Before continuing, if you haven’t read it yet, catch up with the first part of this blog article by clicking on this link.

The good

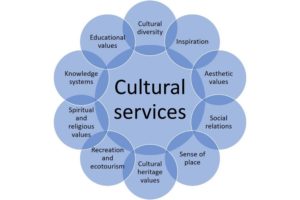

Living with volcanoes is not all bad. Volcanoes provide a wealth of natural resources in the form of building materials, hot springs, freshwater and fertile soil. However, there are more hidden aspects, which was the focus of a recent collaboration with an archaeologist. We believe that volcanoes and their landforms provide “cultural services”, which is a component defined by the UN Millennium Ecosystem Assessment as the cultural benefits we gain from ecosystems. These components are the following:

Cultural ecosystem services, as part of the UN Millennium Assessment.

This is of interest to me as a social volcanologist, as I could see the ways that volcanoes can fit into all of these categories. Volcanoes inspire our artistic expressions with their aesthetic values, which can benefit our wellbeing. They provide a sense of place and a focal point of fostering and maintaining social relations before, during and after an eruption through social cohesion and other resilience factors. They provide educational value for students, adults and researchers, which help develop our knowledge systems of how volcanoes work.

Volcanoes are brilliant recreation and ecotourism options (if the place is safe enough) and whether it is visible or not, they are a source of spiritual and religious value. All this together, with the differences in each society and volcano around the world, creates cultural diversity and heritage. For the project, we focused on combining cultural heritage and geoheritage of Soufrière Hills Volcano on Montserrat, La Soufrière St. Vincent, Vesuvius in Italy and the Laacher See in Germany, to show the positive ways these sites of past traumas can be used to educate people [1].

La Soufrière Natural Trail. Photo taken by Jazmin Scarlett, 2016.

There are other positives that are often neglected in the media, as they focus more on the negatives. An extraordinary thing that happens during a volcanic eruption, and indeed for other natural hazards, is the different ways community resilience manifests. For St. Vincent, there are a number of examples that demonstrate people coming together to cope with the eruptions of La Soufrière. In 1902, there is a photograph (below) of a group of people moving a hut from one location to another. Digging in the archives, I found this was a result of villagers of two villages close to La Soufrière receiving permission from the colonial government to temporarily move south to avoid the volcanic hazards. This coming together is called “social capital” and is ultimately based on trust, utilising the resources and skills people have to help during times of crisis.

Another positive aspect is “social networks”, for St. Vincent this was in the form of inhabitants in the north of the island, closer to the volcano, that temporarily moved with family and friends in the south of the island. Social networks are also used to acquire building resources and have a greater chance of getting back on their feet. The last example is another social capital factor, called “swap labour”. A man I interviewed who lived in the closest village to the volcano, returned home after the eruption and assisted people in the village with outstanding tasks they had, in return he would get food and help with any tasks he had.

“Moving house to (or from) site” by Tempest Anderson, 1902. Used with permission from the Yorkshire Museum.

The unpredictable

Volcanology is a science based on geological and geophysical interpretation, probability and forecasting. Maybe we will reach a point where we can truly say with 100 % certainty how, why, when, what a volcanic eruption will do and the impact of the related volcanic hazards, but it will take a long time to get there. When there is uncertainty and unpredictably, hopes, fears and rumours can fill that void, if the science cannot keep up.

Our individual perceptions of hazard and risk can influence our own self-efficacy (confidence to prepare) to a volcanic eruption. There are socio-economic, political, environmental and health-related factors that have an impact on people’s capacity to respond to an eruption. I have interviewed people who lived in the same town of the last eruption of La Soufrière in 1979 but had different experiences. One had access to a vehicle and was able to stay with friends in the south of the island. On the other hand, different families did not have a vehicle and walked 3 km to the nearest town and then one had to come back to collect clothes etc. Our own circumstances, as well as the potential sudden changes a volcanic eruption can take, make responses unpredictable.

The role of media can also skew uncertainty. There are many recent and historical examples where the media announced that an “imminent” eruption is about to take place, which will be catastrophic and will cause panic and chaos. These alarming headlines more often than not, actually make a volcanic crisis worse. People living with volcanoes do so through resilience and adaptation and are generally more accepting of both the destructive and creative effects, once described as “Paradise Tax”.

The “panic” is a common disaster myth that is also portrayed every single time on film. Yes, our rationality can be disrupted when a volcanic eruption occurs, but because of our education, knowledge, experience, drills, mitigation efforts and preparedness as a society, we do usually respond appropriately. Despite the deaths caused by the 1812 and 1902-1903 eruptions of La Soufrière, in each event, people appropriately and promptly evacuated away from the volcano, further south and in some cases, even to the nearby islands of Bequia, Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago.

Conclusions

The historical and social approach to volcanology is not new, but the methods used are only starting to gain strength. The human perspective of living with volcanism is just as vital to understand as the geology of the volcanoes. Focusing on the negatives and positives of living with volcanoes, we can see how, essentially, each volcanic society is unique from one another, and this, therefore, makes it important to research and assist in preparedness and resilience activities for potential future events. But remembering actions should be tailored depending on the characteristics of the society. When looking back at the history of societies and volcanic eruptions in many parts of the world it is therefore important to investigate the impacts of colonialism, as this shaped what the societies are today.

Bibliography

[1] Scarlett J.P. and Riede F. (2019) The Dark Geocultural Heritage of Volcanoes: Combining Cultural and Geoheritage Perspectives for Mutual Benefit. Journal of Geoheritage. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-019-00381-2

About the author

Jazmin Scarlett studied BSc (Hons) Geography and Natural Hazards at Coventry University and MSc Volcanology and Geological Hazards at Lancaster University, where she did a social volcanology dissertation investigating the volcanic risk perceptions of La Soufrière St. Vincent, where her family is from. She has recently passed her PhD in Earth Science at the University of Hull specialising in historical and social volcanology, titled: “Co-existing with volcanoes: the relationships between La Soufrière and the society of St. Vincent, Lesser Antilles”. Her broad research interests are human-volcano interactions, focusing on risk, vulnerability, resilience, perceptions, culture, heritage and education. She is now a Teaching Fellow in Physical Geography at Newcastle University and starting a small research project investigating the mental health impacts of professionals who communicate risk.

Post edited by: Giulia Roder, Valeria Cigala and Gabriele Amato