Have you ever wondered what common thing connects fault surfaces and their characteristics with your… squeezy sneakers on a wet surface or the required frequent change of your car tyres? Well, the answer is simple. The fundamental principles of stress and friction can significantly cause this behaviour in our everyday lives. However, these two factors can also be responsible for the slip behaviour of fault systems in terms of seismogenesis. In this week’s blog, Geophysicist Dr. Sofia Michail will delve into how these complex fault systems and their characteristics work in the macro and micro-world in order to better understand these processes.

Sofia Michail is a geophysicist by training with a doctorate from ETH Zurich and a Master’s degree in Applied Geophysics from the IDEA League consortium (ETH Zurich, TU Delft, RWTH Aachen). You can find her on LinkedIn under her name or around in Zurich.

Have you ever wondered why your sneakers make noise when they’re wet and you walk on a hard surface or why the sneakers in basketball games are so hmm… squeezy? Or why are the tyres on your car not smooth and need to be replaced regularly? Or maybe you have slipped on the tiles around the pool when you went out of it?

Maybe, maybe not. All of the above examples are things that happen every day and have some things in common: well, they can potentially create an unpleasant situation for you or those around you. It’s hard to imagine how enjoyable slipping on a wet floor after a long swim can be, unless you’re one of your teammates who probably had the time of their lives watching you fall. Most importantly, these are all real-life situations that demonstrate some of the underlying principles of contact mechanics and friction. But how is this relevant to faults and, subsequently, earthquakes?

The role of fault surface characteristics

Well, first let’s take a step back. Most of us associate faults with earthquakes. We know that they occur at different scales and are caused by either the same or probably quite different processes. In Earth Sciences, we know that faults are very complex systems, spanning different volumes and scales. Similarly, fault characteristics such as roughness, can be observed at various scales, ranging from metres to nanometres. Conversely, in seismology and fault mechanics, trying to shed more light on the seismogenesis process, there has been a big focus on fault characteristics, especially those of the fault surfaces. The characteristics of fault surfaces and how they interact seem to play a substantial role in earthquake activity.

As with the previous examples, this raises the question of how we can study the processes connected with faults and fault surface characteristics which affect seismogenesis. How closely or remotely do we need to look? The actual question of the title of this article arises: How close is close enough?

Multiscale fault roughness and seismic slip

In order to begin to answer this, it is necessary to consider that fault surfaces within a fault zone may appear smooth from a distance, but are far from smooth when examined more closely. They can be described as rough and self-affine, the latter a term coming from fractal geometry in mathematics, though at the mesoscopic scale they appear almost polished (Power et al., 1988; Power & Tullis, 1991). The interaction of such surface features results in only partial contact; roughness dictates which small areas, called in contact mechanics asperities, carry most of the load.

This is where practically the contact of the surface takes place. These asperities concentrate normal stress, meaning that roughness and the distribution of asperities influence many aspects of the slip behaviour of faults. Research has indicated a correlation between these elements and stress concentrations, changes in friction, and the initiation or arrest of seismic slip (Ben-Zion and Sammis, 2003; Brodsky et al., 2011; Morad et al., 2022; Sagy and Lyakhovsky, 2019; Scholz, 2003).

Roughness, however, is a multiscale property; it spans the earthquakes on different scales. It also evolves with accumulating slip due to abrasive and adhesive wear. This is similar to what happens to your car tyres when you drive. The road and your tyres are both rough, and it is this roughness that gives them a good grip. Friction and the forces applied between the surface of the tyre and the road result in material being removed or transferred from both surfaces. Abrasive wear results in smoother surfaces, which is when you need to replace your tyres (or when your mechanic advises you to)!

The same applies to faults (without you needing to replace them) and affects the seismogenesis process. This evolution is visible in both natural and experimental faults: striations, grooves and fine-grained material illustrate the ongoing process of wear (Biegel & Sammis, 2004; Brodsky et al., 2016; Dascher-Cousineau et al., 2018; Kirkpatrick & Brodsky, 2014; Sagy et al., 2007). More specifically, laboratory studies in recent years have extensively explored the effect of roughness on friction, but understanding how exactly roughness evolves with slip, and how the structures that develop feed back into frictional behaviour, remains challenging (Siman-Tov et al., 2013; Siman-Tov et al., 2017).

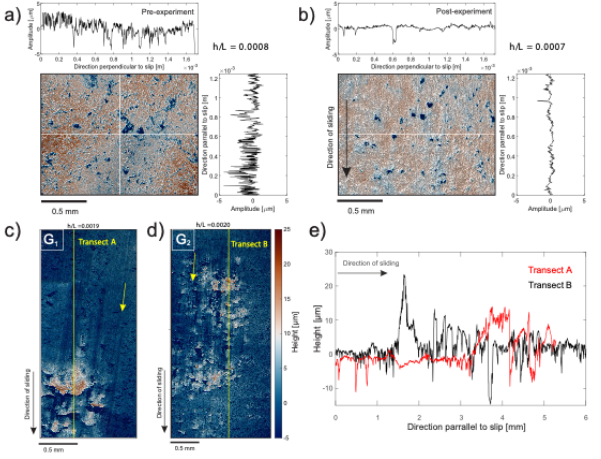

In their paper, Michail, Selvadurai, Rast et al. (2025) present and analyse a prime example of this phenomenon. Through an experimental setup, they demonstrated that laboratory-prepared fault surfaces are rough at various scales, ranging from centimetres to nanometres. While their fault surfaces were rough, this was not in the conventional sense. Specifically, they appeared very smooth to the touch. However, when examined closely at the centimetre scale, their rough geometry was revealed. This roughness (or rather, waviness) resulted in the fault being curved, with contact occurring mainly at its central asperity. Further examination with a white light interferometer, an imaging technique used to map surface height, revealed them to be even rougher at the nanometre–micrometre scale, when you look closer.

Image 1: Optical profilometry images of the central asperity before (a) and after (b) the experiment, showing height profiles parallel and perpendicular to slip. Panels (c) and (d) show scans from two gouge regions (G1 and G2), where striations in the sliding direction are visible. (e) The height distribution of the two transects parallel to the slip direction in the gouge regions G1 and G2 is shown for reference. Retrieved from Michail et al., 2025.

Stick-Slip and Fault Surface Evolution

The central asperity initially accommodated the stress while the fault was loaded, creating conditions similar to those in nature and controlling seismogenesis. A stick-slip occurred, a phenomenon equivalent to a mini-earthquake. Similarly to the noise you hear from basketball shoes on a court, the stick-slip phenomenon lives up to its name.

The surfaces (fault or sneakers) stick, and a sudden release of energy occurs due to rapid slip, which is often accompanied by a sound similar to that heard at a basketball court. The stick-slip and the cumulative slip associated with it (i.e., imagine your tyres moving) resulted in wear and material transfer.

However, it also resulted in the smoothing of the main area of contact, while new asperities appeared on other parts of the fault due to wear. All of this is fundamental to how stress and strain are accommodated at the fault, and most importantly, whether or not a second event will occur, i.e., another mini earthquake as their subsequent loading shown at their experiment.

But how can we observe all these phenomena? We observed them close up and from a distance, both in a laboratory and in the nanoworld. We also used various methods, combining traditional techniques with new technologies. One example is distributed strain sensing with fibre optic cables (a topic for another article). But why did we look so closely? Because faults, their surface characteristics and seismogenesis are complex.

What is clear is that improved observations of how roughness and fault surface characteristics change, especially with new technologies, will help us to better understand the fundamental processes behind virtually all natural fault systems. You can think of this when you are driving or on your next run in the rain!

References Amir Sagy, Emily E. Brodsky, Gary J. Axen; Evolution of fault-surface roughness with slip. Geology 2007;; 35 (3): 283–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G23235A.1 Amir Sagy, & Lyakhovsky, Vladimir. (2019). Stress patterns and failure around rough interlocked fault surface. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124, 7138–7154. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB017006 Ben-Zion, Yehuda, Sammis, Charles. Characterization of Fault Zones. Pure appl. geophys. 160, 677–715 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00012554 Dascher-Cousineau, K., Kirkpatrick, J. D., & Cooke, M. L. (2018). Smoothing of fault slip surfaces by scale-invariant wear. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 123, 7913–7930. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB015638 Doron Morad, Amir Sagy, Yuval Tal, Yossef H. Hatzor, Fault roughness controls sliding instability, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 579, 2022, 117365, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117365 Emily E. Brodsky, Jacquelyn J. Gilchrist, Amir Sagy, Cristiano Collettini, Faults smooth gradually as a function of slip, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 302, Issues 1–2, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.12.010 Emily E. Brodsky, James D. Kirkpatrick, Thibault Candela; Constraints from fault roughness on the scale-dependent strength of rocks. Geology 2016;; 44 (1): 19–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G37206.1 James D. Kirkpatrick, Emily E. Brodsky, Slickenline orientations as a record of fault rock rheology,Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 408, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.09.040 Jackson J. SCHOLZ, C. H. 2002. The Mechanics of Earthquakes and Faulting, 2nd ed. xxiv + 471 pp. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. Price £90.00, US $130.00 (hard covers); £32.95, US $48.00 (paperback). ISBN 0 521 65223 5; 0 521 65540 4 (pb). Geological Magazine. 2003;140(1):95-98. doi:10.1017/S0016756803227564 Sofia Michail, Paul A.Selvadurai, Markus Rast, Antonio F. Salazar Vásquez, Patrick Bianchi, Claudio Madonna, Stefan Wiemer, Strain heterogeneities in laboratory faults driven by roughness and wear, Earth and Planetary Science Letters,Volume 657, 2025, 119247, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2025.119247 Shalev Siman-Tov, Einat Aharonov, Amir Sagy, Simon Emmanuel; Nanograins form carbonate fault mirrors. Geology 2013; 41 (6): 703–706. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G34087.1 Shalev Siman-Tov, Greg M. Stock, Emily E. Brodsky, Joseph C. White; The coating layer of glacial polish. Geology 2017; 45 (11): 987–990. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G39281.1 Ronald L. Biegel, Charles G. Sammis, Relating Fault Mechanics to Fault Zone Structure, Advances in Geophysics, Elsevier, Volume 47, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2687(04)47002-2