Mathematics is certainly not every scientist’s cup of tea. Despite the latter, they are, for the most part, very important, since most problems, regardless of their complexity, start and end with a mathematical equation (or set of equations). In this week’s blog, Dimitrios Papadomarkakis (student at the National Technical University of Athens), discusses the subject of closed-form (analytical) solutions in Geodynamics. Specifically, the ever-lasting question on whether they are insightful or detrimental nowadays with the rapid development of Geodynamic numerical codes.

The false dichotomy between closed-form solutions and numerical methods

First things first: what are closed-form analytical solutions? Traditionally, closed-form solutions (a.k.a., closed-form formulae) are considered exact formulas (i.e., equations/relations) that can solve a particular problem that has some specific boundary conditions (boundary conditions serve as constrains to the particular problem at hand). For instance, a cantilever beam has one end free (i.e., the boundary conditions require free shear stress and bending moment) while the other end is fixed at the wall (i.e., the boundary conditions demand zero deflections). Anyhow, for different geodynamic problems, these solutions are usually derived by using one or several mathematical methods. For example, most plane elasticity problems (which are boundary value problems, i.e., problems with specific boundary conditions) rely on complex variable theory, a branch of mathematics that studies functions whose inputs and outputs are complex numbers; some viscoelastic problems can be solved by utilizing the Laplace transform, an algebraic tool that makes equations much easier to solve. From this you can start to see that in order to deduct a closed-form solution, we need a very strong theoretical background of various fields of mathematics.

Nowadays, the rapid development of numerical codes (e.g., finite elements, finite differences), that can model accurately very complex problems has led many scientists to label closed-form solutions as ‘’detrimental’’, since they usually rely on many simplifications which makes models less realistic (e.g., that the media is isotropic and homogeneous, that the response of materials is ideally plastic, etc.). Moreover, the analytical solution route (in comparison with the numerical one) becomes even more cumbersome when the required time and effort that is needed to derive it is also considered. Although the previous arguments are indeed true, they do not, in any way, depreciate the ‘’value’’ of a closed-form solution. Specifically, Carranza-Torres and Fairhust (1999) addressed these concerns arguing that despite numerical codes holding a greater realism over a classical solution, deriving closed-form solutions can provide useful insights for the given problem, such as the influence of each of the variables involved. Further, although they recognize that some degree of simplification is required to deduct the classical solution, it can serve as a correctness check of the numerical analysis wherever it is feasible (Carranza-Torres and Fairhust 1999). Overall, the two methods are not substitutes for each other. They are complementary.

Using analytical solutions to solve geodynamic problems

Now let’s go back to the subject of Geodynamics, which is, undoubtably, a field that has witnessed tremendous growth over the past 60 years, when the theory of plate tectonics started to take shape. The range of geodynamic processes is vast: from gravitational instabilities (i.e., salt tectonics), fluid dynamics (i.e., interaction between hot viscous mantle and subduction plate) to rock rheology (i.e., mantle flow) and more. These are truly complex problems to accurately model and require scientists from different backgrounds. Due to the latter, geodynamic phenomena are mostly modeled through numerical codes that usually apply thermo-viscoelastoplastic constitutive equations (for more information on rock rheology one may read my past blog on the matter). Adding to this, we are witnessing the swift progression of computational capabilities which allows for larger domain areas and longer simulation times to be modelled, going from 2D to 3D. Therefore, in the midst of this full transition from 2-D numerical simulations to 3-D ones, should anyone be concerned with the old school route of closed-form solutions?

We cannot answer the previous question, of course, through a simple yes or no response. Many scientists may rush to a response favoring the numerical direction over the analytical one, because they may believe that the required simplifications comprise the problem’s realism. However, if the assumptions are picked with caution and strategy, this will not be the case whatsoever. In the following, I will give some examples from well-known studies to showcase the valuable resources of analytical solutions.

A strangling slab

Schmalholz (2011), provided a closed-form solution for the complex problem of slab detachment. He argued that the aforesaid process is driven, to some extent, by a process called “necking ’’. The problem was studied by modeling how a thick layer thins and stretches under its own buoyant force, assuming the material flows according to a power-law rule. For this, several simplifications were assumed, including a constant layer length, zero shear stress, and stress-free layer surfaces. Ultimately, the closed-form formulae predicted the so-called thinning factor (i.e., the ratio of the current to the initial layer thickness). The author verified his results against a 2-D finite element thermo-mechanical numerical code, and ultimately showed that the two solutions display reasonable agreement. The advantage of the analytical solution, in the present case, is that the influence of the controlling parameters of the detachment (i.e., the strength of the slab and its rheological properties) are more easily understood.

Gravity falls: Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities

Kaus and Becker (2007), studied the effects of elasticity on large-scale geodynamic processes, such as the development of Rayleigh-Taylor gravitational instabilities. Specifically, they analysed the problem by deriving closed-form formulae, as well as a semi-analytical solution (these solutions combine both analytical formulation and numerical analysis to obtain the final solution), and verified the results of both against a 2-D finite element viscoelastoplastic numerical code. To deduct the analytical solution, they assumed a viscoelastic layer, that represented the lithosphere, overlying an infinitely viscous half-space. The authors considered two main assumptions: (a) the amplitudes of the instability were small, (b) no advection and rotation of stresses took place. Both the semi-analytical, as well as the analytical, solutions showed good agreement with the numerical results for finite amplitudes. The advantage of the closed-form solution (and even the semi-analytical one) lies in the fact that it is extremely difficult to differentiate the contributions of different effects (e.g., plastic deformations from elastic ones) in a numerical analysis where a viscoelastoplastic rheology is used.

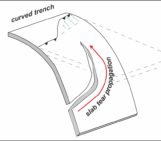

Initiating subduction

More recently, Li and Gurnis (2023) gave a closed-form solution for the everlasting conundrum of the initiation of subduction, basing their analysis on how forces are balanced in subduction zones. The results of their somewhat simplified model were compared with those of a 2-D finite element viscoplastic and viscoelastoplastic numerical code, respectively. Despite the assumptions of the authors, the analytical solution displayed very close agreement with the numerical codes, especially in terms of the time and total work to initiate the subduction, as well as the force and velocity as a function of the convergence and time. In this instance, the closed-form solution can help to interpret the complicated process of subduction initiation, due to its straight forwardness, in contrast to the numerical simulations which can often produce ‘’untraceable’’ results that are hard to interpret.

Bringing the analytical and numerical worlds together

The aim of this blog post was to showcase that closed-form solutions are under no circumstance detrimental in modern day geodynamics, where 2-D and 3-D numerical simulations are for the most part the go-to solution. On the contrary, I briefly showed through the above three examples that they can be viable solutions that can provide valuable insights to very complex processes. Finally, they can also be coupled with experimental modeling (e.g., analogue modeling), in an attempt to further strengthen their results and also test the validity of the presumed assumptions.

What do you think is the future of closed-form solutions in Geodynamics? Do you have any other examples? Let us know in the comments!

References Carranza-Torres C, Fairhurst C (1999) The elastoplastic response of underground excavations in rock masses that satisfy the Hoek-Brown criterion. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 36(6): 777-809. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(99)00047-9 Kaus BJP, Becker TW (2007) Effects of elasticity on the Rayleigh-Taylor instability: implications for large-scale geodynamics. Geophysical Journal International 168(2): 843-862. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03201.x Li Y, Gurnis M (2023) A simple force balance model of subduction initiation. Geophysical Journal International 232(1): 128-146. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggac332 Schmalholz SM (2011) A simple analytical solution for slab detachment. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 304(1-2): 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.01.011