Image credit: Piqsels.

Who doesn’t love baking? Seriously, baked goods are the best: with or without gluten, with or without chocolate. But you know what makes every bake out there even better? A geological theme. You heard it here first! This week, Ruth Amey, postdoctoral researcher and programme manager of the Earth Observation Center for Doctoral Training at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom, discusses the best geological bakes she has come across in a thoroughly peer-reviewed article. On your marks; get set; read!

Abstract

In this work we present the findings of many years of geobake experiments. We take inspiration from seismology, active tectonics, but also branch into geochemistry and mineralogy. We find geocakes to be both delicious and informative.

Methods

Weighting, pouring, sifting, beating, mixing, folding, baking and excessive spoon-licking.

Results

Focal mechanism cake

Expanding from our previous work in sponge cake and butter cream, we first conducted this geocake experiment.

Here we present a focal mechanism – a 2D picture explaining how an earthquake moved at depth. This focal mechanism cake demonstrates that the earthquake was mostly an extensional earthquake (pulley-tuggy) with some strike-slip (sidey-waysey) motion, adopting the (very amusing) terminology of Mark Tingay.

Focal mechanism cake.

With credit to Miriam Gordon, who baked this with me in our university accommodation kitchen for Richard Holtham’s birthday.

This geobake also shows the picked locations (here, those silver balls, that you’re never quite sure if they’re edible. I’m pretty sure they are edible). The first arrival from an earthquake could either be up or down (compressional or extensional) depending of the orientation of the fault (the ‘strike’). By using lots of seismometers all over the world, these first arrivals help us work out the orientation and type of earthquake.

This needs just buttercream and chocolate buttercream to create a striking cake (pun intended). The design can also be easily updated for different types of earthquakes, and lends itself well to cupcakes.

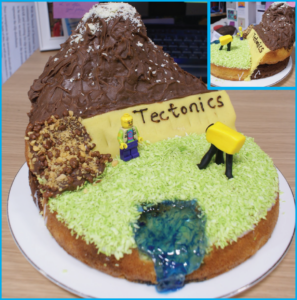

Alluvial fan normal faulting cake

In this next experiment, we chose to explore and quantify the geomorphological effects of active faulting, as well as experimenting with icing of different rheologies. It can be seen from the cross section (side cake view) that this earthcake has been uplifted repeatedly over time. The folded sediments (marbled chocolate and vanilla sponge) overlying the strong, carrot cake basement have been uplifted by active faulting and eroded by blue fondant rivers. The erosion results in ‘wine glass canyons’, where the eroded chocolate-vanilla cake forms the cups of the glasses and the stems of the glasses are the granola alluvial fans, where the rivers have deposited their delicious load upon reaching flat ground. Note: Lego man is not to scale.

Normal faulting cake.

With thanks to David McKenzie, Tim Middleton and Yu Zhou, who baked this with me for the COMET (The Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics) entry to the 2013 Oxford annual Geobakeoff.

This cake takes on the challenge of making a three dimensional cake, with satisfactory results. The ‘folded sediments’ are made by a simple marbling method of chocolate and vanilla cake batters (aka ‘zebra cake‘) and is simple to make, but effective.

Seismometer Swiss roll

In previous literature (mostly blockbuster films), seismologists tear off a reel of graph paper spat out by a seismometer, look into the distance and mutter ‘it can’t be?!’. Here we replicated this experiment with a seismometer swiss roll. To make our graph paper we drew icing lines on the baking tray before pouring in the cake mixture, so those squares are baked in. Then we drew out the arrivals of the P waves with a milk chocolate, followed by S waves, and then the surface waves.

Seismometer Swiss roll cake.

Credit to Katy Willis and George Taylor; we baked this for the 2017 Earth and Environment Geobakeoff.

Note that even when seismometers did rely on a pen drawing on graph paper, the graph paper was rarely filled with jam and cream.

2016 Italian earthcake sequence

To continue with our work on normal faulting earthquakes, here we focused on the 2016 Italian earthquake sequence. At Mounte Vittore a pre-existing (marzipan) fault scarp was exposed more in the Visso and Norica earthquakes. Our colleagues at the University of Leeds, Laura Gregory, Huw Goodall, and Luke Wedmore, took a laser scanner (a real one, not one made of fondant, as seen in this cake) into the field to scan these faults. Here we captured their reported landslides in honeycomb and new springs in melted boiled sweets. As always, lego man is not precisely to scale, though the freshly exposed fault scarp from these earthquakes was slightly over one PhD student high.

2016 Italian earthcake sequence.

With thanks to Katy Willis for baking this with me for the Tectonics entry to the 2018 Leeds School of Earth and Environment Geobakeoff.

Discussion – Viva cakes

Following the successful experiments described above, we further pursued this line of research by trying to capture PhD theses in cake form.

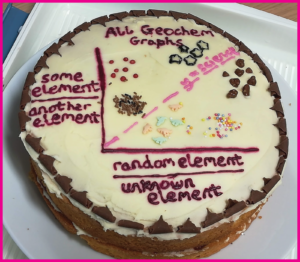

Geochemistry cake

Geochemists everywhere I implore you – when plotting graphs of element ratios against element ratios it would be extremely useful when giving a talk to explain why you have chosen these ratios, or what these ratios mean. Otherwise it’s just some element over another element, against a random element and an element I’ve never heard of. I had this ongoing joke with Patrick Sudgen, and so baked this for his viva cake. The viva and members of the Institute of Geophysics and Tectonics research group at Leeds all agreed that it wasn’t accurate as it had far too many data points for a geochemistry graph. But no one could deny that y = science.

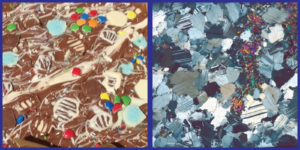

Thin section millionaire shortbread

I feared this bake might have been indistinguishable from a chocolately mess that a child might make when left unattended, but when I gave it to Amicia Lee for finishing her viva she thankfully recognised it, unprompted, as thin section millionaire shortbread.

One of these pictures is a cake. The other is a picture of about 1 cm of South Harris anorthosite taken down a microscope by Amicia Lee. Can you spot the difference?

Down the microscope, under cross polarised light, thin sliced rocks really look like this (the picture on the right, not exactly like the one on the left). The mineral plagioclase shows ‘twinning’ – zebra stripes because the crystals grains grow interlocked, with some showing as black and some showing as white. This can also be seen in white chocolate buttons with milk chocolate lines, or milk chocolate buttons with plain chocolate lines. Depending on the position of your millionaire shortbread, of course. The brightly coloured smarties are (I had to check with Amicia on this one) mostly clinopyroxene but some of it has been altered to hornblende. The edible green glitter is just for show, really.

That’s the most hard-rock geology this geophysicist has done in a while! And I should say the inspiration for this bake came from Katy Burrows on twitter – I think she pulled it off somewhat better than me!

Discussion – Other literature

In this section I’d like to highlight other noteworthy geocakes I’d had the pleasure to review (i.e., eat).

They include:

• Top left – Mal McMillan’s interferogram cake – funky colours compulsory

• Top right – Paleo at Leeds’ excavation cake (winners of 2017 School of Earth and Environment Geobakeoff)

• Bottom left – Volcanology’s entry to the 2018 School of Earth and Environment Geobakeoff (complete with interfero-sprinkles – they don’t sell sprinkles separately, you know. They separated them by hand)

• Bottom right – a convection cake by Claire Harnett, from Ben Todd’s thesis.

For more excellent and inspiring geobakes, I refer the reader to the Great Geobakeoff page, and references therein.

Conclusions

Key findings and parting thoughts:

• Cake is delicious; geocake especially so.

• When choosing decorations, remember that dinosaur sprinkles give somewhat ambiguous x,y locations on graph cakes

• Angel cake must have been deposited during a remarkably tectonically calm period, with no faulting or folding.

• Cookies that have expanded to form one Mega Cookie, à la Giants Causeway, provide both a learning experience and an excuse to eat Just One Cookie.

Geobaking gives the baker the opportunity to reflect on their work and to think about how to best present science visually, in an appetising way. Additionally many great ideas begin with conversations with colleagues over a cup of coffee and potentially a slice of cake – and what better cake for science to stem from than geocake?

We implore the reader to continue this line of research and there are no supplementary materials associated with this work, because we have eaten them all.