As natural hazard scientists, we often emphasise the concept of exposure – how much people, infrastructure, and ecosystems are in harm’s way when close to natural hazard sources (e.g., floodplains, volcanoes, or fault lines). The closer you are, the higher the risk. Therefore, one of the main goals in natural risk assessment is to reduce exposure whenever possible. We advocate for informed planning, avoiding high-risk areas, and making space safer through sustainable design. However, a visit to a place like Kagoshima challenges that narrative.

In Kagoshima, exposure is not just about those red-coloured zones on a risk map – it is a way of life; it is waking up to ashfall, carrying an umbrella for volcanic dust, and regularly hearing eruption alerts on your phone. It is built into the routines, architecture, and mindset of the people who live there. This blog is about my experience visiting Kagoshima – a personal effort to understand how people manage to live alongside an active volcano. What is life really like in such a hazardous zone? Why would anyone choose to live in the constant shadow of a potential eruption? And what measures have been taken to protect the community? While some of the facts presented here are based on published research, others are derived from my own observations, my casual conversations with residents (word of mouth), and information shared in public leaflets I collected during my visit.

Built in the shadow of Sakurajima

The city of Kagoshima is situated on the southern edge of Japan on the island of Kyushu. The city has grown around one of Japan’s most active volcanoes, Sakurajima; a terrifying sight for visitors, but a blessing in the eyes of the locals. Sakurajima lies about 4 to 10 kilometres from Kagoshima, depending on the reference point (roughly 4 km from the shore and around 10 km from the city centre to the volcanic crater). As I walk along the Kagoshima shore, looking at Sakurajima – so close to the city, constantly belching smoke and ash, I cannot help but wonder how people manage to live here without a constant fear of eruption.

Residents calmly watching Sakurajima erupt – a quiet moment in a city shaped by resilience (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour)

This active stratovolcano poses multiple risks to nearly 1.6 million residents in the Kagoshima prefecture [1]. The last major eruption, known as the Taisho eruption, occurred on January 12, 1914, sending an eruption column over 8000 meters into the sky. Due to this eruption, a massive lava flow connected the volcanic island of Sakurajima to the Ōsumi Peninsula to the east. An ancient shrine named Tsukiyomi and an entire village were buried beneath the lava. What made me even more uneasy as a tourist was learning that this is not the only volcano in the area. There is also a highly active submarine volcano, called Wakamiko Caldera, located in the northeastern part of Kagoshima Bay. Since Mt. Sakurajima and Wakamiko share the same magmatic source, an increase in activity at Sakurajima could also signal a potential surge in activity at Wakamiko [4].

A three-dimensional topographic model depicting Sakurajima and the coastline where Sakurajima is now connected to the Ōsumi Peninsula due to past eruptions (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour from Sakurajima visitor centre)

Coexisting with the volcano

Eruptions have become a part of the ordinary daily life of the residents of Kagoshima and Sakurajima. Ash falls can be seen almost everywhere. It might seem surprising, but many people in Kagoshima do not just live with Sakurajima – they feel a deep connection to it. The volcano has become the main character of the city, being an integral part of the residents’ identity, culture, and even affection. You can hear it in how locals talk about the volcano, often personifying it. The image of Sakurajima with a human-like face appears in many spots – as if it is a living presence, a companion, even a protector. People believe Sakurajima is usually calm and even offers blessings. Yet, at times, it reminds them of its immense power with a massive eruption. There is a sense of awe and faith in the way they coexist with this volcano. Sakurajima has also been a source of inspiration, from everyday crafts to even poetry. As quoted on one of the signs near the volcano, a famous Japanese haiku was written by Mizuhara Shuoshi after she witnessed a powerful eruption, which for her evoked a masculine energy. Interestingly, the haiku was composed on May 5th – now celebrated in Japan as Tango no Sekku (Boy’s Day), a festival wishing strength and courage to boys.

A few examples of Sakurajima’s presence in daily life, from street art and signs to themed souvenirs and everyday products. (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour)

Although Sakurajima is a source of hazard, it also offers many benefits to its residents. Its fertile volcanic soil supports the growth of unique crops, including the world’s largest radish and the smallest mandarin. It also has the highest number of hot springs (onsen) in Japan, with a total of 2,730. The mild climate and well-drained volcanic earth further enhance the region’s agricultural richness [3].

Beyond these practical benefits, many locals feel rooted to this land. Their parents and grandparents lived here, and this lifestyle has been passed down through generations. Another key reason they stay is trust – they seem to have deep confidence in their disaster risk reduction systems. And that trust is infectious. I remember when I first stepped onto Sakurajima Island, I went to ask for a tourist map while quietly battling an inner fear that the volcano might erupt at any moment. I kept trying to comfort myself by looking at the people around me – calm, relaxed, and going about their day as if nothing extraordinary was looming above us. But then a new fear would creep in: what if this is the moment of another big eruption? As I stood there wrestling with my thoughts, the woman at the desk handed me the map and said with a cheerful smile, “If you are lucky, you will see the eruption today!” I asked her if she was not afraid. Her reply stayed with me: “We have a very good early warning system. If something is about to happen, the whole island can be evacuated in a very short time, as long as we follow the instructions and calmly head towards the designated shelters on the shore, where many rescue boats will ferry us to safety. Enjoy your visit!”

How the city prepares

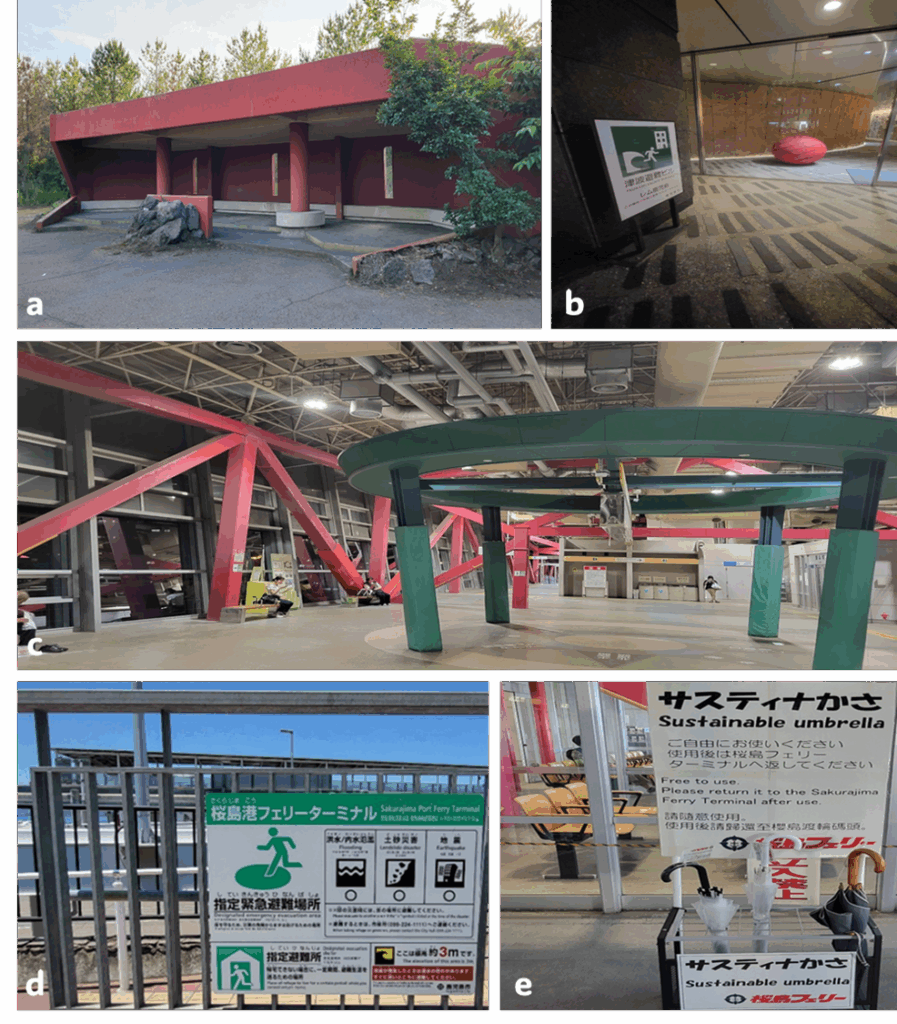

Simply walking through the city gives you a sense of preparedness, as if everyone is ready for a hazard that could occur at any moment. The existence of the volcano has shaped the lifestyle of the area. Streets are equipped with hazard guidance signs for multiple risks, including volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, floods, and tsunamis (often accompanied by English translations). There are designated volcanic shelters throughout the city, and taller buildings are equipped with rooftop areas for tsunami evacuation. On Sakurajima Island, evacuation ports have been built in preparation for a major eruption – one that could occur once in a hundred or even a thousand years. Plastic bags for collecting volcanic ash are distributed to households, and each resident is responsible for cleaning the ash around their property. Sustainable umbrellas are installed throughout the area, freely available for anyone to borrow, whether it is to shield from rain, volcanic ash, or the scorching sun.

(a) A designated evacuation shelter built to protect people from falling volcanic debris during an eruption; (b) Entrance to a tsunami shelter in a high-rise building; (c) This public terminal is equipped with bold, earthquake-resistant red steel bracing and reinforced pillars – designed to withstand seismic shocks and volcanic activity while remaining operational during emergencies; (d) An informative panel showing tsunami evacuation directions, hazard awareness zones, and shelter height (the recommended elevation for safe shelter – 3.7 meters above sea level); (e) A free umbrella-sharing service available to residents and visitors (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour)

In Kagoshima Prefecture, schoolchildren wear helmets as part of their daily routine when commuting to school. This is because when Sakurajima erupts, lapilli (volcanic ejecta), ranging from a few millimetres to several centimetres, can fall in populated areas. If children are walking or playing outdoors, these falling fragments could cause them injury. Helmets are, therefore, a daily necessity, especially for children living on Sakurajima.

Model of a typical schoolchild in Kagoshima Prefecture, equipped with a protective yellow helmet and school backpack (randoseru) as part of their daily routine. (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour from Sakurajima visitor centre)

More importantly, real-time online advice is available through the Kagoshima City Disaster Information System (Sidle et al., 2017). The Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University (Sakurajima Volcano Research Centre), has a high-tech volcanic monitoring system to ensure that residents can live safely. Seismometers, infrasound sensors, live camera footage, and ash dispersion maps, as depicted in the picture below, offer visitors a glimpse into the sophisticated monitoring systems used to track volcanic activity. Managed by the Japan Meteorological Agency, these tools aid in forecasting eruptions and assessing the direction of ash fallout, which is a vital part of Kagoshima’s disaster preparedness strategy. Last but not least, special ventilation systems have been developed to reduce indoor exposure to volcanic ash [2].

Real-time volcano monitoring at the Sakurajima Visitor Centre (Image credit: Hedieh Soltanpour from Sakurajima visitor centre)

Final words

In Kagoshima, exposure is high; there is no denying that. But the city teaches us that exposure is not destiny. With strong preparedness, awareness, and community action, vulnerability can be reduced, and risk managed. Perhaps that is the true message behind those helmets, the sustainable umbrellas, the yellow ash-collecting bags, the shelters, and the earthquake- and tsunami-resistant buildings (and countless other small acts of preparedness, seen and unseen): not fear, but a quiet, practised form of everyday resilience. As I left Kagoshima, I could not help but admire the calm determination of its residents. I wish them continued strength and safety as they live side by side with the volcano, not in fear, but with resilience.

For a visual glimpse into what I have written about, you can watch this short video about Sakurajima, which is played at the Sakurajima visitor centre for visitors.

References

[1] City Population. (n.d.). Kagoshima (Japan): Prefecture, cities and towns. Retrieved July 1, 2025, from https://www.citypopulation.de/en/japan/admin/46__kagoshima/.

[2] Deguchi, K. (1991). Development of a ventilation system against volcanic ash fall in Kagoshima. Energy and Buildings, 16(1-2), 663-671.

[3] Kagoshima Prefectural Visitors Bureau. (n.d.). Hot Spring Kingdom Kagoshima.

[4] Nakajima, M. T. E., Takahata, N., Shirai, K., Kagoshima, T., Tanaka, K., Obata, H., and Sano, Y. (2022). Monitoring the magmatic activity and volatile fluxes of an actively degassing submarine caldera in southern Japan. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 317, 106-117.

[5] Sidle, R. C., Gallina, J., & Gomi, T. (2017). The continuum of chronic to episodic natural hazards: Implications and strategies for community and landscape planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 167, 189-197.

[6] Sakurajima visitor centre.

Edited by Asimina Voskaki and Navakanesh M Batmanathan