Geodynamicists have long grappled with the complexities of Earth’s mantle dynamics—modeling Venus’ interior adds an extra layer of challenge without the benefit of plate tectonics! This week in News & Views, Madeleine Kerr, a PhD candidate from the University of California, San Diego, explores how numerical modeling can shed light on mantle dynamics and the evolution of Earth’s enigmatic twin.

Our macroscopic understanding of Earth’s surface uses the framework of “plate tectonics” to explain spreading ridges, ocean trenches, intraplate volcanism, and earthquakes as a manifestation of a whole-mantle convective dynamics. It is widely understood that Earth is in a mobile lid tectonic regime, and that the largest scale patterns of surface volcanism are associated with plates and plate boundaries. The convective regime for Venus, however, is still a matter of debate. There are a few tectonic models for Venus’s lithosphere: among them are the stagnant lid model [1] where the lithosphere of Venus is strong and rigid due to temperature dependence of viscosity, and also a plutonic “squishy” lid model [2] where intrusive magmatism weakens the lithosphere allowing it to deform more readily. Whether the lithosphere is in a stagnant lid or plutonic squishy lid regime, the question of what convection looks like in the interior remains unanswered.

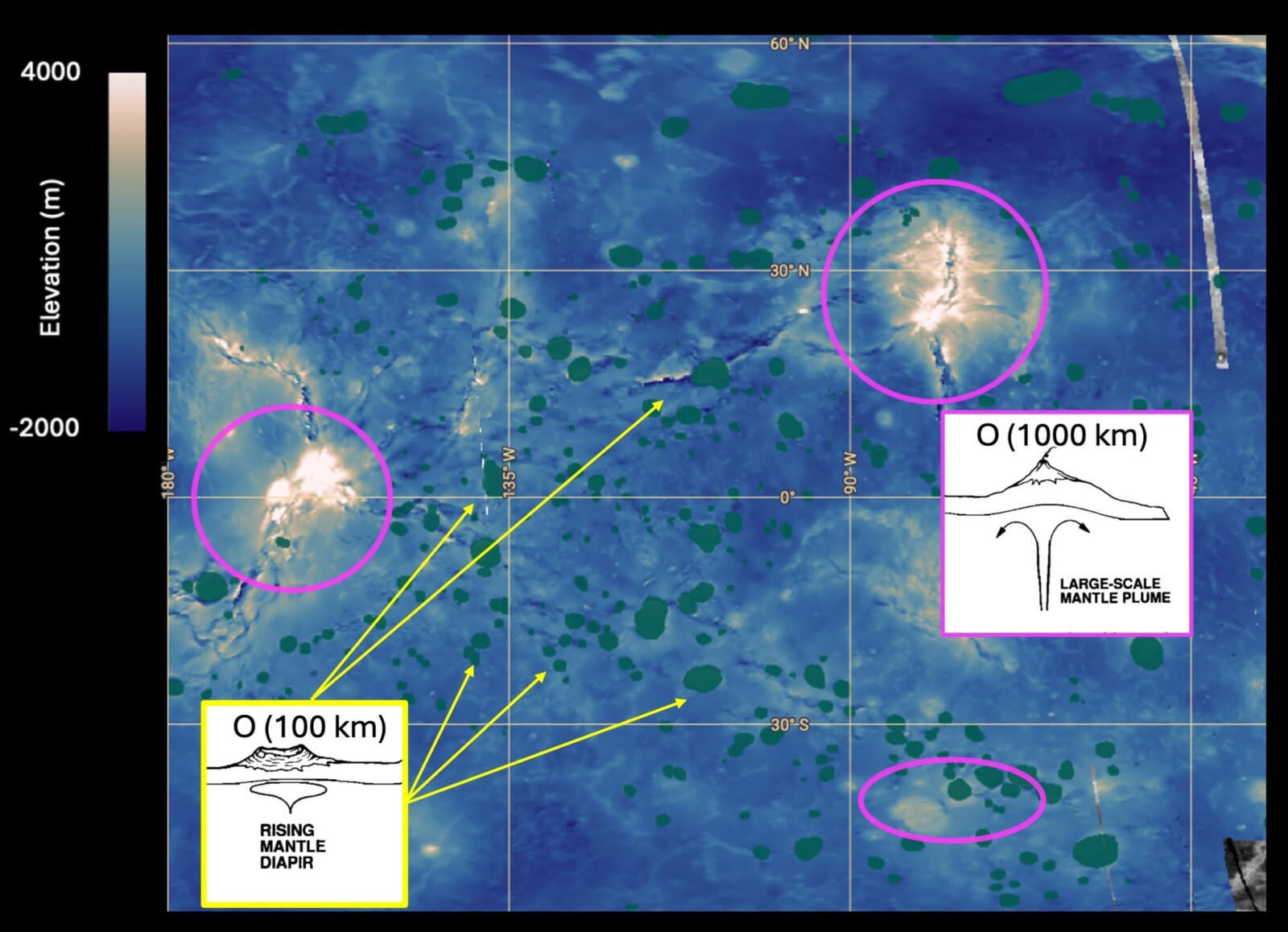

Fig 1: A topographic map of the B.A.T. region where the Beta, Atla and Themis regios are circled in pink. Coronae are highlighted in dark green. The large volcanic rises (pink circles) are thought to form from large ~1000 km plumes and the coronae are thought to form from smaller ~100 km plumes. Topographic map and coronae distributions are from Venus Quickmaps and the cartoons overlaid are from Stofan et. al. (1992).

A particular area of interest on Venus is the B.A.T. region which highlights a so-called paradox in the size of mantle upwellings that can exist on Venus. The large volcanic rises (pink in Fig. 1) are considered to be the surface expression of large-scale mantle plumes (~2000 km in diameter) from the thermal boundary layer at the core mantle boundary [3]. Coronae, which are roughly-annular volcano-tectonic features that are arguably unique to Venus, are also thought to form from both smaller mantle plumes [5] and/or cold drips or delaminations from the base of the lithosphere [6]. Coronae are, on average ~200 km across. and their coexistence in the B.A.T. region with the large volcanic rises poses the question of what type of convective dynamics underneath can create two distinct scales and style of mantle plumes – (1000 km) and (100 km) in the same mantle region simultaneously.

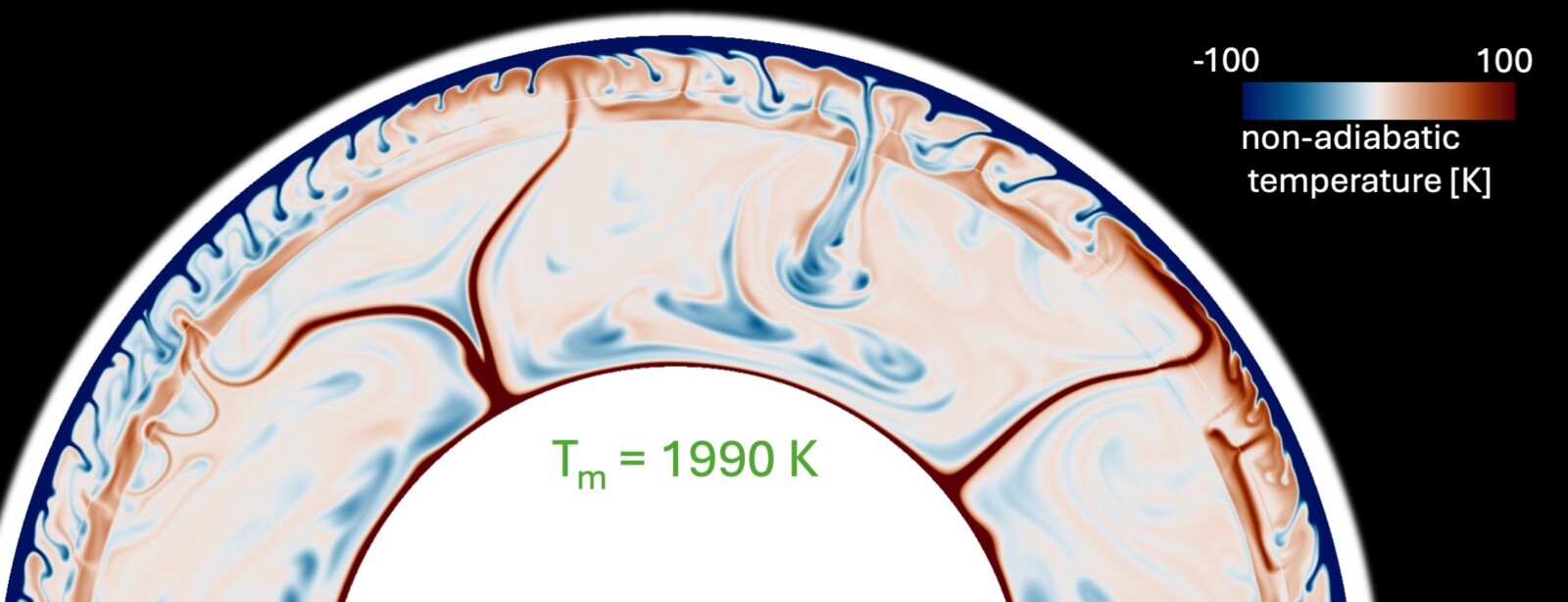

Conceptual models from other researchers had proposed that the abundant secondary plumes which formed coronae were sourced from a shallower thermal boundary layer in the mid-mantle [8]. However, a mechanism for this shallower boundary layer was elusive. Our work looks at how mineral phase transitions for mantles that are hotter than Earth’s (i.e. > 1850 K) provide this missing piece to the puzzle: a layering mechanism which generates an upper mantle convective system with small, cold delaminations and small, hot plumes. We use the geodynamic modeling code ASPECT [9] with the entropy formulation of the energy equation [11] to explore the mantle composition of pyrolite in a simple stagnant lid tectonic regime for mantle temperatures between an Earth-like 1600 K and 2000 K, the upper-most limit of solid-state convection. We found that above 1850 K, the phase transition from Wadsleyite into Majorite + ferropericlase generates a stalling effect on both hot and cold material at ~600 km deep. This ephemeral layering falls apart when perturbations to the stalled layers destabilize it such that large portions of the upper mantle avalanche into the lower mantle, and a return flow of warmer material takes the form of small-scale plumes from the base of the transition zone (Fig. 2).

Fig 2: A snapshot in the steady state evolution of the bottom-heated stagnant lid models showing the characteristic dynamics of the mantle transition zone at 1990 K. As higher mantle temperatures, the adiabat passes further into the high-temperature phase transition of Wadsleyite to Majorite and ferropericlase which is a thin transition at 1700 K, but which becomes thickest at 1900 K, causing the strongest amount of mantle layering. Figures are from Kerr et al. (2025).

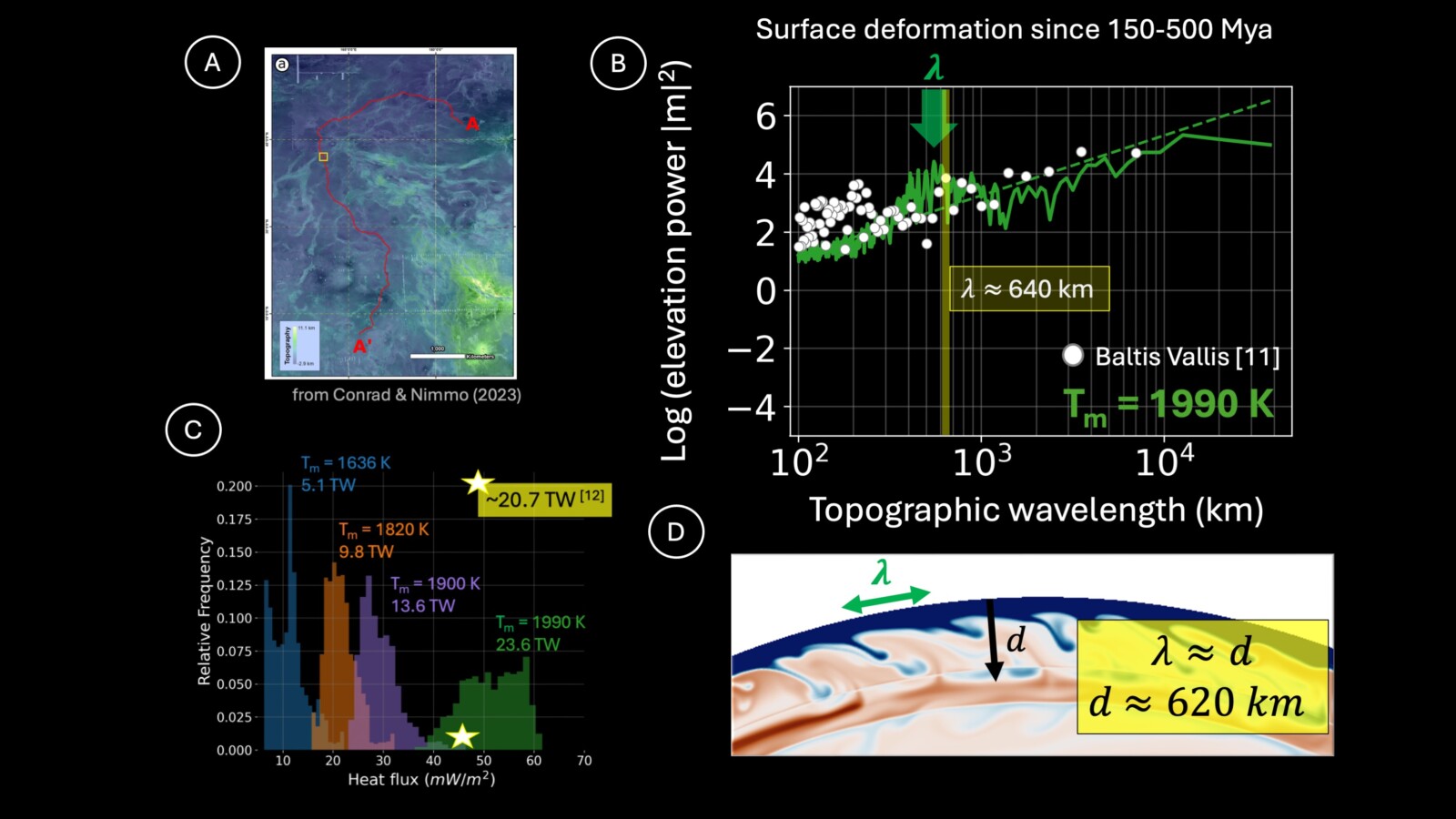

We compare our 2D models to estimates of Venus’s surface heat flow and dynamic topography. As shown in Fig. 3, the 1990 K model snapshot is shifted to higher heat fluxes than one might expect and is also more variable. This foreshadows that the ephemeral layering is changing the Rayleigh-Nusselt scaling, or heat flow efficiency, of the convection. It also shows that the layering introduces global variability in surface heat flow, which is proposed for Venus given the variability of estimates for Venus’s elastic lithosphere thickness [12]. We compare our models’ dynamic topography to the vertical surface deformation that the Baltis Vallis canali, or lava flow channel, has undergone since its emplacement 150-500 Ma [14]. They observed a peak in their spectra at 640 km which they attribute to an “unidentified process.” Our models with temperatures between 1900 K and 2000 K show a peak in the dynamic topography that encompasses the Baltis Vallis 640 km peak. We attribute the 640 km wavelength in Baltis Vallis to wavelength of secondary convection in the upper mantle (i.e. the distance between cold drips and warm plumes or return flows).

Fig 3: (A) is an annotated (text box) figure from Conrad & Nimmo (2023) which shows the extent of the Baltis Vallis canali. In the power spectra plots in (B), the white dots correspond to the surface deformation on Baltis Vallis. The wavelength of 640 km is encompassed by the topographic signature of secondary convection in the upper mantle from our models (D), denoted by the green lambda. (C) A series of histograms showing the distribution of heat flux values for a set of evenly spaced points around the outer boundary of the models. The yellow star represents an estimate for Venus’ heat flow and corresponding mean surface heat flux from elastic lithospheric thickness measurements in Smrekar et al. (2023).

Future directions of this work will investigate further the Rayleigh Nusselt scaling law for ephemerally layered convection which can be used for 1D parameterized models of mantle convection and global heat flow. Additionally, these dynamics will be explored in 3D and with melting to explore resurfacing rates of Venus. Preprint: [link].

References: [1] C. V. Reese et al. Icarus 139, 67-80 (1999). [2] Lourenço et al. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 21, e2019GC008756 (2020). [3] E. R. Stofan, et al. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 100, 23317-23327 (1995). [4] J. Schools, S. E. Smrekar, Earth and Planetary Science Letters 633, 118643 (2024). [5] Piskorz et al. (2014). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 119(12), 2568-2582. [6] E. R. Stofan ,et al. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 97, 13347-13378 (1992). [7] S. E. Smrekar, E. R. Stofan, Icarus 139, 100-115 (1999). [8] Timo Heister, et al. Geophysical Journal International 210 (2) (May 9, 2017): 833–851. [9] J. Dannberg, et al. Geophysical Journal International 231, 1833-1849 (2022). [10] Kerr, M. C., Stegman, D., Smrekar, S. E., & Adams, A. C. (2024). Authorea Preprints. [11] W. Conrad, F. Nimmo, Geophysical Research Letters 50, e2022GL101268 (2023). [12] S. E. Smrekar et al. Nature Geoscience 16,13-18 (2023).