The frequency and severity of extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, droughts, and storms, are increasing globally, putting societies and infrastructures worldwide at risk [1]. These developments demand effective adaptation measures and ways to enhance societal resilience. Consequently, it is necessary to understand how people perceive and respond to natural hazards. Knowing that the occurrence of such events is likely to change in the future, it is apparent that there is also a need to understand better how that change in occurrence, protective behaviour, and societal resilience are connected.

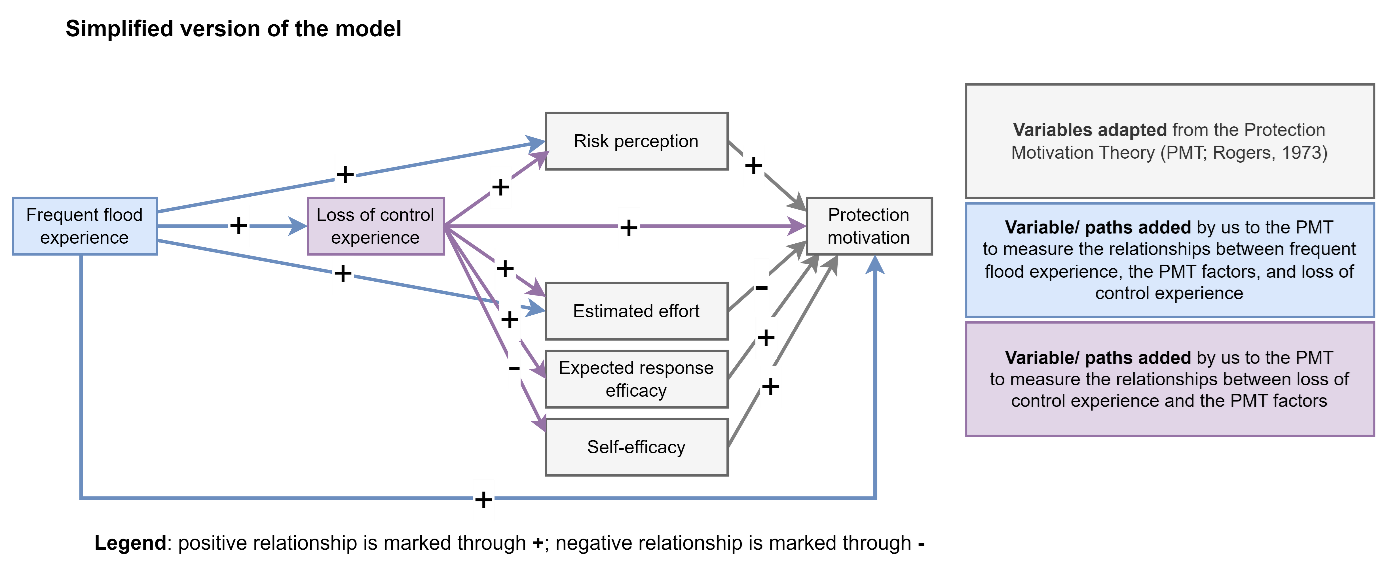

To introduce the aforementioned, our study links frequent flood experience to flood risk perception, sensed coping appraisal, and protective behaviour. Furthermore, we added an affective measure for flood experience to the model: sensed powerlessness during the last flood, defined as loss of control experience (see Fig. 1, 2).

Fig.1 – Simplified version of the model to analyse the relationships between frequent flood and loss of control experience, flood risk perception, coping appraisal, and protective behaviour

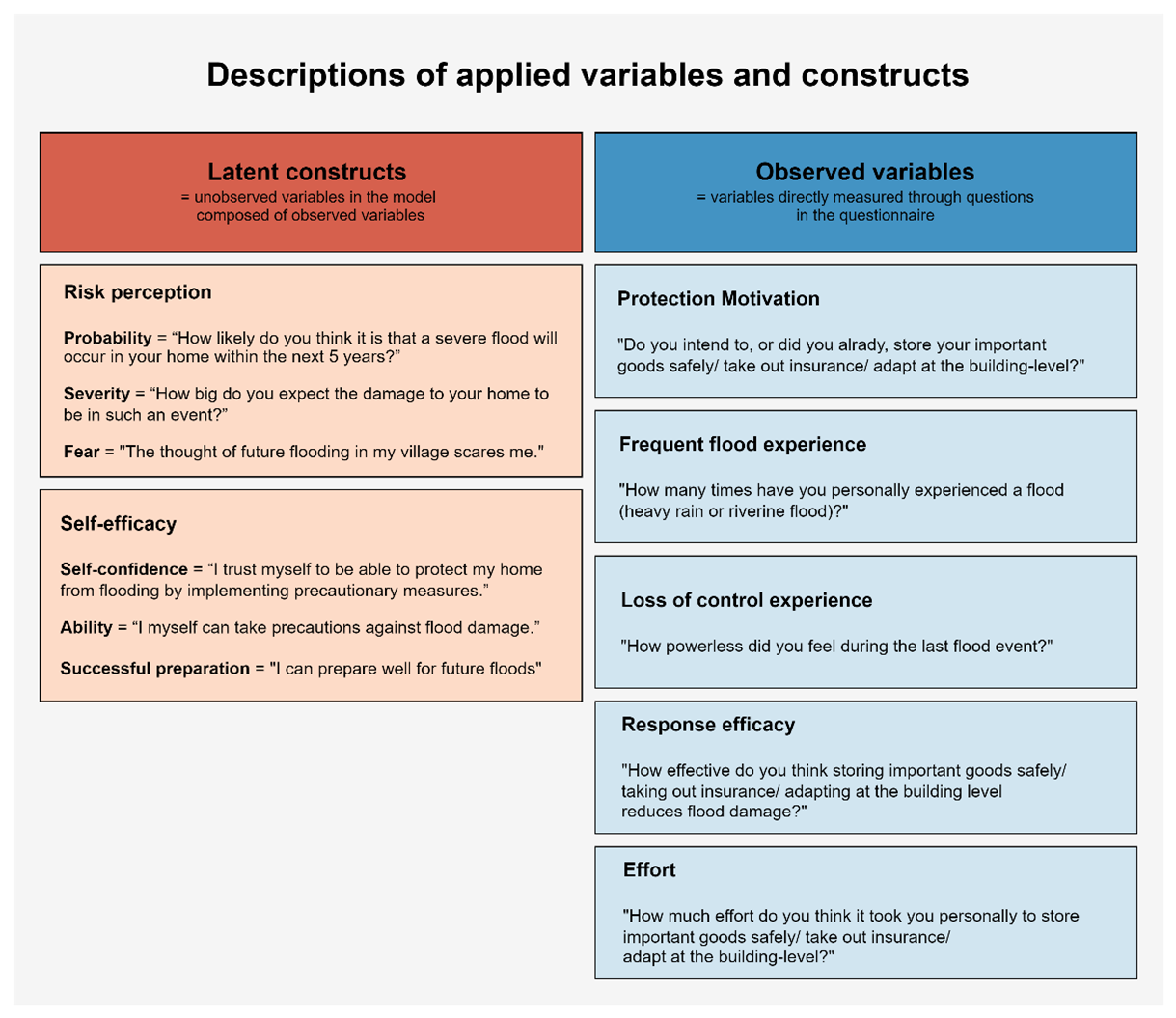

Fig. 2 – Description of variables and constructs that are part of the model

The protective actions we looked at are implementing building-level adaptation to prevent water from entering the house, storing important goods safely to secure them from damage, and buying insurance to be protected financially.

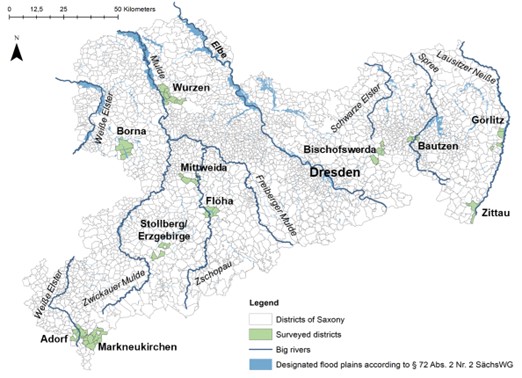

The data applied was collected as part of a project by the Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ, Leipzig) in 2020 and 2021 [3]. With the help of many students and research assistants, questionnaires were distributed to private households and collected a few weeks later. Due to this effort, the team has collected data from over 2,200 residents from the federal state of Saxony (Germany, see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 – The federal state of Saxony, surveyed districts, major rivers, and designated flood plains; created with ArcGIS, layer sources: districts of Saxony [4], big rivers [5], designated flood plains [6]

The manifold meanings of experience: what are we talking about when discussing frequent flood and loss of control experience?

Picture of Zittau, one of the cities where the questionnaires were distributed (photo credit: Sungju Han)

During the development of the study and the review of existing literature, we discovered a wide range of definitions researchers have used to describe flood experience. Some have defined it as being affected at least once or never, facing financial loss, being indirectly impacted through media coverage or family members, experiencing disruptions to public infrastructure, or encountering a specific water level in the home. Only a few studies have looked at how many floods people have experienced, thereby accounting for chronic exposure.

This is where our study comes into play. We defined experience as the perceived number of floods a person has been through. Moreover, we introduced a psychological measure—loss of control experience – which captures individuals’ sense of powerlessness during their last flood event. We hypothesised that the impact of experienced frequency on risk perception, coping appraisal, and protection motivation might be influenced by emotional response. In other words, if a person has experienced and managed three flood events well, they might perceive the risk of flooding as less severe than someone who has experienced the same number but felt overwhelmed by dealing with them.

Making the hazard visible and realistic: the relationship between flood experience, risk perception, and protective behaviour

We find that people who have reported more experienced flood events are more likely to perceive flooding as a threat, to fear future floods, and to expect them to be severe. The same counts for people who reported to have lost control during the last flood event.

“[…] past experiences are tagged with affect and […] people

automatically recall and draw on these affective associations when judging a future risk […]”

Demuth et al.(2016)

What do these findings tell us about the connection between changing occurrences of flooding and people’s protective behaviour?

We find that people who have reported more numbers of experienced flood events are more likely to undertake protective measures. This could be partially explained by the increased risk perception of the more experienced.

The link between loss of control experience and protective behaviour does not follow such a clear pattern. Apparently, for some respondents, that feeling does result in more protective actions, whereas for others, the opposite is true. Understanding how, why, and for whom affects are linked to behaviour is a research question we want to follow up on.

Learning, designation, or acquiring best practices: the relationship between flood experience, coping appraisal, and protective behaviour

We find that people who have experienced more flood events and a higher degree of loss of control during the last flood experience associate the uptake of protective measures with greater effort. Moreover, loss of control experience is linked to lower perceived self-efficacy in dealing with future floods. Surprisingly, it is also associated with a higher belief in the effectiveness of protective measures.

Again, what do these findings tell us about the connection between changing occurrences of flooding and people’s protective behaviour?

“Thank you for your activities”; a surveyed person thanks the team for their work (photo credit: Sungju Han)

People who associate a greater effort with undertaking protective measures and have a lower perceived self-efficacy are less likely to implement these. Therefore, frequent flooding and loss of control experience may harm the uptake of protective measures. The changing occurrences of floods further exacerbate these effects, as people who have experienced more floods also reported higher levels of perceived loss of control. Since studies have found that coping appraisal is an essential driver of protective behaviour, these results have important implications for disaster risk reduction.

“Having a new experience could thus be defined as an awareness of experiencing, from which our capabilities for understanding and acting in the world may develop.”

Jantzen (2013)

Adding a timely perspective: development of the relationships between risk perception, coping appraisal, and protection motivation over time

Existing studies find that risk perception decreases with time after a hazardous event. In our study, we were interested in how time passing by changes the relationship between personal flood experience, risk perception, coping appraisal, and protective behaviour.

We find only one hint that the influence of time may exist. The strongest link between perceived loss of control and risk perception exists for people whose last flood experience was the most recent. In other words, people who had their last flood event within the last two years are more likely to translate high perceived levels of loss of control into higher risk perception than people whose last flood experience is further away but have reported similar levels of loss of control.

Do not ignore: there is value in looking at the relationships that have been found to be non-significant

Some of the relationships we looked at were not statistically significant, meaning the effects varied widely among individuals. For example, frequent flood experiences increased perceived coping abilities for some people but decreased them for others. We believe that getting a better idea of why frequent flood experiences are a positive driver of coping appraisal and for whom it has the opposite effect is essential to tackle future challenges in light of changing flood frequencies. The same counts for the relationship between loss of control experience and the uptake of protective measures. To increase our ability to understand and better predict people’s behaviour, we need a better grasp of the underlying dynamics that influence the directions of these relationships.

Moving forward: how to enhance our knowledge of the role played by personal hazard experience

First, our findings on the relationship between coping appraisals and flood experience open up new questions. As coping appraisals play a fundamental role in individual behavioural change, we believe that getting further insights here would benefit the design of efficient disaster risk reduction strategies. For this, we propose to get more social science researchers, especially psychologists and sociologists, involved in the research domain. The combined expertise of geographers, psychologists, and sociologists could reveal relationships that remain hidden if these questions are tried to be answered from only one research angle.

Second, we need more experimental studies to understand better how experience shapes behaviour and to make causal interpretations. The same counts for collecting longitudinal data, following the same people over extended periods. This would allow us to better distinguish between the influences of several factors, filter out their particular effect, and get a clearer idea of under which conditions our assumptions apply.

Third, on a personal note, there could be value in expanding the group of collaborators to neuroscientists. Questionnaires always come with the problem of high levels of subjectivity, which we have learned to cope with and interpret our results accordingly. However, we know that assessing brain activity can help us to better understand neurological and cognitive processes underlying people’s behaviour. Understanding what happens in the brain when people are confronted with natural hazards, for example, through serious gaming, could equip us with more ideas on what dynamics may exist and which research questions need to be raised.

References

[1] IPCC. (2023). Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]

[2] Rogers, R. W. (1975). A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114.

[3] Siedschlag, D., Kuhlicke, C., Köhler, S., Masson, T., Bamberg, S., Olfert, A., … & Barth, M. (2023). Risikokommunikation zur Stärkung privater Eigenvorsorge, Abschlussbericht des Vorhabens “Analyse und Anwendung innovativer Instrumente der Steuerung und Kommunikation zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel”, Umweltbundesamt, 1–225.

[4] GeoSN – Landesamt für Geobasisinformation Sachsen, Downloadbereich Ortsteile, 2024.

[5] Geofabrik, Sachsen, 2024.

[6] LUIS – Landwirtschaft- und Umweltinformationssystem für Geodaten. (2024). Gewässernetz (Fließgewässer und Standgewässer).

[7] Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Lazo, J. K., & Trumbo, C. (2016). The effects of past hurricane experiences on evacuation intentions through risk perception and efficacy beliefs: A mediation analysis. Weather, Climate, and Society, 8(4), 327–344.

[8] Jantzen, C. (2013). Experiencing and experiences: A psychological framework. Handbook on the Experience Economy, May, 146–170.

Post edited by Paulo Hader and Asimina Voskaki