Ultraperipheral European departments like Mayotte are developing regions, often disproportionately exposed to natural hazards and struggling to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

The eye of cyclone Chido, the most violent storm to hit Mayotte island in 90 years, engulfed the French Department on the 14th of December 2024. The extensive destruction and massive loss of life ranks this event as the largest natural disaster in France since the 1902 Mt. Pelé eruption in another Ultraperipheral Department, Martinique.

The United Nations 2015-2030 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) promotes the adoption of people-centred approaches, such as citizen science, to engage populations in disaster risk mitigation and improve awareness and preparedness. Better involvement of vulnerable communities in risk management is critical for the success of DRR policies.

Scientists can play a pivotal role in fostering dialogue between authorities and the population, thus moving towards more inclusive and effective policies for multi-hazard risk management. Scientists provide comprehensive risk assessments and can contribute to developing inclusive management plans. They can thus contribute to improving the effectiveness of the government’s communication on action plans to reduce natural disasters and facilitate marginalised communities’ involvement in decision-making.

Mayotte Island and its socio-demographic context

Mayotte archipelago is formed by two main islands, the main one on the west, Grande Terre (363 km2) and a smaller one on the east, Petite Terre (11 km2) (Fig. 2). Mayotte is one of the four islands of the Comoros archipelago in the Indian Ocean, running between Madagascar and Mozambique.

Mayotte Island is a French overseas Department located in the northern part of the Mozambique Channel, and it is one of the nine European Ultraperipheral Regions which form the so-called “jewels of the EU’s crown”.

The island has been a French department since 2011. It has a low level of economic development, and its population is very young, with >70% of inhabitants living below the poverty line and 25% having no formal settlements [1]. A large part of the population has no qualifying diploma, and a significant percentage is illiterate.

Only 63% of the population older than 14 years were French speakers in 2007. The most common language is a Sabaki Bantu language, the Shimaore. The island is located at a migratory crossroad with neighbouring countries (Union of the Comoros, Madagascar), with much lower economic development and social protection levels. It is estimated that 40% of Mayotte’s inhabitants are foreigners.

As an ultra-peripheral European region, Mayotte benefits from Community financing and European funds for territorial cooperation. The exceptional circumstances related to the status of ultra-peripheral areas, recognised by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, have specific allocations to partly compensate for the additional costs due to its insularity.

Scientific assessment of natural hazards and support for risk management in recent years

Mayotte Island is exposed to multiple natural hazards, such as floods, landslides, cyclones, earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions.

The 2018 seismo-volcanic crisis linked to the birth of the submarine Fani Maoré volcanic edifice (the largest effusive eruption since centuries, building a 800 m-high cone of basaltic lava located 50 km east of Mayotte at a depth of 3.5 km bsl) has been the catalyst for the integration of new elements into the risk prevention strategy and the improvement of the anticipation of crisis situations.

The island was shaken by a strong seismic crisis in 2018 linked to the birth of the new submarine volcano, which generated intense anxiety in the population. Before 2018, when tens of earthquakes/month with a magnitude up to M 5.9 occurred, Mayotte was considered an area with moderate seismic activity and the last felt earthquake was in 1993. The eruption was followed by progressive subsidence of the island and increased gas emissions associated with draining a huge, deep magma reservoir. The 2018 event caused limited building damage but had a strong societal impact.

Fig.1: Interreg project on the sources of seismic and volcanic activity on the Comoros archipelago that permitted intense exchanges between French and Comorian institutions and authorities (image credit: author)

Seismo-volcanic activity is monitored in real time by a multidisciplinary French consortium (REVOSIMA). Scientists, in close collaboration with national and local authorities, have played a critical role in all steps of the risk chain, from monitoring to the dissemination of information (including monthly multi-lingual reports) on the eruptive events and their aftermath (a daily average of 10 weak earthquakes is still recorded today) to the organisation of evacuation exercises. Citizen science has been successfully tested to develop participative seismological monitoring of the Mayotte volcanic crisis.

Research on tsunami hazard has produced significant results relevant to building effective policies in a multi-hazard context. These studies have, for instance, quantified the proportion of buildings and roads potentially affected by tsunami events, modelled a set of scenarios and thus revealed potential organisational vulnerabilities. All these collaborative efforts have significantly contributed to improving the risk awareness and preparedness of a population not accustomed to frequent earthquakes before.

That “network approach” of DRR is also currently addressed within the “Ansanm Nou Lé Paré” initiative on another French Ultraperipheral territory in the Indian Ocean: La Réunion island. This collaborative initiative was inspired by Quebec’s Rohcmum, promoted by the United Nations Disaster Risk Reduction and applied by the French Association for Disaster Risk Reduction (Ansanm nou lé paré “Together we are prepared” – AFPCNT) in parallel to research dealing with disaster management coordination ethics.

Close collaboration between scientists and professionals in disaster prevention and management has contributed to the deployment at the scale of the Indian Ocean of the Red Cross program “Pare pas pare”, which educates over 30.000 children per year and has significantly increased awareness of natural hazards and risk prevention and mitigation procedures at the regional scale.

These initiatives are just some recent examples of how to strengthen disaster risk reduction culture among various stakeholders: authorities, specialists, community organisations, and citizens learn from each other (micro) locally while addressing together the challenges of disaster risk prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. They could, in turn, inspire other similar initiatives around the world based on an interdisciplinary science (social capital, emergent phenomena, disaster management, ethics) promoted and applied by DRR-oriented scientists and international cooperation.

Chido cyclone, December 2024

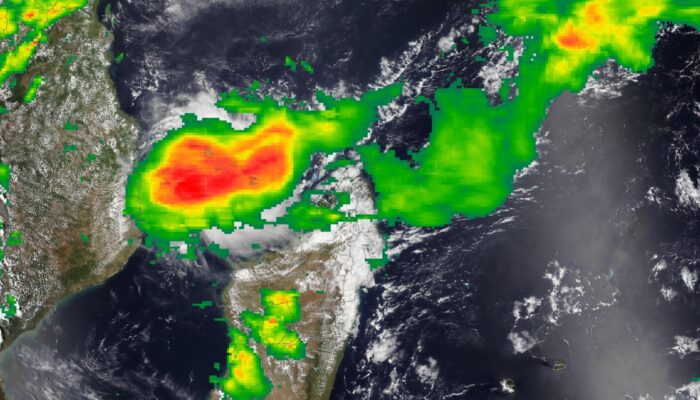

The eye of the Chido cyclone, the most violent storm to hit Mayotte in 90 years, engulfed the island on the 14th of December 2024. Maximum wind speeds of more than 200 km per hour were recorded, and these were associated with extreme rainfall and huge sea waves. Chido took an unusual track as it skirted the large Madagascar island and impacted Mayotte as an intense tropical cyclone. The track continued over Comoros and Mozambique on the 15th of December before weakening. Accurate and timely warnings have been issued by Météo-France since Friday, the 13th of December. The alert was upgraded to the rarely used violet level on Saturday 14th.

Severe loss of lives is feared, and critical infrastructures (e.g. hospital), transport (e.g. airport), and energy networks have been severely damaged. Public buildings like schools have been either damaged or used to shelter the population. The lack of experience with extreme tropical cyclones, the cyclone trajectory, the high number of poorly constructed informal housing, the challenges to transfer alert in a complex multi-lingual society, and the reluctance of some to comply with the request to move to shelters have dramatically amplified the impact of the cyclone.

A massive emergency and relief operation was quickly mobilised by local, regional (La Réunion) and national authorities as preliminary estimations suggest that hundreds of people may have lost their lives. French President Emmanuel Macron declared national mourning on the 23rd of December.

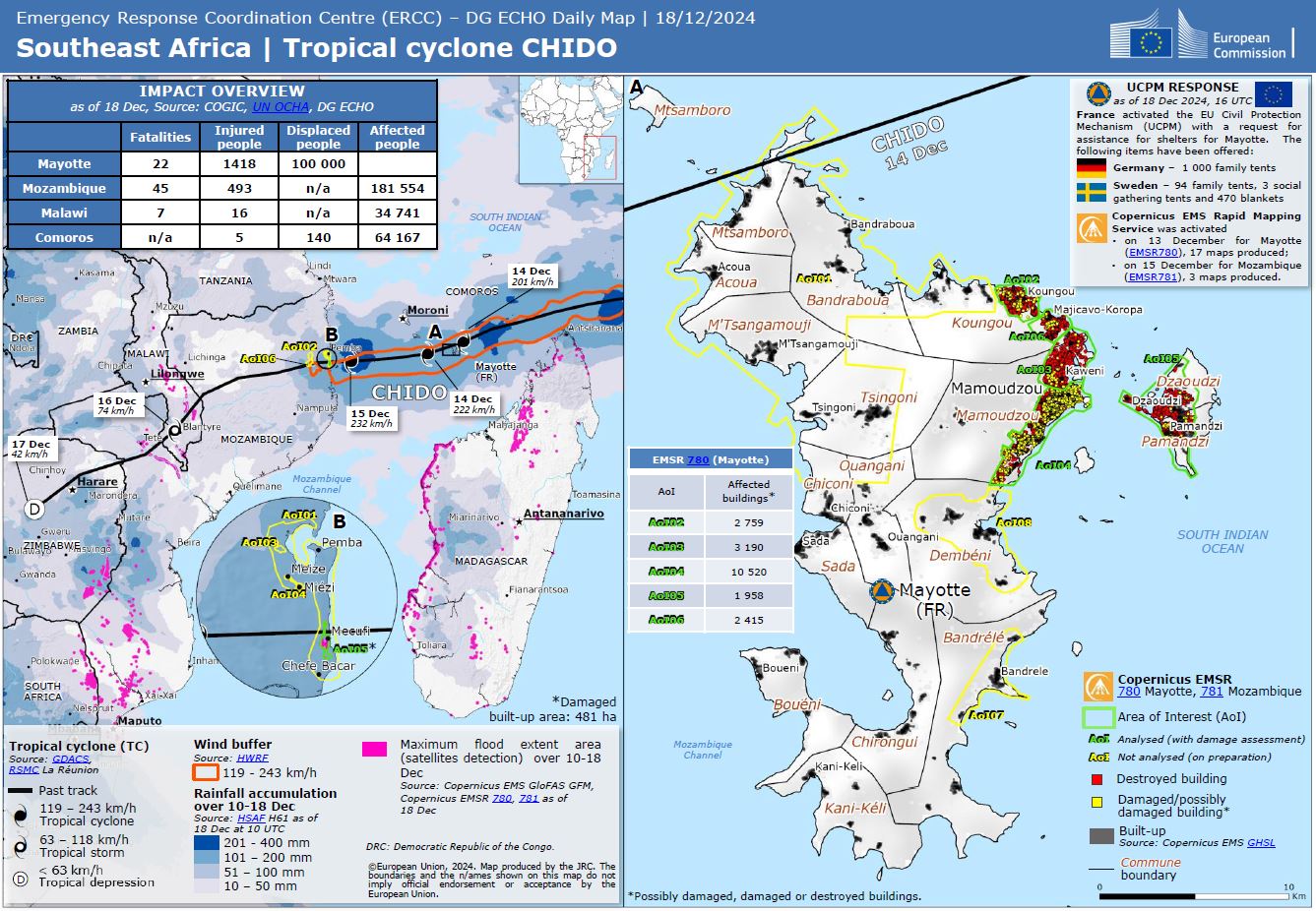

Copernicus EMS Rapid Mapping Service was activated, which permitted a rapid quantification of the extension of the destroyed and damaged buildings, notably on the north-east side of the main island (Grande Terre) and on the closely located Petite Terre, where the only airport of the island is located (Fig. 2). France activated the EU Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM) with a request for assistance for shelters for Mayotte.

Fig. 2: Tropical Cyclone Chido (image credit: European Commission)

Recommendations and reflections

The report of the Midterm Review of the Implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (pg 36) states, “Many countries identified public trust and public engagement during crises as fundamental for ensuring that questions of social inclusion are included in addressing risk. While interpersonal trust and trust in crisis management authorities is generally reported as stronger in high-income countries, increasing income disparity, increased levels of violence, and the marginalisation of vulnerable communities are compromising national efforts on social cohesion and an all-of-society approach to an integrated understanding of risk and subsequent action.”

Local and national authorities are in charge of implementing the effectiveness of precautionary and preventive principles through administrative decisions and then informing the populations at risk about the nature and evolution of a threat and the measures intended to reduce and manage it. Scientists play a key role in the “risk chain” as providers of data and alerts and in shaping the bridge between authorities, stakeholders and the population to share and understand risk-relevant scientific information. As trusted sources, scientists represent a font of credible information and can influence public decisions. As shown in many studies, scientists are often more trusted than authorities. In addition to this profile, scientists can play a key role in the decision-making process, helping the administration to operate appropriately.

Scientists and risk prevention and management professionals can contribute to building trust between authorities, stakeholders and the population, and they can foster dialogue between all parties by promoting stronger interactions in projects involving vulnerable populations and by supporting the development of citizen science and implementing forms of “shared administration”.

Moreover, they can facilitate deploying an integrated multi-hazard approach for risk reduction by opening exchanges and data access and facilitating the transfer of results obtained in a specific field (e.g. tsunamis) to other fields (e.g. cyclones). In the field of natural hazard and risk studies, researchers should systematically integrate questions of social inclusion in addressing risk prevention and disaster management.

Finally, European funding schemes and institutions can play a significant role by promoting projects, actions and policies to identify and remove the causes of distrust and facilitate population participation in policy-making processes.

References

Post was edited by Asimina Voskaki