This week on the EGU GD Blog, we interview the newly elected incoming Geodynamics Division President, Jeroen van Hunen (Durham University). Jeroen takes on the role for 2021-2023, from Paul Tackley (ETH Zürich). Jeroen is a Professor within the Department of Geosciences, including the Geodynamics, Geophysics, and The Solid Earth research groups. He is originally from the Netherlands, having studied at Utrecht University, then has been located at University of Colorado at Boulder, ETH Zürich, before settling in Durham.

Meet Jeroen van Hunen, the GD President (2020-2022)

Can you please tell us a bit about your research?

I started my career in subduction modelling (shallow flat subduction, e.g. under South America today, or North America in the past), as a PhD student. As postdoc I started working on other topics, e.g. mantle plumes and small-scale convection. After that I got interested in continental collision processes. But I was always fascinated by early Earth dynamics, and this is what I like to work on mostly: given the relative sparsity of data on that topic, it frequently involves neighbouring disciplines, such as early life, planetary dynamics, or atmospheric science: that makes it an interesting topic to work on or organise EGU sessions about.

What drew you to a career in the natural sciences, and geodynamics in particular?

I started off studying physics, but quickly realised that GEOphysics meant this could be combined with being outdoors sometimes, and attending field excursions. I always liked computer programming, so when I had to choose a specialisation, I chose geodynamics over field geophysics.

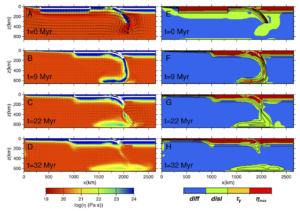

Models of continental collision and subsequent slab break-off, from van Hunen and Allen (2011) EPSL

Did you always see yourself staying in academia?

No, I think that just happened: when I finished my MSc, my supervisor offered me a PhD position. After that I managed to find an interesting postdoc position, and so on. So really, from one thing came the other. But perhaps I always wanted to stay in academia. Particularly the prospect of teaching at Universities attracted me (and still does).

I see you are also interested in geothermal and carbon capture research (e.g. the Heat Beneath our Feet), how did you get into that?

I guess that is for two reasons. Attracting funding is always an issue, and perhaps particularly so for blue-skies research without direct industrial or societal impact like geodynamics. So trying to tap into industrial funding helps a bit. But I also find it satisfying somehow to work on something that has more immediate impact, and with more practical use. E.g. both carbon capture and geothermal research directly aim at solutions to reduce our carbon footprint. But I think my core interest will always be in geodynamics.

You’re also the Director of Postgraduate Studies at the Department of Geosciences – that must be a significant responsibility. How do you best manage your time between research, teaching, administration, outreach, … and your spare time?

I handed over that task to a colleague recently. But time seems to be my worst enemy always: there is never enough time to do all the things I want to do. I’d love to say that I have a grand plan to manage my time, but I don’t. Often I end up doing what is most urgent rather than what is most important, so spare time seems permanently unavailable.

You’ve been living in Durham for 14 years, and counting. What are your favourite aspects about living there?

So many aspects: Durham University is a great place to work. Things can always be improved, of course, but overall, everything works quite fairly smoothly, with a comparatively flat organisational structure, and the general atmosphere is informal and positive. Durham itself is small (~50,000 people only) and pretty (with a castle and a world-heritage cathedral), and is a very pleasant town to be in, especially when the weather is nice. I feel surrounded by warm, friendly and relaxed people and nice rural countryside, and I can bike to work. After 14 years of living here, it really became my home.

View of Durham Cathedral. Image by jimsumo999 from Pixabay

What has been the biggest struggle and the biggest opportunity that quarantine conditions over the last 2+ months for you?

The administrative workload definitely went up, with discussions about and preparations for online teaching and exams. But I also feel more in control over how to fill in my working day since the lockdown: if I can I’ll switch off email, and can work undisturbed on something. And I am seeing my wife and daughters more often, which is a big plus.

What did you think of this year’s online EGU experience?

I missed the face-to-face contact, which helps getting good discussions going and set up new collaborations. But I didn’t miss the travelling and spending time in a boring hotel room. I think EGU Online worked surprisingly well. It took me a lot of time to prepare well for a session, so in the end I didn’t manage to attend as many as I would have liked.

But regardless of whether we liked the online EGU or not, I think travelling across the globe to have face-to-face chats about science is something we sadly may not be able to afford for much longer for environmental reasons. The amount of CO2 we collectively managed to keep out of the atmosphere for this year’s EGU by not travelling to Vienna is enormous, and online conferences will, in my view, have to become part of our lives.

Do you have any specific plans or upcoming developments for the GD division during your term?

I think I am lucky to inherit a healthy GD division from Paul Tackley to start with. But an increasing threat for the division is the ever-decreasing level of blue-skies funding. Promoting the typically fundamental research in geodynamics will be essential. This EGU GD blog is a brilliant example of how to do this. Other opportunities could be encouraging outreach activities for the general public and schools, or dialogues with governing and funding bodies. A task at the top of my agenda will be to make sure that GD will continue to thrive in future online environments: this is an opportunity for us to attract more participants from around the world. GD is also the division that has the capacity to link other disciplines together through the community’s strong modelling skills, which we should try to exploit.

Any finally, for our ECR readers in particular, what is the best advice you ever received?

There is a Dutch expression that probably translates best as ‘A bow long bent at last grows weak’, an expression that probably exists in many different languages. It essentially suggests that, in order to get the best results, you have to relax once in a while. Whenever things don’t go as well as I had planned, it is rather comforting to remind myself of this advice.

Jeroen can be reached via: jeroen.van-hunen@durham.ac.uk and he is also on Twitter