Before modern instruments, our only clues about past sea events came from written records and folklore. Along the eastern Adriatic coast, stories of sudden floods and “tidal waves” (locally called šćiga) have been passed down for generations. These waves, described as rapid rises and falls of the sea that could flood or empty harbours within minutes, were carved into Adriatic coastal life as rare but unforgettable events. Today, we know that many of them were meteotsunamis: tsunami-like waves triggered by very specific, localised weather conditions and amplified through a chain of resonances.

By digging through old newspapers, church chronicles, and eyewitness notes, we can turn these stories into data. It feels a bit like detective work: piecing together scattered clues to uncover real events and understand what caused them.

So how do we actually “catch” a meteotsunami? The recipe combines curiosity, persistence, and a bit of luck.

The first clue

The first clue about a meteotsunami often comes from conversations with local people or from blogs, Facebook groups, and similar sources. Two years ago, around November 2023, we noticed a post in the Facebook group “Vrboska on Hvar – Little Venice”. The post contained black and white photos of the great šćiga in Vrboska – the photos revealed that much of this small coastal town was flooded. Facebook users started remembering, “It was an event sometime in the 60s”, “I know that man standing there”, “I also remember this flood – and have photos of it”, “I think it was 1965”, “No, it was earlier…”. Curiosity took over.

One of us packed a bag and headed to the island of Hvar to track down the story in person. She met the lady who had published the photos, as well as her father, who was present when they were taken. The father was exceptionally kind and recounted everything he remembered – and it was a lot. And then bingo! A date was written on the back of the photos: 5 August 1965. Excellent! Or so we thought. When we checked newspapers from that time, nothing came up. Not a single word, even though the photos clearly showed a dramatic flood. Hm… Then we checked atmospheric reanalysis and sea-level charts from the two nearest tide gauge stations (Split and Dubrovnik). But again, a surprise – nothing in those data indicated that a strong flooding event had occurred in the middle Adriatic.

What now? Wait, there was another person posting in the Facebook group who said he also had photos of the event and thought it happened in 1963, when he was just a kid. Perhaps we could find him! Perhaps his photos also had a date on the back. We found him (he was quite surprised!) and he found his photos. This time, 1963 was written as the year, but with no exact date. Once again, we had to examine sea-level charts to identify suspicious dates. We extracted five or six main suspects and returned to the newspaper archives. Fortunately, newspapers were rather short at that time – eight pages at most, unless there was a special occasion. Finally, we found a very brief article stating that on 21 August 1963, an unheard-of flood occurred on Hvar Island. That was it, we concluded! Now we had framed our event.

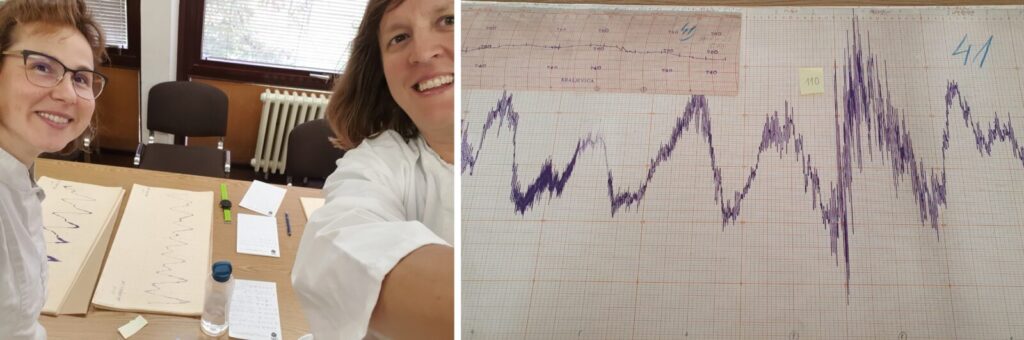

Left: Iva and Jadranka inspecting historical sea-level charts from the tide-gauge station in Bakar – the oldest in Croatia, recording for almost a century. Right: Sea-level records from October 1932 showing a strong candidate for a meteotsunami on 8 October, with a wave height exceeding 1 m. (Wow – those old-timers really made our job easier by neatly archiving air-pressure data from the nearest meteorological station in Kraljevica, which we didn’t even know existed back then!) (image credit: authors)

Searching the archives

Generally, whenever a possible date or location pops up, we head straight to the archives and libraries to track down more clues. Key details – the day, the place, and sometimes even descriptions hinting at wave periods or heights – often hide in tiny text-only reports (older newspapers relied far more on words than photographs). Sometimes these hints jump out from dramatic headlines like “Tidal Wave Attacked Stari Grad”, “Raging Sea in Vela Luka”, or “Unexplained Natural Phenomenon”. Other times, they hide in far more vivid lines – like the unforgettable “Housewives were catching fish with aprons”. Hours spent buried in archives and old newspapers may sound dull, but they’re often anything but! While searching for meteotsunamis, you end up tripping over all sorts of oddities – from hilarious ads to bizarre articles – each one a powerful witness to its era and a reminder of the unchanging quirks of human nature.

For a moment, we can slip into the shoes of a reader in the early 20th century, when all news came through the daily papers. On 25 November 1922, Obzor reported that, for the first time, women were permitted to participate in court proceedings in Zagreb as lawyers and advocates. Judgeship was still closed to them, but the first step had been taken – a glimpse of slow yet steady social change. If you think dating apps are a modern thing, think again. Old newspapers were just the same platform in a different format: full of marriage and courtship ads, offers to correspond, and messages to suitors. In Jutarnji list (1933), a woman under the pseudonym “Blue Flower” left a message for her chosen one “Is everything forgotten? I don’t believe that! Why don’t you write back?” Ghosting existed even then – via print! In Obzor (1906), there was a regular “Lost & Found” section informing readers what had been discovered in Zagreb. On 11 January 1906, the list of found items included coins, a silver earring (one!), a shoe-upper leather piece (one!), hemp yarn, candles, socks, keys – and even a goose, a stork, and dogs. From the smallest odds and ends to living creatures. And sometimes, we stumbled upon stories that made our blood run cold. On 10 September 1932, Obzor reported a horrific crime on the island of Hvar, told in a tone worthy of a Scandinavian thriller – proof that fascination with dark stories is nothing new.

But let’s get back to meteotsunamis!

Left: A map of historical meteotsunamis in the Adriatic, showing events with wave heights of 2 m or more (based on the Catalogue of the Adriatic Meteotsunamis). Right: A report from 24 August 2007 (newspapers Večernji list) describing a meteotsunami in Široka Bay on the island of Ist (22 August 2007). According to the article, the wave reached about 2 m in height and had a period of less than 10 minutes. The author also notes that older locals recall a similar event from 1984 (image credit: authors).

Checking the cause

Once we have a date, we verify in the earthquake catalogue that the event wasn’t triggered by an earthquake. This step is crucial because in the past, some Adriatic tsunamis were mistaken for meteotsunamis, and vice versa.

Analysing available data

If the event passes the first check, we move to further data analysis. This means looking at atmospheric pressure measurements, synoptic charts, reanalysis fields or tide-gauge records. Because meteotsunamis are so localised, direct measurements are often missing, but nearby data can still provide important hints.

By following these steps, scattered anecdotes turn into a structured Catalogue of the Adriatic Meteotsunamis [1]. This catalogue is alive – and keeps growing as new stories and sources are uncovered. In this way, old memories become new science.

Why does this matter today?

Hunting historical meteotsunamis is not just an academic curiosity – it has a very practical value. Once an event is identified, it can be reconstructed with today’s tools. Weather maps and measurements can be re-examined, and ocean-atmosphere hydrodynamical models can be run. If a simulation produces an ocean wave similar to the one described in the reports, our confidence grows that it really was a meteotsunami. And the Catalogue of the Adriatic Meteotsunamis, combined with numerical modelling reconstructions, reveals where the Adriatic Sea meteotsunamis tend to strike most often (e.g., Vela Luka, Stari Grad, Mali Lošinj) and under which conditions. Knowing these hotspots helps focus monitoring and warning systems where they are needed the most.

A network of microbarographs and tide gauges was installed in the middle Adriatic by the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries in Split as the first step in setting up an operational meteotsunami monitoring and warning system [2]. The system was envisioned to be based on a combination of real-time measurements and atmospheric and ocean modelling. However, the second part, forecasting meteotsunamis with hydrodynamical models, proved to be extremely challenging, mostly due to the fact that atmospheric disturbances that trigger meteotsunamis are often too small to be realistically reproduced and forecasted by present-day models. As a way forward, new approaches are being explored: we are currently developing deep learning models trained on ERA5 reanalysis and high-frequency sea-level measurements to predict meteotsunamis, with promising first results [3].

Together, historical records, new monitoring systems, and deep learning may bring us closer to reliable meteotsunami forecasts.

P.S. We invite anyone with useful information that could lead to the identification of an Adriatic meteotsunami to contact us immediately. And remember – if you post photos of suspicious sea activity on social media, we’re watching!

References

-

- Šepić, J. and Orlić, M. (2025): Catalogue of the Adriatic Meteotsunamis, https://projekti.pmfst.unist.hr/floods/meteotsunamis/, accessed 19 Sep 2025

- Šepić, J. and Vilibić, I. (2011): The development and implementation of a real-time meteotsunami warning network for the Adriatic Sea. Natural Hazards and Earth System Science, 11, 83-91, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-11-83-2011

- Međugorac, I. and Ličer, M. (2024): HF-SCANNER: High frequency sea-level oscillations modeling in the Mediterranean using machine learning, https://smash.ung.si/fellows//, accessed 19 Sep 2025

Post edited by Asimina Voskaki and Navakanesh M Batmanathan

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

Thanks for the blog post Thanks Again. Really Great

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

The topic is good and valuable, and I benefited from it. Thank you.

Faculté des Lettres et Langues

his was a great read—very helpful