How much we pay, as both scientists and the public, for publishing and accessing papers is a hot topic right across the academic community – and rightly so. Publishing houses, and their fees, are big, big business. To which journal we should submit our work is a regular decision we face. But what are the Green, Golden or Hybrid roads? How do pre- and post-prints fit into the journey? In this week’s GD blog post, Martina Ulvrova (Marie Skłodowska Curie Research Fellow, ETH Zürich) shares some of the background, considerations, and discussions surrounding some of the topics surrounding publishing open access. Which road will you take?

Imagine that you just uncovered some exciting results and you want to publish them. But where? Which journal should you consider? What are the best peer-reviewed options right now to not only disseminate scientific research to your peers but also disseminate science to a larger audience? How much are you, as a publishing scientist, willing to pay for this, and how much should the community in turn be expected to pay to read your results?

First, let’s take a look at how publishing traditionally works. The standard publishing model could be considered a genius business model. Why ‘genius’? Well, scientists send papers to journals without being rewarded. Forget about any honorarium for your new discovery. In addition, most journals in the arena charge you a publication fee once your paper is accepted. From the other side, members of the scientific community have reviewed the submitted publications and assessed the novelty of the research. This is also being done without any honorarium.

The remaining piece for the publishing houses is to decide to whom should they sell the publications to? Here again, the scientific community enters a game that is controlled by the publishers. In today’s scientific and publishing climate, an individual scientist’s career heavily depends on the number of publications that they produce. And in turn, to undertake and publish a study, you need to have access to existing publications across numerous journals. Scientists are a perfect market to sell the publications, that were produced more-or-less for free and on a voluntary basis, to. Universities and research institutions pay subscriptions to journals. And the subscription fees are anything but low. One of the biggest publishing groups, Elsevier, reported a profit over 1 billion euros in 2017, and thus paying millions of euros in dividends to its shareholders. Something seems wrong here, doesn’t it? Indeed, the scientific community at-large is starting to wake up and demand changes. The big question is how to change the existing embedded system and from where should this change come? In addition to these questions, a critical unknown here is: are we, as a scientific community, ready for that change?

One of the problematic sides of the whole publishing wheel is that universities pay loads of money to access published papers. This has been controversial for a long time. Indeed, it does not seem right that researchers (and the public) have to buy what they contributed to produce, and furthermore, researcher salaries often come from public money. Instead, research that is a product of public money should be open to everyone since we all pay taxes. Based on similar arguments, huge funding agencies including the European Commission and the European Research Council (ERC) launched Plan S in 2018. Plan S is an initiative with the aim to make publications open access. This means that all publications that are the fruit of public resources should be accessible to anyone without a paywall. This free and open access path will be obligatory for EU funded projects starting as early as 2021. That sounds like a great step that is already happening – but what does it mean exactly to publish open access (OA)? And how can you publish OA?

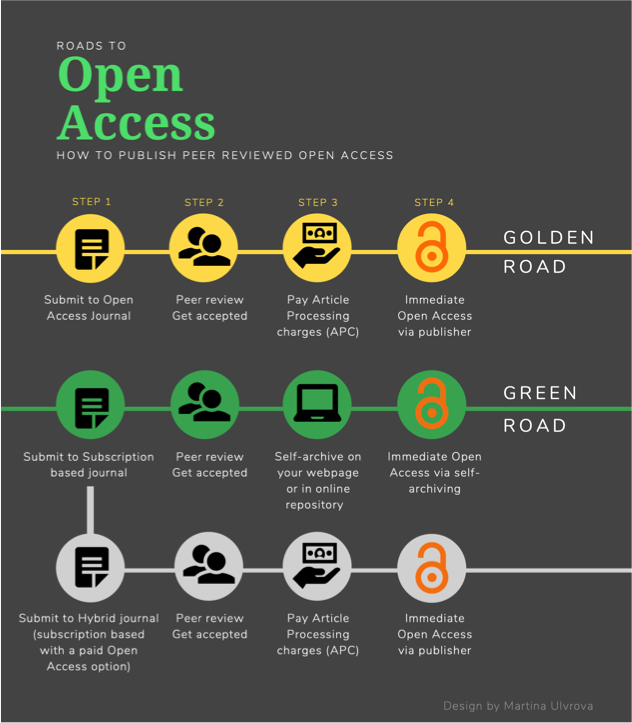

There are two main roads that researchers can take that lead them to an OA publication. First one is a so-called Golden Road. On this path, the researchers submit their paper to an Open Access Journal. The paper goes through peer review and once it is accepted, all rights stay with the authors (or their institution). Often, there are Article Processing Charges (APC) on the golden road. A published paper is accessible to everyone immediately, under the CC-license and reuse is possible. For the geodynamics community, an interesting OA journal is Solid Earth that was established in 2010 by the European Geosciences Union and is published by Copernicus Publications. Slowly but surely it is gaining popularity, and this in turn indicates that the scientific community needs and is willing to turn to OA. APC for Solid Earth are around 80 EUR per journal page. Nature Publishing Group started their OA journal, Nature Communications, in 2010 with APC €4,290 per manuscript. Similarly, the AAAS that is behind Science, launched OA journal Science Advances. In this case, be prepared to pay APC of USD 4500, excluding taxes.

Another path that a scientist can take is called a Green Road. In this case, a manuscript is submitted to a subscription-based journal. It goes through peer review and once it is accepted, all rights are transferred to the publisher. (Side-note: there still might be publication fees, but they are usually much lower than APC OA publishing). Publication is then accessible to the audience via a paywall. This is problematic especially for small institutions that can only afford to pay subscriptions to a limited number of journals. It is also problematic for universities from developing countries that in general operate with lower budget. However, some publishers, including Elsevier, allow self-archiving post-print. By self-archiving I mean that you publish a post-print on your webpage or blog. Some journals also allow the publication of the post-print in a public repository. By post-print I mean the version of the manuscript that went all the way through the peer review (and it equally includes changes suggested by reviewers), but without any copy-editing or formatting by the journal. This is the Green Road. In addition, some subscription-based journals including, for example, Earth and Planetary Science Letters (EPSL) by Elsevier offer a paid open access option. These are so-called hybrid journals. At EPSL, authors can choose to publish OA for USD 3200, excluding taxes.

Whatever the road you choose that leads you to a polished peer-reviewed publication, you can always put online pre-print of your manuscript, i.e. a version of your paper that precedes any peer reviewing and typesetting. The best way is to use one of the existing repositories that are out there. Since 1991, ArXiv has existed for the STEM community, and boasts a submission rate that reached more than (an incredible!) 10,000 papers per month. For the geoscience community, we have EarthArXiv devoted to collecting and hosting papers with Earth and planetary related topics. It just celebrated its second birthday in October of this year. It assures rapid communication of your findings and accelerates the research process. And it accepts both pre-and post-prints.

Why should you care about OA? As I said above, one of the most important aspects of OA publishing is that it is free of charge for readers. This means that you can attract a larger audience; not only is your science read by more people, it may also potentially receive more citations. This increases both your professional and institution’s visibility, and leads to lots of flow-on effects. This is especially important when you are an early career researcher; you want your research to be read and shared as quickly, easily, and as widely as possible. It is also very convenient to be accessing published manuscripts and data without any paywall. A big motivation to publish OA might also be that you do not agree with the current business model of big publishing houses and want to make an affirmative action of change. If you believe that the strategy of publishing houses is outdated and that libraries pay too much, you might want to consider an OA road.

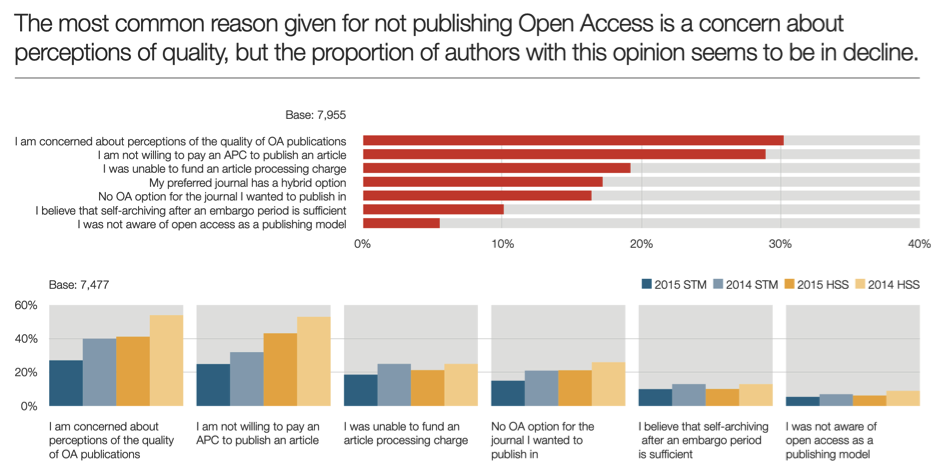

Reasons for not publishing OA? From the Author Insights Survey in 2015, run by Nature Publishing Group

Of course there are still some cons of OA publishing including that the costs for the authors can be exorbitant, up to more than 4000 EUR. Unfortunately, here again, most disadvantaged institutions are small universities and universities located in countries with lower money at hand.

Another big issue is how to guarantee the quality of OA publications? Indeed, as shown in a survey of the Nature Publishing Group from 2015 on the attitude of researchers towards OA publishing, a journal’s reputation (specifically its impact factor) is one of the most important factors that influences the choice of where to submit. The most common reason for not publishing in OA journals is that researchers are concerned about perceptions of the quality of the OA publications. However, this is improving and many OA journals are starting to gain a good reputation. This is something that we, as a community, can largely influence. If we send high quality papers to OA journals and cite OA publications, the OA journals will become higher rated and more attractive. Moreover, the publishing houses of the most prestigious journals have finally started to adapt and created the OA journals, e.g. Nature Communications or Science Advances.

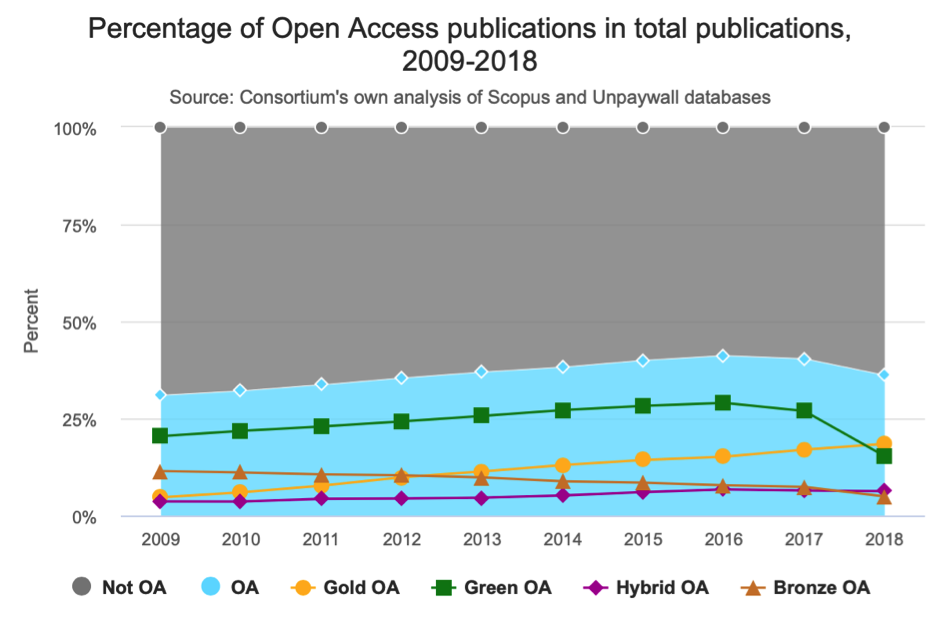

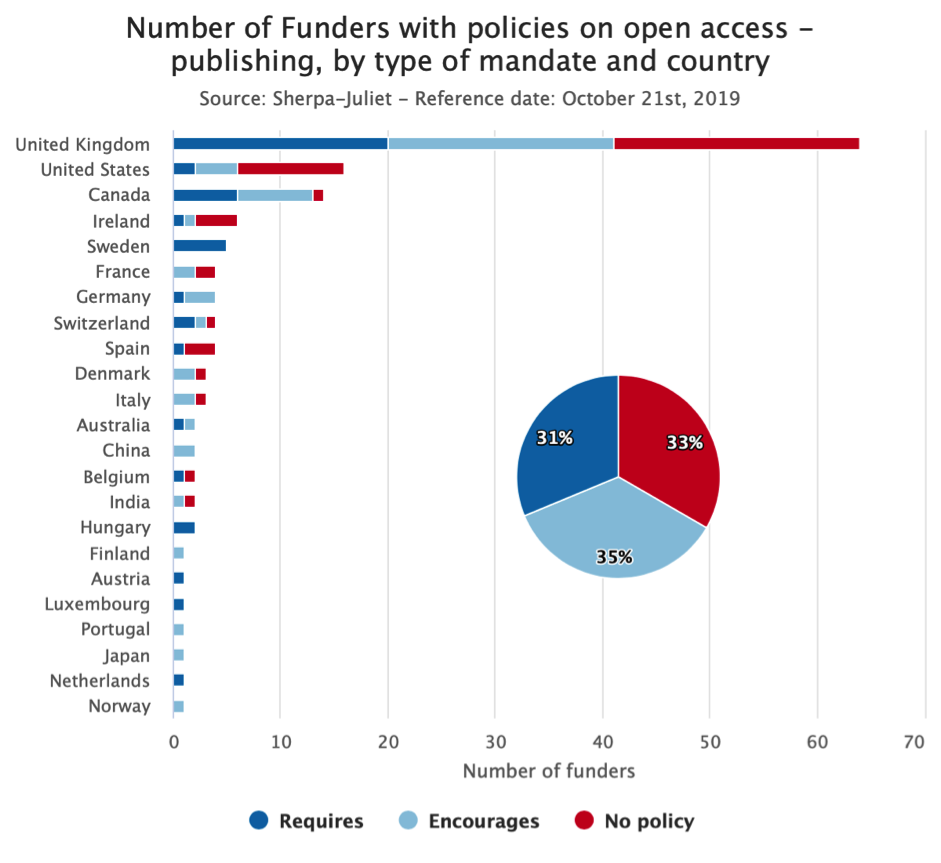

OA publishing has been debated for more than a decade, so where do we stand at the moment? According to the data published by the European Commission, the percentage of OA publications increased from 31% in 2009 to only 36.2% in 2018 (side note: in Earth and related environmental sciences, around 34% of publications were published OA for this period). The United Kingdom, Switzerland and Croatia belong to the countries with the highest proportion of OA publications (slightly higher than 50%). In the meantime, 33% of funding agencies worldwide do not have OA policy, 35% of them encourage OA publishing, while 31% requires OA. These numbers indicate that the system is changing, but it is changing (too) slowly. Current publishing and reading practices are deeply rooted and more action is needed.

The motivation to change the publishing system and make OA common practice should come from the top, i.e. directed by the funder policy, but also (and more importantly) from the bottom, i.e. from the scientific community. Although the system is complex, the urge to replace the outdated system is present. European agencies have launched a pioneering initiative Plan S to publish OA manuscripts as soon as by 2021 (in Switzerland all scholarly publications funded by public money should be OA by 2024). Although no one knows how we will get there, and which rules should we set, it is worth following the OA road. Let’s explore what works best for the scientific community, that will ultimately result in a sustainable, flourishing, and fair publishing environment. Before that, there is always SciHub to get around the existing paywall if needed. Obviously, a legal road is the preferred one and hopefully it is only a matter of time when we will get on that road. And the sooner the better.

This is a huge topic of discussion and comments are welcome below. Further thoughts on Plan S in more details, how it evolves, how it is perceived by the community? Parasite journals? How to assess scientific quality based on something else than the number of publications (e.g. Dora)? Or get in touch if you would like to write an entry for us on the GD Blog!