The climate on our home planet is changing, and the effects of this change affect all of us at different levels starting from an enhancement of extreme weather events, a severe natural hazard. Climate change has several drivers, which in turn have complex interactions. Thus, it should not surprise us if climate science is a complex and interdisciplinary discipline with numerous players and great public interest. We could see it as a puzzle with hundreds, possibly thousands of pieces. To explore some of the complexity of this discipline, I have the pleasure to interview Dr Jakob Zscheischler, NH Division Outstanding Early Career Scientist (ECS) Award candidate who won one of the EGU 2022 Arne Richter Awards. These awards recognise the scientific achievements of Early Career Scientists obtained in any field of geosciences and are granted every year to four of the Division Outstanding ECS winners.

Dr Jakob Zscheischler

Before we dig into the interview, you need to know that Jakob has a background in mathematics, biogeochemistry, and climate science and pursued his PhD (2014) at two Max Planck Institutes, the one for Biogeochemistry in Jena and the one for Intelligent Systems in Tübingen, Germany. Jakob currently works on compound weather and climate events as Group Leader at the Department of Computational Hydrosystems of the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ in Leipzig, Germany.

Let me start by saying congratulations on your award, Jakob! I usually work with volcanoes, and when I first read about your research topic, I could only understand it broadly and wanted to delve more into this topic. So, I was like, what does work on compound weather and climate events actually mean?

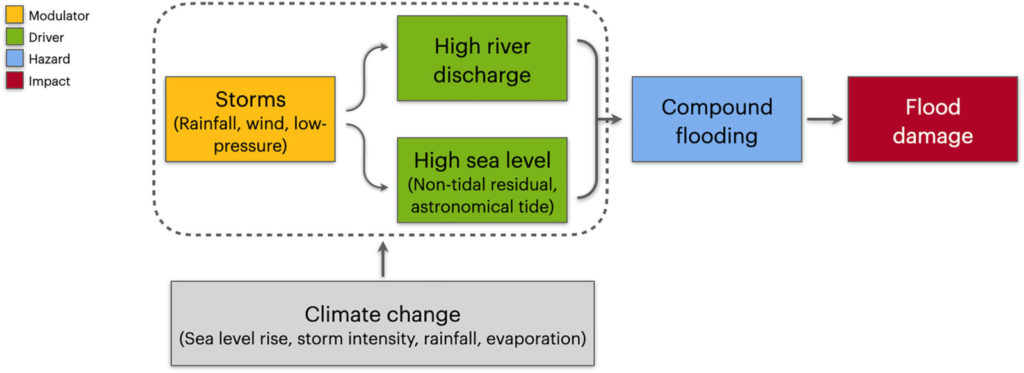

Thank you! The notion of compound weather and climate events has emerged from the insight that many climate-related impacts are caused by multiple compounding weather and climate drivers. For instance, forest mortality is associated with concurrent storm surges and heavy rainfall. You can see an example in the illustration from our recent paper on “Guidelines for Studying Diverse Types of Compound Weather and Climate Events”[1] below (Figure 1). In compound event research, we try to understand which drivers occur together to cause impacts, model their dependence, assess whether climate models represent these relationships well, and make projections. Overall, the goal is to better estimate and project climate-related risks. After our Perspective paper [2] introduced the concept four years ago to a broader audience, the topic gained a lot of momentum. We published a first review [3] just two years later, in 2020. We proposed four types of “compounding”: preconditioned events, multivariate events, and temporally and spatially compounding events. Compound events are also prominently featured in the most recent IPCC report of Working Group 1.

Figure 1: Physical elements of compound coastal flooding damages caused by the extreme water level due to compounding flood drivers [1].

Why did you choose to study and work in this field of research in particular? What do you really like about it?

I like the extremely interdisciplinary environment, combining knowledge from traditional climate modelling with climate impact research and advanced statistical approaches. It is a very new and emerging topic, which is always exciting, and it links well with my previous experience, namely mathematics (undergrad), impact research (PhD) and climate science (postdoc).

Were there any setbacks in your research so far? If yes, how did you handle them?

At the end of my PhD, I wasn’t sure if I really wanted to stay in science, and at the beginning of my postdoc at ETH, I was still unsure which direction to explore. I guess one of the main reasons was that I felt if I stayed in science, I wanted to work on something where I could really make a difference. I’m not an experimentalist and not a model developer but mostly do data analysis, which is a skill that can be learned relatively easily and doesn’t create anything really new (in contrast to collecting actual data or building a process-based model), so I felt I didn’t belong to any of the more traditional disciplines. At some point, I had a long chat with my postdoc adviser Sonia Seneviratne, and we agreed that I would work on compound events, a new topic that was an ideal fit for my background and skills. Since then, the topic has developed a lot, and now I feel quite “at home” with it.

Finally, is there something you’d like to see happening at the interface between science and policymaking related to climate science and climate change that hasn’t happened yet?

Well, I guess a lot can be said here. I’m carefully optimistic as I have the impression the youth movement in recent years has achieved more than climate science in decades in terms of influencing policymaking. We see courts ruling in favour of climate activists, something that was unthinkable a few years ago. Of course, all this would not have been possible without the continuing efforts of climate scientists and institutions such as the IPCC to assess current knowledge and inform the public. So maybe we’re at a tipping point. On the other hand, we still see many governments being afraid of making bold decisions that would leave traditional pathways and secure a habitable planet for future generations. Doing something to slow down climate change is still framed as being very expensive, even though we scientists are convinced that doing nothing is much more expensive. Maybe that’s an angle that we can focus on more.

If you are interested in discovering more about Jakob’s research, don’t miss his talk during the EGU General Assembly 2022.

References

[1] Bevacqua, E., De Michele, C., Manning, C., Couasnon, A., Ribeiro, A. F. S., Ramos, A. M., et al. (2021). Guidelines for studying diverse types of compound weather and climate events. Earth’s Future, 9, e2021EF002340. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002340

[2] Zscheischler, J., Westra, S., van den Hurk, B.J.J.M. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nature Clim Change 8, 469–477 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0156-3

[3] Zscheischler, J., Martius, O., Westra, S. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1, 333–347 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0060-z

Post edited by Paulo Hader and Shreya Arora.