As temperature records have continuously been broken all over the world, many of us scientist had to endure extreme conditions in our overheated offices. Climate change is happening, and faster than we’d like to think, but how does this play a role in the scientific community? In this week’s blog post, geodynamicist Nicolas Coltice (professor at Ecole Normale Superieure de Paris) shares his passionate opinion on the matter and sheds light on several important topics that may easily be overseen by enthusiastic scientists.

Nicolas Coltice is a professor in the Laboratoire of Geology of Ecole Normale Supérieure de Paris.

I took my last flight for work in May 2017 to go to a meeting of the Deep Carbon Observatory in Moscow. I had started evaluating my carbon footprint a couple of years before, and flying to do science on carbon questioned me. The first flight I ever took was when I was about 14, to go to a place close to Chernobyl (in the U.S.S.R. at the time), a few years after the catastrophe. It seems that Russia brings me back to environmental questions. In the context of climate change today, many scientists give their opinions on the future. Civilization will collapse, or science will magically save us all. There is so much abstract agitation and noise in the debates. Both the exploitation of nature and pollution impact landscapes and the living so quickly. What will the world be like in 30 years? Who can guess rationally?

Climate countdown

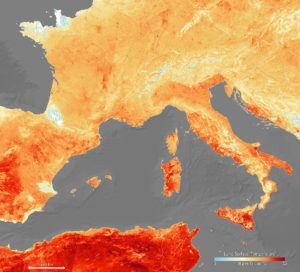

When I started to write this blog post, it was June 13th. The temperature in Delhi was about 48°C and the Monsoon did not seem to start. Water shortages led to fights with people being killed. In Poland, temperatures reached over 30°C. But in France, temperatures were cooler and close to those occurring in Greenland. A few weeks later, we had the highest temperatures ever recorded in the South of France. Particles and pesticides are all over the place and we eat and drink litters of them every year. Climate will continue to change: even if we stop emitting carbon and methane, the ocean will keep on doing so for centuries.

Surface temperature of some European countries on June 27th 2019 (European Space Agency).

The IPCC and diverse agencies have given a very simple recommendation: by 2030, we have to lower our carbon emissions by 50%. That is 11 years from now, soon to be 10, soon to be 9… In the next 10 years, there is minimal chance that humanity has developed new energy sources for the billions of people all over the world. For example, building a nuclear power plant takes years, and it can only distribute energy about 10 years after completion. Besides blaming politics and big companies, what can one do here and now? Because the shift of society does not seem to start in comfortable offices, it has to start everywhere. It is now. What actions can we take as geodynamicists? In geodynamics we tackle problems with a large vision, including long-range dependencies, evaluating the forces at play.

Because the shift of society does not seem to start in comfortable offices, it has to start everywhere.

I started to think about our job as a scientist. Many carbon footprint tools help us identify how to mitigate our carbon emissions. The Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research proposes guidelines for low-carbon research, that are quoted here: ”

-

- Monitor and reduce. I will keep track of the carbon emissions of my professional activities, and set personal objectives to reduce them in line with or larger than my country’s carbon emissions commitments (…).

- Account and justify. I will justify my travel considering the location and purpose of the event, my level of seniority, and the alternative options available.

- Prioritise, prepare and replace. For activities that I organise, I will choose the location giving high priority to a low carbon footprint of travel of the participants, and I will encourage, incorporate and technically support online speakers and webcasts to reduce unnecessary travel.

- Encourage and stimulate. I will resist my own FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) from not attending everything and work towards sensitizing others to the need of the research community to walk the talk on climate change.

- Reward. I will work with my peers, Institute and Funders to value alternative metrics of success and encourage the promotion of low-carbon research as a realisable alternative to a high-carbon research career.”

The Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research also provides a Travel Strategy (link to PDF) that aims to help individual researchers to reduce their emissions through time.

Emit carbon or perish

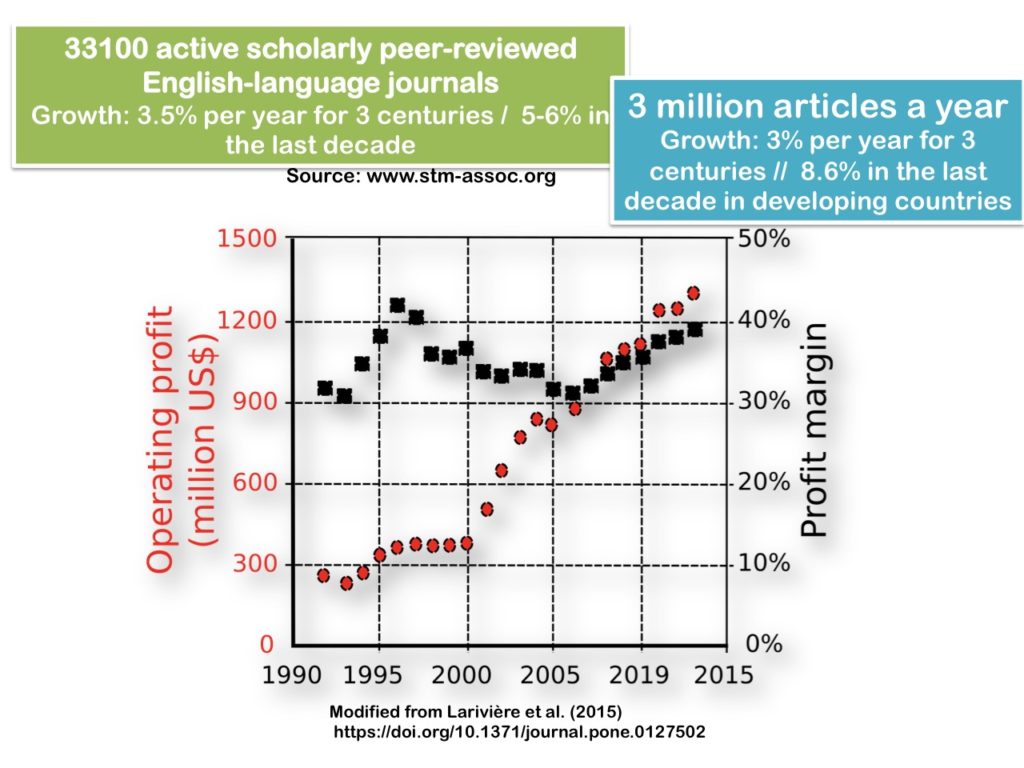

This is essentially dealing with travel, clearly the main source of scientists’ carbon footprint. Let’s identify the forces at play that make us using tons of carbon every year on average. I identify a major shift in our practice between 2000 and 2010, with digital doping of the old “publish or perish”. It would be easy to blame computers. Private companies build publication databases with our work to compile performance indicators of individuals. Now a handful of business groups own most of the journals, questing increasing financial profit (Elsevier and Springer operated a better profit margin than Apple in 2014, 37% and 35% respectively). What was common (not state-controlled but controlled by the scientific community) became increasingly private and marketable. Growth of publication numbers generates billions of euros of dividends for stakeholders, at the expense of public money. Every year subscriptions cost more to the scientific community (see for instance the website of the University of Virginia Library). And we are now productive workers in a globalised science-market. It is for granted that competition is the source of good science… or in any case good money. Therefore, scientists have to publish more, be everywhere to “sell” their results or see which ones they “buy”, and hence travel all over the world.

Journal and articles figures for 2018 by the STM association. Profit data for the Scientific, Technical & Medical division of Reed-Elsevier only (Larivière et al., 2015) .

Competition-strategy modifies the science itself, introducing loss of integrity (Fanelli, 2010), and of course dramatically increasing our environmental impact. We are pushed to acquire the most powerful machines, generate the biggest datasets, do large-scale analysis, publish as many papers as we can, and travel the world to disseminate the results. Or perish. Bigger machines often require less energy to obtain the same performance as the old ones. However, the energy gain of new technology becomes more than compensated by accentuated use of it. This is the rebound effect. New technology is not a substitute but an addition. Hence we need more energy and more natural resources. Can we substitute instead of add? Can we identify when it is so easy to use machines instead of our brains, but somewhat irrelevant to do so?

Scientists have to publish more, be everywhere to “sell” their results, or see which ones they “buy”, and hence travel all over the world.

Although planes are getting more carbon-efficient, travel for science has become intensive. Some colleagues like their job because they can travel, which I understand. The number of conferences and workshops exploded. The increase in attendance of worldwide meetings like AGU (11,422 attendees in 2004 and 21,702 in 2012) questions their role in terms of scientific relevance and impact on the planet. What shall we do with all these gatherings? Mobility looks like a necessity today. However, research has shown that limiting the use of planes to travel has barely any impact on scientific careers (Wynes et al., 2019).

(Lower-carbon) Science as a common

Competing, publishing as much as possible, privatising science and transferring public money to the stakeholder of publishing groups constitute a dead-end for our job. This is a dead-end for science. This is a dead-end for knowledge and humanity. Exponential growths of h-index, publication rates, data collection and conference travel are not sustainable. The rebound effect often kills the gain of progress for production gain. Can we make a transition as a community, building our commons and collaborative organizations? Can we start to teach new research ethics and practices so the new generation will be ready to do this job in a sustainable way? We have 10 years, soon to be 9.

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., and Mongeon, P. (2015). The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127502 Fanelli, D. (2010). do Pressures to Publish Increase Scientists' Bias? And Empirical Support from US States Data. PLoS ONE 5(4): e10271 Wynes, S., Donner, S. D., Tannason, S. and Nabors, N. (2019). Academic air travel has limited influence on professional succes. Journal of Cleaner Production 226: 959-967

Ed Garnero

Awesome to read this. I hope that, soon, virtual attendance to conferences will be common, simple, and meaningful