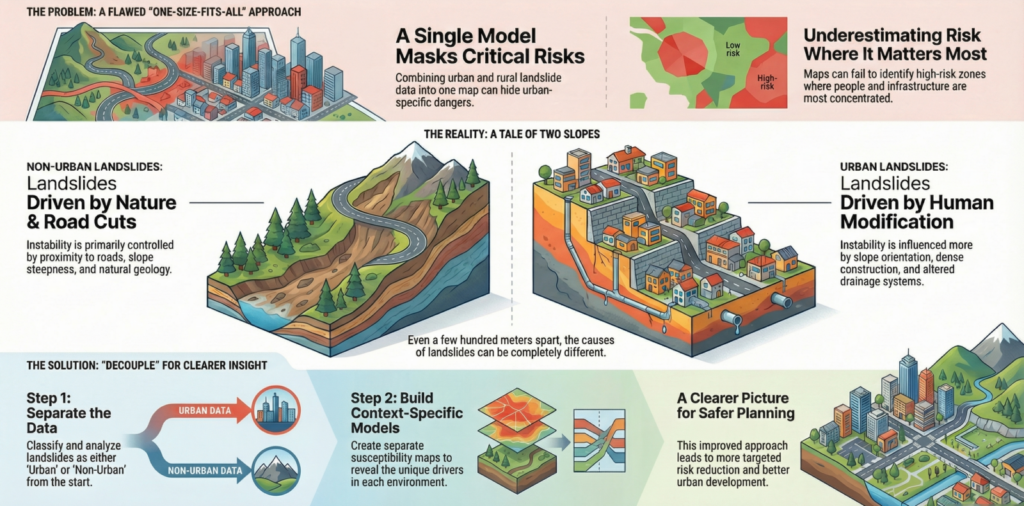

Cities are expanding faster than ever, often onto steep and unstable terrain. As urban areas grow, landslides increasingly threaten homes, roads, and critical infrastructure. To manage this risk, scientists produce landslide susceptibility maps, which estimate where landslides are most likely to occur. These maps are widely used by planners and decision-makers. But there is a quiet assumption built into many of these maps: that landslides occurring in cities and those happening in surrounding rural areas follow the same rules. Our research suggests that this assumption does not hold [1].

One landscape, two different landslide systems

In many regions, especially in developing and transitional landscapes, cities expand directly into hilly or mountainous terrain. Constantine, a rapidly growing city in north-eastern Algeria, is a clear example. Urban neighbourhoods, roads, and infrastructure are interwoven with natural slopes, agricultural land, and undeveloped areas.

Traditionally, landslide susceptibility models use a single inventory of past landslides and a single set of environmental factors to represent the whole area [2]. This approach mixes urban and non-urban landslides together, implicitly treating them as expressions of the same underlying process [1].

However, urban slopes are not simply natural slopes with buildings on top. Construction activities, road cuts, drainage modification, and increased loading all change how slopes behave. At the same time, rural slopes are still mainly shaped by geology, topography, vegetation, and rainfall. This raises a simple but important question: What happens if we treat urban and non-urban landslides as separate systems?

Conceptual framework of the study. This diagram illustrates the main idea behind the study: landslides are first separated based on land use into urban and non-urban inventories, rather than being analysed together (image credit: author)

Decoupling landslides by land use

To explore the above-mentioned question, we developed a framework that separates, or decouples, landslides based on whether they occur in urban or non-urban areas. We applied this approach in south-western Constantine, using the same terrain, the same climate, and the same background data, but two distinct landslide inventories.

Instead of asking where landslides occur in general, we asked two parallel questions:

- Where are landslides more likely to occur in urban areas?

- Where are landslides more likely to occur in non-urban areas?

This allowed us to directly compare the controlling factors of slope instability across land-use contexts.

Different drivers dominate in different settings

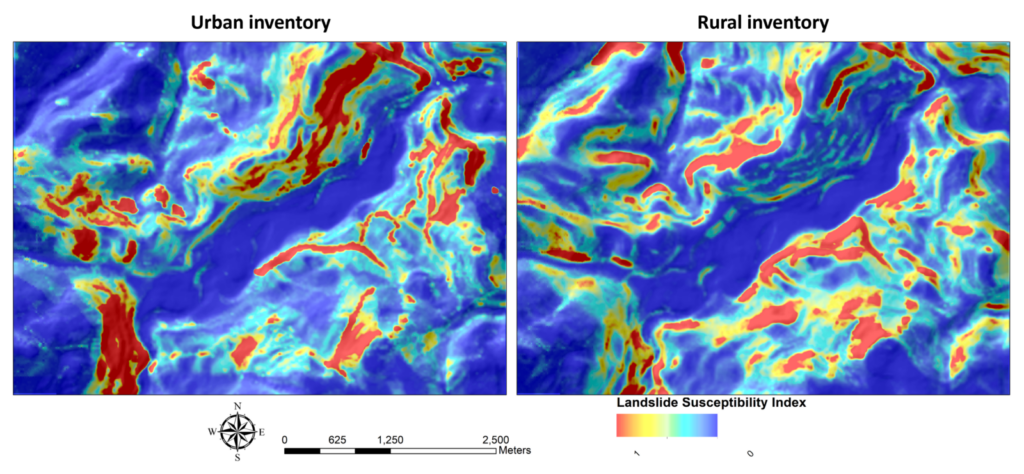

The results show a clear divergence between urban and non-urban landslides. In non-urban areas, landslide susceptibility is strongly controlled by proximity to roads. Roads in rural and peri-urban (transitional zones at the edge of cities where urban and rural land uses mix) environments often cut into slopes, alter surface runoff, and concentrate water, all of which can destabilise terrain. Slope steepness and geological conditions also play an important role, as expected in largely natural landscapes.

In contrast, urban landslides are influenced more by slope orientation, local topography, and the cumulative effects of dense construction. Drainage alteration, artificial loading, and modified surface conditions appear to reduce the relative importance of some classic natural factors, while amplifying others. In simple terms, urban landslides and rural landslides respond to different stressors, even when they occur just a few hundred metres apart.

Urban versus rural landslide susceptibility maps. Comparison of landslide susceptibility maps produced separately for urban and non-urban areas using a random forest approach. The maps show clear spatial differences in predicted landslide-prone zones, reflecting the contrasting controls on slope instability in built-up areas and surrounding rural landscapes (image credit: author)

Why mixing inventories can be misleading

When urban and non-urban landslides are combined into a single susceptibility model, the dominant signals from one environment can mask the behaviour of the other [1]. For example, strong road-related signals from rural areas may overshadow urban-specific mechanisms, leading to maps that underestimate risk within the city itself.

This matters because susceptibility maps are often used to guide land-use planning, infrastructure development, and risk mitigation strategies. A map that performs well overall may still fail in precisely the places where people and assets are most concentrated. Decoupling landslide inventories does not require new data or more complex models. It requires a conceptual shift: recognising that land use fundamentally alters slope processes.

Implications for rapidly growing cities

Many cities around the world are expanding into unstable terrain under pressure from population growth and land scarcity. In these settings, treating landslides as a single homogeneous hazard can lead to incomplete or biased risk assessments.

Our findings suggest that separating urban and non-urban landslides can:

- Improve the interpretability of susceptibility maps

- Reveal urban-specific drivers of slope instability

- Support more targeted risk reduction strategies

- Provide clearer guidance for planners and engineers

This approach is particularly relevant for cities in Mediterranean, semi-arid, and mountainous regions, where natural and human-modified slopes coexist; while the dominant drivers may vary between cities, the principle of decoupling urban and non-urban landslides is broadly applicable and transferable across settings.

Looking ahead

Landslides are not only a natural hazard; they are increasingly a product of how we build and modify the land. As cities continue to grow, hazard assessment methods must evolve to reflect this reality. Decoupling urban and non-urban landslides is a small methodological step, but it leads to a clearer understanding of how human activity reshapes slope instability and how we might better live with it.

References

[1] Matougui, Z., Daksi, Y. M., Dib, M., & Benabbas, C. (2025). Decoupling urban and non-urban landslides for susceptibility mapping in transitional landscapes: A case study from Southwestern Constantine, Algeria. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 25(11), 4629–4653. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-25-4629-2025

[2] Zhang, Junyi, Xianglong Ma, Jialan Zhang, Deliang Sun, Xinzhi Zhou, Changlin Mi, and Haijia Wen. 2023. ‘Insights into Geospatial Heterogeneity of Landslide Susceptibility Based on the SHAP-XGBoost Model.’ Journal of Environmental Management 332(January):117357. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117357.

[3] Non-Urban Landslides for Susceptibility Mapping in Transitional Landscapes : A Case Study from Southwestern.’ Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 4629–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-25-4629-2025.

Post edited by Navakanesh M Batmanathan and Hedieh Soltanpour