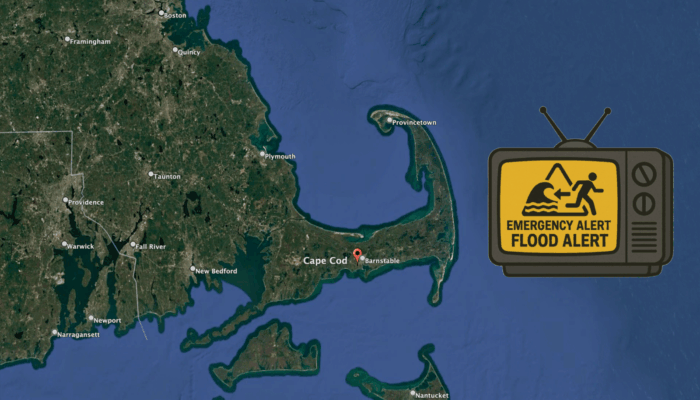

This week I think back on my time in the United States of America, where I was able to spend the holiday season. In North America, “fall” marks the beginning of this holiday season, and symbolises a time filled with traditions of togetherness that transcends regions. In New England, particularly in the state of Massachusetts, the season is synonymous with crisp air, vibrant foliage, and the celebration of Thanksgiving. The past year, I found myself spending a public holiday in the company of my partner’s family on Cape Cod, which is the scenic peninsula just southeast of Boston. Amidst the warmth of the festivities and the quiet charm of “the Cape”, unexpectedly the television broadcast – playing sports events in the background – was abruptly interrupted by a blaring alarm sound: a test of the region’s early warning system.

To understand the context behind the alert experience, it is worth explaining the early warning system in the USA and how it operates. The Emergency Alert System (EAS) is the national public warning system designed to deliver critical emergency information to affected communities. Managed collaboratively by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS), the system ensures that alerts—ranging from severe weather warnings to AMBER alerts—reach the public via radio, television, and other communication platforms. Whilst local authorities often issue alerts in response to regional events, FEMA oversees national-level activations and system-wide tests, ensuring readiness for any potential large-scale emergency [1]. Regular testing of systems like the EAS is a crucial part of this preparedness, ensuring that communities remain familiar with emergency protocols and reinforcing public trust in the tools designed to keep them safe.

The Cape Cod landscape and hazard-related risks

Cape Cod, a glacially-formed peninsula in Massachusetts, showcases a landscape shaped by retreating glaciers during the last Ice Age, featuring sandy beaches, dunes, and kettle ponds. Composed primarily of unconsolidated sand, gravel, and glacial till, its terrain is continually reshaped by tidal forces and coastal erosion. While the scenic beauty attracts visitors, Cape Cod’s low-lying geography and reliance on sandy soils make it particularly vulnerable to natural hazards such as coastal storms, Nor’easters, and hurricanes, often accompanied by storm surges and flooding. Rising sea levels and ongoing erosion exacerbate these risks [2].

Cape Cod National Seashore, despite being a model of collaborative conservation, faces growing risks from coastal hazards, including flooding, erosion, and storm surges, intensified by climate change and rising sea levels. Climate-driven impacts, such as more frequent extreme weather events and accelerated shoreline erosion (Fig. 1), threaten 12% of its infrastructure, with key assets like trails and roads particularly vulnerable due to inadequate elevation and protective measures. With 11% of assets highly vulnerable, proactive adaptation strategies (e.g., relocating infrastructure and dune and wetland restoration projects to serve as natural buffers) and early warning systems are critical to mitigating risks and safeguarding this dynamic coastal environment from the compounded effects of climate change. Given these challenges, adaptive measures such as relocating vulnerable infrastructure, as seen at Herring Cove Beach, have been implemented to reduce exposure to hazards [3, 4]. For long-term resilience planning, authorities at Cape Cod National Seashore are incorporating NOAA storm surge models to assess future coastal flood risks and inform decisions about infrastructure relocation, dune restoration, and visitor safety measures [5]. Such vulnerabilities highlight the critical role of early warning systems like the Emergency Alert System (EAS) in protecting residents and visitors from the dynamic risks of this unique environment.

Fig. 1 – Kalmus Beach in Hyannis, one of the shorelines affected by coastal erosion within the Town of Barnstable, Cape Cod, Massachusetts (Image credit: the author).

The warning test on Turkey Day

Thanksgiving – or “Turkey Day” as it is affectionately known — is a time when the main event is dinner, and the house is full of family, food, and conversation. That afternoon, when the television suddenly cut out and started beeping with a warning message, the room fell silent. Everyone turned to stare at the screen, except for the children, who carried on playing as if nothing had happened. It was just the EAS test, followed by the familiar message reassuring everyone and reminding people there was no need to panic, just another regular test.

What struck me most was how unfazed the children were. These tests happen so regularly that, as one parent explained, they are used to it and know what to do. Later, a local I spoke with shared a similar memory from her own childhood on the Cape. “We would fall asleep with the TV on, during summer stays, and it was not uncommon to wake up to that alert sound,” she told me. “It never really scared us. Growing up navigating these small beach towns, you see ‘evacuation route’ signs everywhere. But no one panics – because the systems work, and people are prepared.

You learn to live with it, and that reassurance comes from having good tools and infrastructure in place.”

It sparked a conversation about how communities adapt, and how familiarity, trust, and preparation shape public response to early warnings. The system is not just a siren or a message on a screen. It is a relationship between the people, the infrastructure, and the culture of readiness.

The warning culture: Be prepared, don’t be scared.

What I witnessed on Cape Cod was a small, everyday example of how a culture of preparedness can shape people’s attitudes towards risk. Regular exposure to warnings, clear public messaging, and visible infrastructure like evacuation routes all foster a sense of calm capability rather than fear. It is a reminder that early warning systems are most effective not only when they function well technically, but also when the communities they serve trust them and know how to respond.

As climate change accelerates the frequency and severity of hazards worldwide, building this culture of readiness is more important than ever. Whether in the coastal towns of New England or across the flood-prone plains of Europe, the message is the same: be prepared, don’t be scared. Through reliable systems, informed communities, and consistent public engagement, we can transform alerts from sources of anxiety into tools of reassurance and resilience.

References

[1] Federal Communications Commission (FCC). (n.d.). Emergency Alert System (EAS). Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://www.fcc.gov/emergency-alert-system

[2] Hammar-Klose E.S., Pendleton, E.A., Thieler, E.R, Williams, SJ., 2003, Coastal Vulnerability Assessment of Cape Cod National Seashore (CACO) to Sea-Level Rise, U.S. Geological Survey, Open file Report 02-233 http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2002/of02-233/

[3] Peek, K.M., H.L. Thompson, B.R. Tormey, and R.S. Young. 2023. Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Cape Cod National Seashore: Summary of Results. NPS 609/187575. Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, N.C. https://pubs.nps.gov/eTIC/CACO-CHIS/CACO_609_187575_0001.pdf

[4] USGS (United States Geological Survey), Processes controlling coastal erosion along Cape Cod Bay, MA. 2021. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/publications/processes-controlling-coastal-erosion-along-cape-cod-bay-ma (Accessed: 12 May 2025).

[5] National Park Service (NPS), 2023. Building Climate Resilience in U.S. National Parks. [online] Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/building-climate-resilience.htm [Accessed 12 May 2025]

Post edited by Hedieh Soltanpour and Navakanesh M Batmanathan