The 4.5 billion years of geologic evolution has shaped the tectonic processes in Earth we see today. Over the span of time, Earth has changed from being a magma ocean to a tectonically active planet, by transitioning through different tectonic regimes. A silent witness of this journey have been cratons which have survived for billions of years. Therefore cratons preserve clues of past tectonic processes. Interestingly, edges of the cratonic lithosphere are also known to host an orchestra of critical mineral deposits, which makes them economically valuable. Today, we are going to look into different processes that contribute to formation, stability and destruction of the cratonic lithosphere and how they become hotspots of mineral deposits.

Formation of cratons, insights into early Earth

The tectonics of early Earth has always fascinated the geodynamics community, since the geologic conditions under which the continents and cratons formed are different from what we see today. A significantly hotter mantle at that time drove vigorous convection, widespread melting to form early crust, and rapid crustal recycling, likely producing a tectonic regime very different from modern plate tectonics.

Hungry readers can find a plethora of posts in the Geodynamics blog about early Earth. In this post Fabio Capitanio described how vigorous convection, and melting events in early Earth, produced basaltic crusts, which were re-melted and reworked potentially producing TTGs which are characteristics of early crusts. Several other blogs addressed the topics of early archean crustal formation and pre-plate tectonics. These melting events leave behind a depleted and hydrated mantle, which can gradually accrete over time to produce cratonic blocks. Now, how do these cratonic blocks survive for billions of years?

Stability of cratons

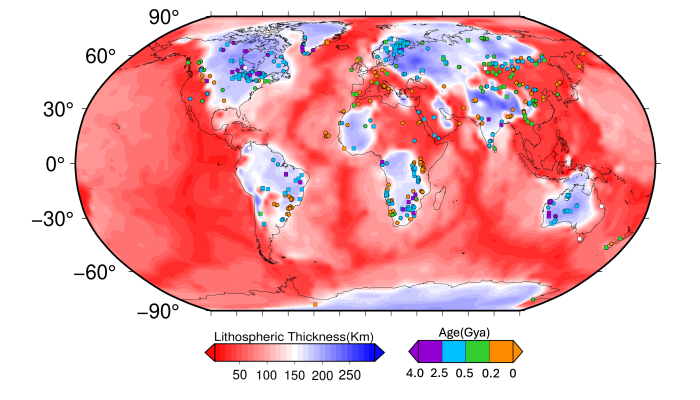

Eventually over time the continental blocks might come together to ultimately form cratons, which have deep lithospheric keels extending 150 to 250 km into the mantle.The key factors attributing to their long-term stability are (Lee et al., 2011):

- Chemical buoyancy: The melting events which formed the early continents, extracted and removed the dense Iron rich component from the mantle, making the residue of a lower density compared to that of a fertile mantle. This chemically depleted layer contributes to its compositional buoyancy, which helps offset a negative thermal buoyancy due to cooling of the lithosphere over time.

- Mechanical strength: The melting events also dehydrates the residue. This removal of water, changes its rheology, making the material stronger, more viscous and difficult to deform. This rheologically stronger layer coincides with the chemically depleted layer, to create a stable continental block.

For further details about craton stability, readers can check this blog. Together, these processes explain how cratons have survived for billions of years. But, indestructibility is boring and a twist in the story always makes it more interesting!

Destruction of cratons

Now, while most cratons are exceptionally stable, some of them cannot escape the wrath of tectonic forces, hence leading to their destruction. An example of this is the north China craton. The key mechanisms contributing to destructions of cratons (Lee et al., 2011) are:

- Rheological weakening: Adding hydrous material to the continental mantle, would dramatically weaken it, therefore lowering its viscosity. The continental mantle would then be more susceptible to convective removal.

- Thermomagmatic erosion: Mantle plumes or upwellings can heat the lithosphere from below or fertilize the cratonic roots. This reduces viscosity and density contrasts, making cratonic lithosphere relatively less stable.

- Convective removal and edge-driven instabilities: When the lithosphere has already been thermally and chemically weakened, it can induce small scale convection, which might then remove the weakened lithosphere.

Mineral deposition along cratonic edges

While cratons are of great scientific interest to geologists to understand the evolution of Earth, they also have significant economic importance. Cratonic edges host some of the most valuable critical minerals, which are very important for society. Some of the mineral deposits they host are:

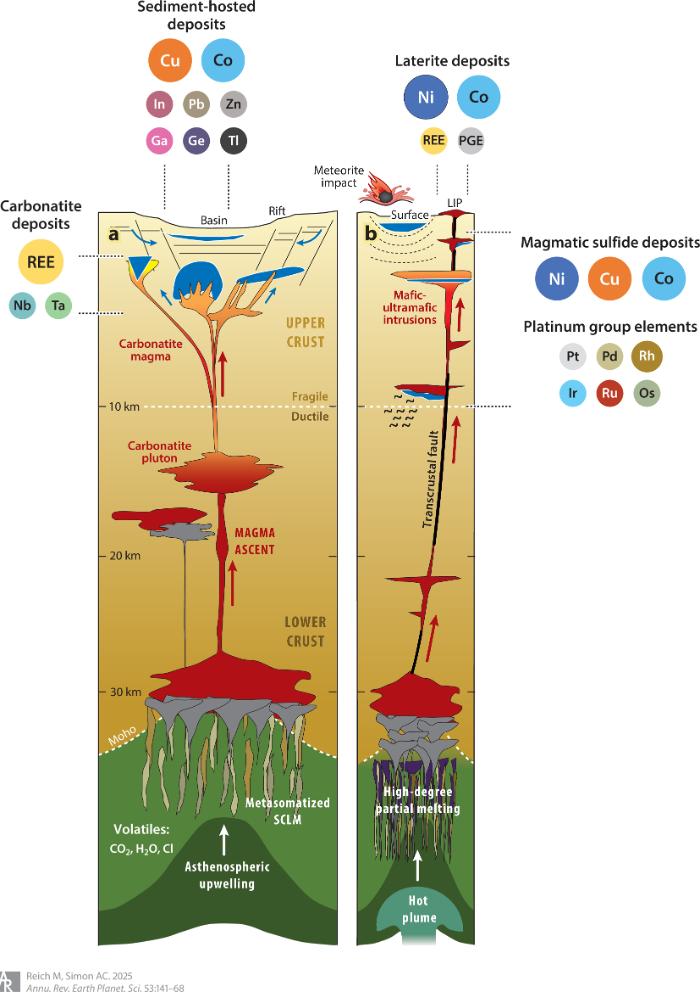

- Rare Earth Element (REE) deposits are hosted in carbonatites, which commonly occur along cratonic margins. Sometimes these cratonic margins are modified by subduction related fluids and metasomatism events. These make the region enriched in incompatible elements and introduce small amounts of CO2 . Now, when this carbonated mantle undergoes melting, after being heated up by a mantle plume, they produce carbonatite magmas which might be rich in REEs (Gibson et al., 2024).

- Ni-Cu-PGE (Platinum group elements) deposits also occur within 100 km of the cratonic edge. These types of deposits are a result of high degree of partial melting from a mantle upwelling. When a mantle plume rises beneath a thick lithosphere, it is deflected sideways into areas of thinner lithosphere, producing high-degree of melting. Fault structures along cratonic edges might also guide these magmas upward. This magma then interacts with the crust to form sulphide deposits. (Begg et al., 2010; Griffin et al., 2013).

- A majority ( 85%) of sediment hosted metals like Cu, Zn, Pb lie within ~200 km of the transition between thick cratonic lithosphere and adjacent thin lithosphere (Hoggard et al., 2020). During rifting the cratonic lithosphere produces deep basins which can accumulate 8-9 km thick sediment piles. Owing to a thicker and cooler cratonic root, the whole basin stays within a temperature of around 250 oC, which is considered a sweet spot for operation of various oxidation-reduction reactions to precipitate minerals. Therefore, thicker cratonic basins have ideal conditions for forming large sediment-hosted metal systems as shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1: Schematic model for REE and Ni-Cu-PGE deposits. Figure (a) shows geodynamic conditions favouring REE deposits, which form in cratonic rifts. The model shows all geologic processes starting with formation of melts and fluids from the metasomatized mantle, right until their emplacement in the upper crust. Figure (b) shows geodynamic processes in magmatic sulphide deposits. It shows how high-degree melt generated from mantle plumes migrate to crust and form this type of mineral deposits (Figure taken from Reich and Simon, 2025).

It is also important to consider that, while cratons provide optimum conditions for development of mineral deposits, edge stability of the cratonic lithosphere also plays an important role in enhancing the preservation potential of all mineral deposits. A mineral deposit is more likely to survive future orogenic events and supercontinent cycles, if it is present at the edges of cratons compared to normal lithosphere (Hoggard et al., 2020).

Cratons are among the oldest surviving pieces of lithosphere. Studying evolution of cratons through geological time provides us with valuable clues to understand early Earth and precambrian geodynamics. But their importance doesn’t end there. Since cratons are hosts to major critical minerals, it is not only a record of Earth’s past but the key to its future, due to the ever increasing demand of these minerals, which makes their study a tad more interesting. The geologic processes that shape cratons and control mineral systems are closely linked and hence studying evolution of cratons can help us establish direct links between mineral systems and global geodynamics.

References: 1. Begg, Graham C., Jon A.M. Hronsky, Nicholas T. Arndt, William L. Griffin, Suzanne Y. O’Reilly, and Nick Hayward. ‘Lithospheric, Cratonic, and Geodynamic Setting of Ni-Cu-PGE Sulfide Deposits’. Economic Geology 105, no. 6 (2010): 1057–70. https://doi.org/10.2113/econgeo.105.6.1057. 2. Capitanio, Fabio A., Oliver Nebel, and Peter A. Cawood. ‘Thermochemical Lithosphere Differentiation and the Origin of Cratonic Mantle’. Nature 588, no. 7836 (2020): 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2976-3. 3. Gibson, Sally, Dan McKenzie, and Sergei Lebedev. ‘The Distribution and Generation of Carbonatites’. Geology 52, no. 9 (2024): 667–71. https://doi.org/10.1130/G52141.1. 4. Griffin, W. L., G. C. Begg, and Suzanne Y. O’Reilly. ‘Continental-Root Control on the Genesis of Magmatic Ore Deposits’. Nature Geoscience 6, no. 11 (2013): 905–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1954. 5. Hoggard, Mark J., Karol Czarnota, Fred D. Richards, David L. Huston, A. Lynton Jaques, and Sia Ghelichkhan. ‘Global Distribution of Sediment-Hosted Metals Controlled by Craton Edge Stability’. Nature Geoscience 13, no. 7 (2020): 504–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-020-0593-2. 6. Lee, Cin-Ty A., Peter Luffi, and Emily J. Chin. ‘Building and Destroying Continental Mantle’. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 39, no. 1 (2011): 59–90. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-040610-133505. 7. Shuang-Liang LiuLin MaXinyu ZouLinru FangBen QinAleksey E. MelnikUwe KirscherKui-Feng YangHong-Rui FanRoss N. Mitchell; Trends and rhythms in carbonatites and kimberlites reflect thermo-tectonic evolution of Earth. Geology 2022;; 51 (1): 101–105. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G50775.1 8. Martin Reich, Adam C. Simon. 2025. Critical Minerals. Annual Review Earth and Planetary Sciences. 53:141-168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-040523-023316 9. Priestley, Keith, Tak Ho, Yasuko Takei, and Dan McKenzie. ‘The Thermal and Anisotropic Structure of the Top 300 Km of the Mantle’. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 626 (January 2024): 118525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118525. 10. Smith, W. D., and W. D. Maier. ‘The Geotectonic Setting, Age and Mineral Deposit Inventory of Global Layered Intrusions’. Earth-Science Reviews 220 (September 2021): 103736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103736.