, improving understanding and decision-making. By integrating monitoring data with assessments of exposure and vulnerability, authorities can better evaluate risk and develop effective safety plans for communities living within the caldera (image created with ChatGPT 5.0).

Living with uncertainty

Campi Flegrei will likely never be risk-free. The challenge is to live with a volcano whose unrest may last years, decades, or even centuries. Meeting that challenge requires:

- integrated, continually updated multi-hazard assessments;

- stronger pipelines between monitoring and decision-making;

- long-term investments in infrastructure; and, above all, communication strategies that maintain public trust.

Uncertainty cannot be eliminated—but it can be managed. And in the densely populated landscape of Naples, where half a million people live within the caldera, managing uncertainty is not optional. It is the only path to resilience.

This contribution is an expanded note built upon the intervention as panellist of the Opening Session – Round Table “Geoscience in the public eye: Bridging the gap between Science and Society for Trust, Transparency and Impact” at the EAGE Near-Surface Geoscience meeting, Naples, 7-9 September 2025

References

- Orsi, G. Volcanic and deformation history of the Campi Flegrei volcanic field, Italy. In G. Orsi, M. D’Antonio, & L. Civetta (Eds.), Campi Flegrei: A restless caldera in a densely populated area, active volcanoes of the world. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37060-1 (2022).

- Isaia, R., P. Marianelli, and A. Sbrana (2009), Caldera unrest prior to intense volcanism in Campi Flegrei (Italy) at 4.0 ka B.P.: Implications for caldera dynamics and future eruptive scenarios, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L21303, doi:10.1029/2009GL040513.

- Bevilacqua, A., Neri, A., De Martino, P. et al. Accelerating upper crustal deformation and seismicity of Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy), during the 2000–2023 unrest. Commun Earth Environ 5, 742 (2024).

- Troise, C., De Natale, G., Schiavone, R., Somma, R., Moretti, R. The Campi Flegrei caldera unrest: Discriminating magma intrusions from hydrothermal effects and implications for possible evolution. Earth-Science Reviews, 188, 108–122 (2019).

- D’Auria, L., et al. 2011. Repeated fluid-transfer episodes as a mechanism for the recent dynamics of Campi Flegrei caldera (1989–2010). J. Geophys. Res. 116, B04313 (2011).

- Scotto di Uccio, F. S., et. al. Delineation and Fine-Scale Structure of Fault Zones Activated During the 2014–2024 Unrest at the Campi Flegrei Caldera (Southern Italy) From High-Precision Earthquake Locations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51(12), e2023GL107680. (2024).

- Tan, X., Tramelli, A., Gammaldi, S., Beroza, G.C., Ellsworth, W.L., Marzocchi, W., 2025. A clearer view of the current phase of unrest at Campi Flegrei caldera. Science eadw9038. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adw9038

- De Landro, G., Vanorio, T., Muzellec, T. et al. 3D structure and dynamics of Campi Flegrei enhance multi-hazard assessment. Nat Commun 16, 4814 (2025).

- Iervolino, I., Cito, P., De Falco, M., Festa, G., Herrmann, M., Lomax, A., Marzocchi, W., Santo, A., Strumia, C., Massaro, L., Scala, A., Scotto Di Uccio, F., Zollo, A., 2024. Seismic risk mitigation at Campi Flegrei in volcanic unrest. Nat Commun 15, 10474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55023-1

- Bianco,F., Caliro,S., De Martino, P. et al. (2022), The Permanent Monitoring System of the Campi Flegrei Caldera, Italy,” in Orsi, G., D’Antonio, M., Civetta, L. (Eds.), 2022. Campi Flegrei: A Restless Caldera in a Densely Populated Area, Active Volcanoes of the World. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37060-1

Post edited by Asimina Voskaki, Hedieh Soltanpour and Navakanesh M Batmanathan

Faculty of letters and Languages

Living with the restless Campi Flegrei caldera involves managing a complex, evolving multi-risk environment, including persistent ground uplift, frequent shallow earthquakes, and gas emissions. Over 500,000 residents live in the high-risk, densely populated, and historically significant area. Effective communication and spatial planning are essential to manage volcanic crises and improve risk awareness.

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

is an important and useful topic. I have benefited greatly from the information that has been published.

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

This was a great read—very helpful

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

So much beauty with so many ideas