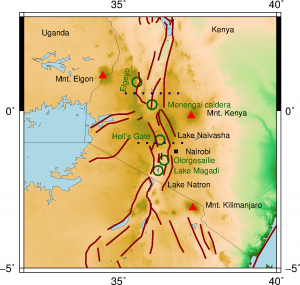

Topographic map of the Kenya rift and surroundings. Dark red lines indicated faults from the GEM database. Dotted blue lines separate the northern, central and southern Kenya rift. In green circles the discussed locations.

A little over a year ago, I was lucky enough to join a field trip to the Kenya rift organized by Potsdam University and Roma III. This rift is part of the active East African Rift System, which I introduced in a previous blog post. With a group of 25 enthusiastic participants from Roma Tre, Potsdam University, Nairobi University and GFZ Potsdam (we somehow always managed to make the 20-person bus work), we set out to study the interaction between tectonics, magmatism and climate and their link to human and animal evolution. Based on several pictures, I’ll take you through the highlights.

Basement foliation and fault orientation

Two numerical modellers looking at rocks… Gneisses of the Mozambique belt with steeply dipping foliation – I think. Courtesy of Corinna Kallich, Potsdam University.

Although this first picture might not look so impressive (I promise, more impressive ones will come), this road outcrop shows the structure of the basement that is responsible for the orientation of the Kenya rift’s three western border faults. Here in particular, we are slightly west of the Elgeyo escarpment, the scarp of the major east-dipping Elgeyo fault. It reactivated the steep foliation of the Mozambique belt gneisses that formed during the Pan-African orogeny (550-500 Ma; Ring 2014). Changes in foliation orientation are mirrored by changes in fault orientation from NNE to NW upon going from the Northern to the Southern Kenya rift (see map). The Elgeyo fault itself displaced the 14.5 My old massive extrusion of phonolite lavas that can be seen throughout the Kenya rift area, marking the start of the current rift phase. From the differences in basement level between the western shoulder and the rift centre, the total offset along the fault is ~4 km!

Rift axis volcanism

Lunch overlooking the Menengai caldera that collapsed 36,000 yr ago. Courtesy of Corinna Kallich, Potsdam University.

With on-going rifting, the tectonic and magmatic activity localised in the centre of the Kenya rift. One massive central volcano is the Menengai volcano, whose view we enjoyed over lunch. This 12 km wide caldera collapsed 36,000 yr ago; the ash flows of the eruption can be found throughout the whole of Kenya. Within the caldera, diatomite layers alternating with trachyte lava flows indicate the presence of lakes 12 and 5 ky ago. These lakes were fed by the neighbouring Nakuru basin overflowing into the Menengai crater. The volcano itself was responsible for the earlier compartmentalization of the larger Nakuru-Elmentaita basin. At the moment, freshwater springs are being fed by the groundwater, and 40 geothermal wells are being constructed to benefit from the groundwater being heated by the magma chamber at 3-3.5 km depth.

Lunch at Hell’s Gate

Looking along Hell’s Gate Gorge – cut into the white diatomite and pyroclastic layers – towards feeder dikes of the remaining core of a volcano. Courtesy of Corinna Kallich, Potsdam University.

Watching the wildlife and beautiful scenery is usually the reason people visit Hell’s Gate National Park, but we studied the flow structures in a highly viscous, silica-rich lava flow. We then scrambled our way through Hell’s Gate Gorge that cut into mostly diatomite lake sediments (these algae are very helpful) alternated with pyroclastic layers. Most impressive however, were the crosscut basaltic intrusions that we could trace back to the centre of an otherwise eroded volcanic dome. The well-deserved lunch was a rather frustrating affair, as Vervet monkeys took every chance at stealing our food, not even shying away from distracting us with their adorable babies.

Wishing the lake was back

The white diatomites of the Olorgesailie Formation, indicating the presence of a lake. Courtesy of Corinna Kallich, Potsdam University.

The Olorgesailie basin is where paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey and his wife palaeontologist Mary Leakey (Wikipedia) unearthed a score of Acheulean hand axes in the 1940s. The 600-900 ky old tools were used to dig for roots, cleave, hammer and scrape meat and can be seen in the Kariandusi museum site. Besides the hand axes (made from all the trachyte found in the area), we marvelled at the Olorgesailie Formation that contains them, which was deposited between ~1.2-0.5 Ma. The formation consists of repetitions of wetland, river and lake sediments and paleosols (fossil soils, indicating dryer conditions). As we stand baking in the sun on top of the dusty, white diatomite, the vision of a lake sure is very alluring.

A not-so-fresh lake

On our way to a tiny hotspring along the edge of the slightly pink waters of Lake Magadi. In the foreground the white evaporates the lake is mined for. Courtesy of Corinna Kallich, Potsdam University.

While we mostly stayed in resorts, our only campsite (proper “glamping” with a shower and bathroom in the tent) was close to Lake Magadi, one of the lakes along the rift axis. This saline, alkaline lake gave its name to magadiite, a sodium hydro silicate, that when dehydrated forms chert (i.e. flint). The lake is also mined for its sodium carbonate, known as trona. During the African Humid Period (15,000-5,000 yr ago; Maslin et al. 2014), Lake Magadi was about 40 m higher, a lot fresher and connected to Lake Natron further south. Fun fact from Wikipedia: elephants visit the Magadi Basin to fill up on their own salts supplies as well. From my own experience, I can tell you, it does not taste very good.

My trusted companions for over a decade did not survive Kenya’s heat and volcanics… Serves me right for not taking them out often enough!

And then there were the hippos, neptunic dikes, dancing Maasai, a boat trip to the hydrothermal vents on Ol Kokwe Island, giraffes outside our cabin, midnight stargazing… too much to capture in one blog post. I had a wonderful time in Kenya exploring the geology, admiring the wildlife and getting to know its people. My only regret? Losing my shoes…

References: Maslin, M. A., Brierly, C. M., Milner, A. M., Shultz, S., Trauth, M. H., Wilson, K. E. (2014). East African climate pulses and early human evolution, Quaternary Science Reviews 101, 1-17. Ring, U. (2014). The East African Rift System, Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences, 107, 1. Strecker, M. R., Faccenna, C., Wichura, H., Ballato, P., Olaka, L. A. and Riedl, S. (2018). Tectonics, seismicity, magmatic and sedimentary processes of the East African Rift Valley, Kenya, Kenya Field School Field Guide. Personal communication with Strecker, M. R., Wichura, H., Olaka, L. A. and Riedl, S.