Introduction

Humans have existed and lived alongside volcanoes for as long as we have been on the planet. For some, this has been beneficial and often, in fact, we can see how indigenous knowledge finds a sustainable approach living with them. However, in some cases, societies cannot cope and are overwhelmed with volcanic eruptions.

There are many examples from archaeological studies dealing with how ancient civilisations, successfully or unsuccessfully, lived with volcanoes. On one hand, for example, Pre-Colombian villages in Costa Rica were found to be the most resilient to the eruptions of Arenal volcano, managing to cope and survive with many eruptions. The villages were simple societies with egalitarian rules (where people are viewed as having equal rights and opportunities). This meant that they coped faster because everyone had the same duties and rights and were able to help each other without waiting for a ruler to do something for them. On the other hand, more complex chiefdoms in Central America struggled to cope with these events as they had a greater reliance on the built environment, competitive and sometimes hostile political environments and greater population densities [1, 2].

Since the 1500s and even further back in history, people have lived within the shadow of Mt. Merapi, in Central Java (Indonesia). Today, approximately 25M of people have not only persisted but thrived with one of the most active and dangerous volcanoes in the country, which since the 1900s, has kept producing lava dome collapses, pyroclastic density currents and extensive tephra fallout.

Villagers watching Mt Merapi eruption, Java, Indonesia. Image credit: EPA, 2010.

Whilst today well over 1 million people live with active volcanism all over the world; an “active” volcano does not necessarily mean an imminent eruption, but nonetheless, at the time of writing, 46 volcanoes are erupting around the world, with some having a greater impact on nearby societies than others.

The bad

Understandably, the most immediate costs of living with volcanoes are the potential for injuries, casualties, displacement and the destruction of the built and natural environment. Volcanic eruptions produce a wide range of hazards that may occur before, during or after an eruption. These cascading consequences make them particularly dangerous. For example, the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines had devastating impacts. During the eruption, the heavy rainfall from the passing of Typhoon Yunya generated lahars. But due to the seasonal nature of typhoons in the region, lahars were remobilised for several years afterwards. The eruption also generated a large ash plume that caused a temporary atmospheric cooling effect for at least a year after the event [3, 4].

Lava flows can bulldoze, block, bury and set fire to anything that comes in their path. Similar to lava, tephra (volcanic material from the size of nanoparticles to boulders) can block or bury. Other impacts of tephra can generate respiratory problems and injury people due to the falling of volcanic “ballistics” or projectiles, cause roof collapse, damage airplane components and suffocate vegetation.

As secondary hazards, lahars, slurry mixtures of volcanic debris and water and/or melted ice, are particularly dangerous because they can occur at any time and not necessarily associated with a volcanic eruption. Lahars can be formed by crater lakes, such as the one present at Mt. Ruapehu in New Zealand, generating “outbreak” lahars, or they can be the result of any interaction with the water table or groundwater, before, after or during an eruption. If the volcano is in a wet or tropical environment, an additional lahar trigger threat is the remobilisation of volcanic material due to heavy rains or hurricanes.

Lastly, pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) are one of the most dangerous volcanic hazards. They are extremely hot and fast flows of volcanic material, debris and gases that can be channelised down river valleys, blanketing the flanks of volcanoes and with the ability to travel across water.

There are additional “hidden” disadvantages that can change the ways people live with active volcanism. For the past 5 and a half years, I have studied how people live with La Soufrière volcano on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, one of the most active volcanoes of the Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc.

In historical times, the volcano erupted during the years of 1719, 1812, 1902-1903 and 1979, with additional geological evidence that it erupted multiple times prior to the written record. Before the colonisation of the region in the late 1400s, the island, as well as the wider region, was inhabited by the indigenous Kalinago, with a smaller population still in existence today. Archaeological evidence suggests that they purposefully had settlements away from the volcanoes of the Caribbean [5]. This is an interesting observation, as French translations of the Kalinago’s language do not specify any hazards associated with volcanism.

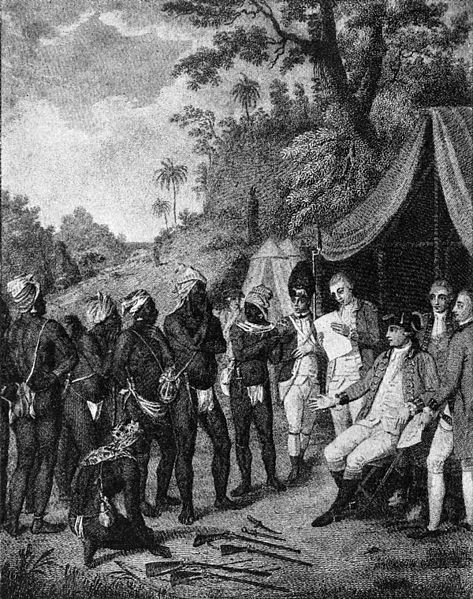

Treaty negotiations between Black Caribs and British authorities on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, 1773. Harry Johnston, 1910 – located at the New York Public Library.

With the presence of the slave trade in the Caribbean from the 1500s, runaway slaves from Barbados and St. Lucia started intermarrying with the Kalinago on Dominica, Martinique and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, becoming the Garifuna from approximately the early 1600s. This is where issues begin. The Kalinago and Garifuna on St. Vincent coexisted with La Soufrière however, due to the presence of colonists, they were pushed closer to the volcano. Upon the realisation that the fertile soil was where the volcano was, this led to the First (1769-1773) and Second Carib War (1795-1797) as colonists tried to remove the people and build sugar plantations. At the end of the Second Carib War, many Garifuna were exiled to present-day Honduras and the voice of the Kalinago was severely diminished. This led to the loss and silencing of the indigenous knowledge about La Soufrière.

As the island now consisted of European colonists and enslaved Africans who came from locations that either had no volcanism or the volcanism experienced was entirely different to La Soufrière’s, it was essentially a “new” experience for the society. Here, the indigenous knowledge would have mitigated the losses. Plantation estates were destroyed and at least 70 enslaved persons were killed in 1812.

1812 eruption of La Soufrière, painted by J.M.W. Turner.

Another hidden negative impact was during the recovery phase after the 1902-1903 eruption. This was Post-Emancipation when most former enslaved people were now farmers. During the recovery phase, racism caused barriers for black and mixed-raced persons in receiving adequate help compared to their white counterparts, which mostly came in the form of financial aid. Correspondence between the colonial government used within my research revealed that any help that was given, that black people should be “grateful” for any help they got.

“Refugee children, Kingstown, St. Vincent”. By Tempest Anderson, 1902. Used with permission from the Yorkshire Museum.

By 1979, St. Vincent was able to respond to eruptions without fatalities. This was the result of a smaller eruption compared to the 1812 and 1902 one, but also because of the clear chain of command and communication between volcanologists and local authorities that led to a prompt response from the local government, the existing social networks, and the community’s willingness to help each other. The operation was not entirely organised but the event was regarded as a “success” from a volcanic crisis, public and governmental point of view.

“The Nation” newspaper article, 27th April 1979. Photo taken by Jazmin Scarlett, 2016

Within this article, I have talked about how social aspects turned the hazard into a disaster. This is because the natural hazard processes are indeed natural, but it is the “failings” of a society’s social, economic, political and environmental systems that turn the hazard into a disaster. Essentially, it is not a disaster without people.

To be continued…

Bibliography

[1] Torrence R. and Doelman T. (2007) Chaos and selection in catastrophic environments: Willaumez Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. In: Living under the shadow: cultural impacts of volcanic eruptions. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press Inc. Pg. 42-66. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315425177/chapters/10.4324/9781315425177-8

[2] Sheets P. (2012) Responses to Explosive Volcanic Eruptions by Small to Complex Societies in Ancient Mexico and Central America. In: Cooper J. and Sheets P. (eds) Surviving Sudden Environmental Change. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. Pg. 43-65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/j.ctt1wn0rbs.7.pdf

[3] Bluth G.J.S., Doiron S.D., Schnetzler C.C., Krueger A.J. and Walter L.S. (1992) Global Tracking of the SO2 Clouds From the June 1991 Mount Pinatubo Eruptions. Geophysical Research Letters. Vol. 19 (2). Pg. 151-154. https://doi.org/10.1029/91GL02792

[4] Pierson T.C., Daag A.S., Delos Reyes P.J., Regalado T.M., Solidum R.U. and Tubianosa B.S. (1996) Flow and Deposition of Posteruption Hot Lahars on the East side of Mount Pinatubo, July-October 1991. In: Newhall C.G. and Punongbayan R.S. (eds) Fire and mud: eruptions and lahars of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pinatubo/pierson/

[5] Callaghan R. (2007) Prehistoric Settlement Patterns on St. Vincent, West Indies. Caribbean Journal of Science. Vol. 43 (1). Pg. 11-22. https://doi.org/10.18475/cjos.v43i1.a3

About the author

Jazmin Scarlett studied BSc (Hons) Geography and Natural Hazards at Coventry University and MSc Volcanology and Geological Hazards at Lancaster University, where she did a social volcanology dissertation investigating the volcanic risk perceptions of La Soufrière St. Vincent, where her family is from. She has recently passed her PhD in Earth Science at the University of Hull specialising in historical and social volcanology, titled: “Co-existing with volcanoes: the relationships between La Soufrière and the society of St. Vincent, Lesser Antilles”. Her broad research interests are human-volcano interactions, focusing on risk, vulnerability, resilience, perceptions, culture, heritage and education. She is now a Teaching Fellow in Physical Geography at Newcastle University and starting a small research project investigating the mental health impacts of professionals who communicate risk.

Post edited by: Giulia Roder, Valeria Cigala and Gabriele Amato

cable and fibre hauling services

Your blog is helpful and its so great information. Very nice post ..