Building the Earth in a sandbox

The Main Ethiopian Rift stretches for hundreds of kilometers through Ethiopia, a massive fracture where Africa is slowly tearing apart to birth a new ocean. However, the processes driving this continental breakup remain hidden deep beneath layers of volcanic rock and millions of years of geological history. Today, in a laboratory in the heart of the beautiful city of Florence, we can watch these same tectonic forces unfold in a box of sand, scaled down, but faithful to the real thing. This week, Conor Farrell writes about how analogue modelling allows us to understand the mechanics behind one of Earth’s most dramatic geological processes.

Almost three years ago, I was standing near the peak of Acatenango, a volcano in the Central American Volcanic Arc, observing the dramatic eruptions at Volcán de Fuego less than three kilometres away from me. For those who are less familiar with active volcanoes, standing on the edifice of a volcano like Fuego is like playing Russian roulette, except instead of bullets, there could be flows of hot gas and rocks travelling at over a hundred kilometres per hour, capable of destroying entire towns. Fuego is the most active and deadly volcano in Guatemala, with minor eruptions occurring several times an hour. Fortunately, if you watch the eruptions from the neighbouring Acatenango as we did, you can safely observe some of the most extraordinary sights on Earth. Fuego, and indeed the entire volcanic arc, is an incredible part of the world and absolutely worth seeing if you have the chance!

These days, I regularly find myself in a laboratory, staring at a box of sand. This may seem both completely unconnected to volcanoes and unremarkable in comparison, but I promise: once you understand what is happening in that box, you will realise its larger significance.

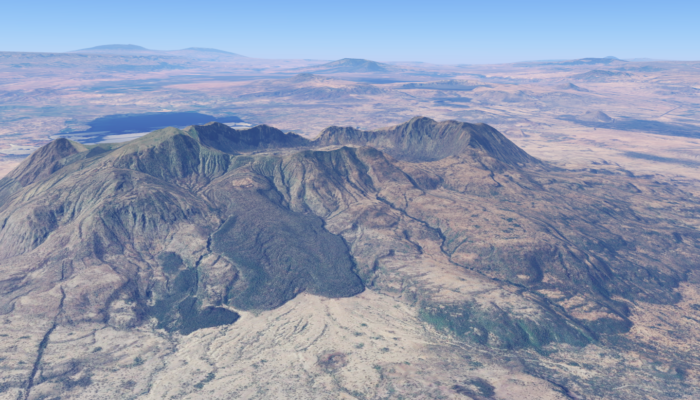

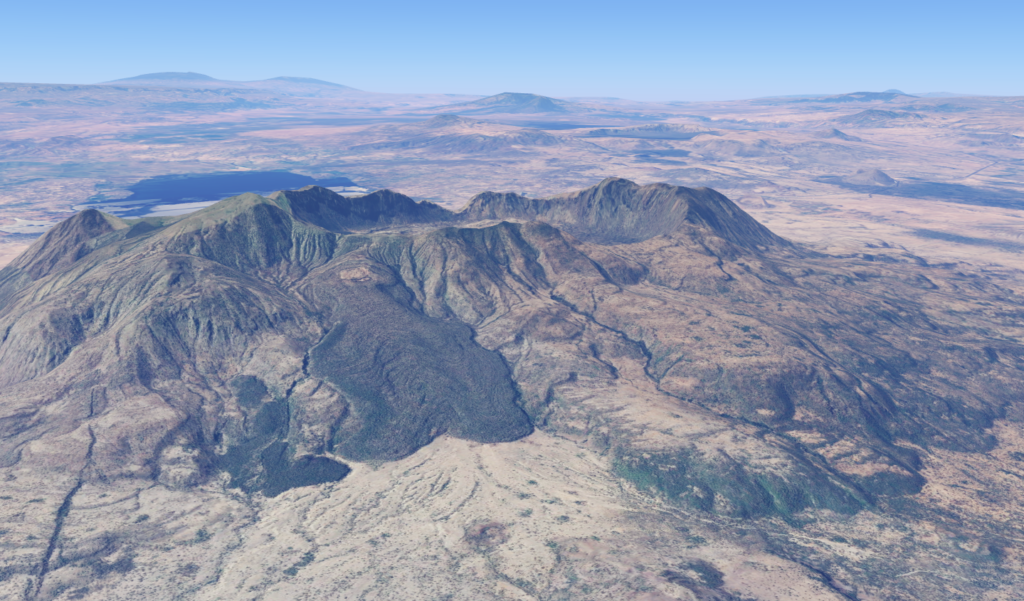

An image of Fentale Volcano in the Main Ethiopian Rift, taken from Google Earth (three times vertically exaggerated).

The East African Rift

Topography and kinematic plate boundaries (Sarah D. Stamps based on Bird 2003) of the East African Rift System.

I began my journey in analogue modelling only a year ago, when I started my PhD at the University of Florence as part of the TALENTS Marie Skłodowska-Curie doctoral network. Its goal is to train the new generation of early career researchers to better understand rifting; the process by which continents split apart to form new oceans. My project looks at probably the most famous continental rift in the world: the East African Rift (EAR). The East African Rift stretches around 6,500 km from Lebanon to Mozambique, made up of several different rifts. Much of the geological interest in the vast system is because it gives us a direct look at continental split up and the onset of ocean formation. I focus on the northern section of the East African Rift, called the Main Ethiopian Rift (MER). As the name suggests, the MER stretches the length of Ethiopia, and has been active for the past eleven million years. Today, it is a striking valley over a hundred kilometres wide at some points, with large boundary faults forming the valley margins, and many layers of lava flows covering the rift floor. Most recent volcanism in the MER has occurred at calderas (large volcanic systems) and vents spread at roughly even intervals along the central axis of the rift, for example, the recent volcanism at Fentale volcano in late 2024. The MER is of interest for both scientific and industrial reasons, with a geothermal power plant in operation at Aluto, and one being built at Tulu Moye.

The MER, like many other rifts, both continental and oceanic (e.g. Afar, Iceland, Mid-Atlantic Ridge), is segmented. There has been recent work (Farrell et al. 2025) on mapping and characterising these segments, which show some similarities to the segments of ultra-slow spreading ridges (oceanic rifts), but their structure is not fully understood. But how does one peer both back in time and inside the Earth to observe the formation of such a massive structure?

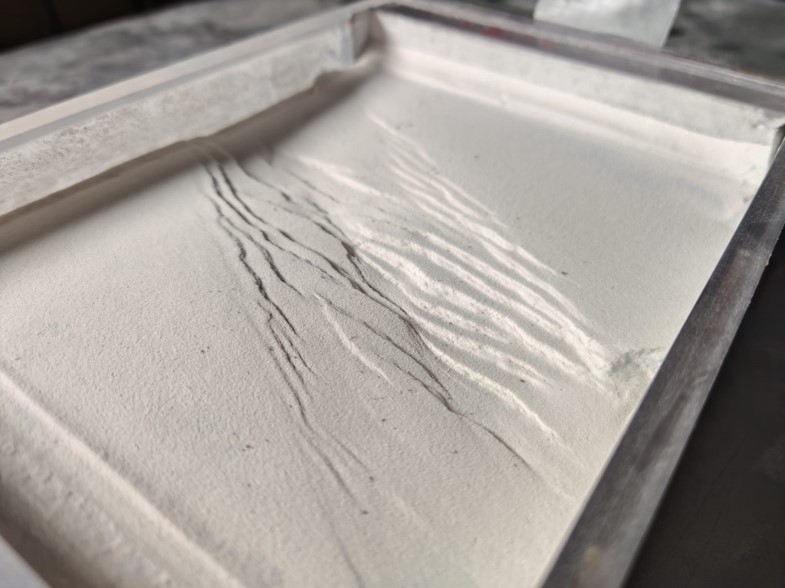

A 17 centimetre wide rift ! An image of an analogue model of the Main Ethiopian Rift from my experiments.

Analogue models

Short of a TARDIS, we can turn to analogue modelling. Thanks to the laws of physics, we can apply the principles of kinematic, geometric and dynamic equivalence to make our box of sand truly represent a continental plate. This is perhaps the most magical part of analogue modelling: by scaling the strength of the materials we use, the dimensions of our model, and the forces we apply, the same structures will develop in our model that develop on Earth! Looking down at the modelled rifts in the lab, you could imagine yourself as a satellite in orbit around the Earth, capturing images of the real thing in Ethiopia. We use these satellites to, among other things, create digital elevation models (DEMs) of the Earth’s surface. We can obtain the same elevation data from our models using simply a camera and photogrammetry. Not only can we collect quantitative data like this, but the modelling process I use works in steps. Every three millimetres, we capture photographs of the evolution of the model, meaning we record the evolution of a rift through time.

But what does this have to do with volcanoes?

Firstly, the topography of rift valley in the MER is dominated by several calderas, tens of kilometres apart and active in the past few thousand years, even as recently as two hundred years ago (as well as the 2024 eruptions at Fentale that I previously mentioned!). Secondly, these calderas are fed by magma systems, several kilometres underground, which undoubtedly affect the formation of the MER rift. We can add these analogues for these magma systems to our models and observe how it affects fault pattern evolution, which we have already begun doing!

Analogue models are not without their drawbacks, for example it is notably difficult to model magmatic intrusions, and the effect of thermal changes, as discussed in Frank Zwaan’s previous blog on analogue versus numerical models. Like all models, they approximate reality, with some necessary simplifications. I think however, that you will agree they nevertheless are a fascinating and useful insight into both the space and time of the Earth’s evolution.

References : Farrell, C., Keir, D., Corti, G., Sani, F., and Maestrelli, D.: New insights on segmentation of fault and magmatic systems in the Main Ethiopian Rift, EGU General Assembly 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 Apr–2 May 2025, EGU25-3745, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu25-3745, 2025.