Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Women in science/geodynamics: a topic we have discussed before and should continue to discuss, because we’re not there yet. In this new Wit & Wisdom post, Marie Bocher, postdoc at the Seismology and Wave Physics group of ETH Zürich, discusses a range of all-too-common encounters women face and a possible solution to awareness: comics (drawn by Alice Adenis, PhD student at ENS Lyon).

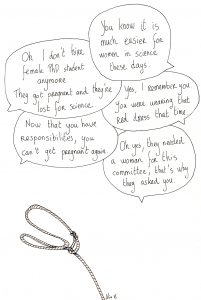

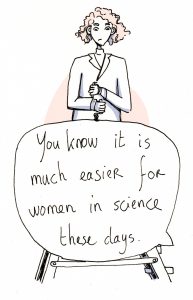

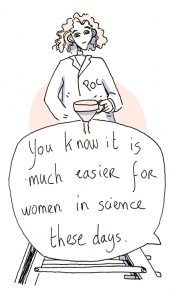

You know it is so much easier for women in science these days

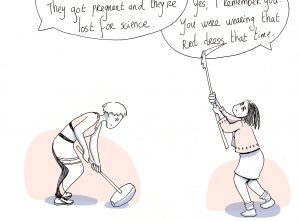

“Oh I don’t hire female PhD students anymore: they get pregnant and then they’re lost for science”

“Yes, I remember you, you were wearing that red dress last time”

“Now that you have responsibilities, you can’t get pregnant again”

Oh, yes, they needed a woman for this committee, that’s why they asked you

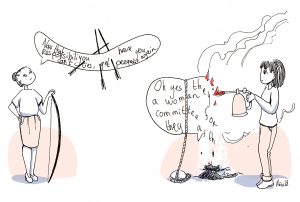

And my two personal favourites:

“You should be happy that someone called you an angel [author’s note: in a professional setting], that means that you are beautiful, what are you complaining about?”

“I do not understand why women need to work, I mean, my wife did a marvelous job raising our children while I was working, I don’t get why this way of life has to change.”

These statements have been heard in real life, in the professional setting of the research lab (or at a conference), and were directed towards real humans, who share the particularity of being both women and Earth scientists (I know! Crazy, right?). If you have said similar things or think that some (or all) of these sentences are not that big of a deal, please go to the end of this article: I have a small text just for you! Anyway, I am pretty sure I’m not the only one to find this type of comments disturbing, to say the least. And I want to do something about it.

One of the first steps in the fight against sexism is to identify and describe the various ways it is expressed in our community. Research in geodynamics is definitely international, and patriarchy comes in different flavours all around the world. Each lab has its own blend of cultures and individuals that leads to different climates. That is also true for conferences and other events. As a result, the experience of working as a female in academia and developing as a scientist varies.

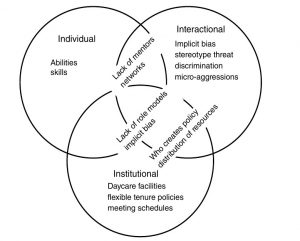

However, the patriarchal power structures and strategies are similar, even if the degree to which those are expressed in a specific setting varies. Here is a diagram that, I think, sums up the variety of barriers to gender equality we face in academia pretty well:

The sentences I quoted in the beginning of the article, and illustrated by Alice Adenis throughout this post, are examples of sexist microaggressions (look up the interactional circle in the diagram!). Generally speaking, microaggressions are, according to Derald Wing Sue (2010), “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership”. In the context of sexism, they remind women of the stereotypical roles society has assigned to them: we should be pleasant to the eye; our most important achievement should be to become a mother; we are not as competent as men in science, and therefore any attempt to reach parity in committees means that women are helped or preferred over more competent men… Taken individually, and depending on the person they are addressed to, they go unnoticed, they are annoying, or they are deeply hurtful. Put together and accumulated over time, they create a chilly climate for women in academia and contribute to discourage young female researchers to pursue an academic career.

These sexist microaggressions are the subject of an initiative to which I contribute, together with Alice Adenis, Claire Mallard, Maëlis Arnould, Martina Ulvrova, Mélanie Gérault and Nicolas Coltice: the project “did this really happen?!“. We gather testimonies of everyday sexism in academia, translate them into comics, and publish them on this blog. The aim is to show the nature of current everyday sexism in academia, to make it visible to people who do not see it, and to start a conversation in our community on how we can do better, be more inclusive and more respectful of each other. To achieve this goal, we need you, dear reader. You want to contribute? Here is what you can do:

• Enjoy reading the comics, and think about how you would have reacted in such situations

• Share the contents of the website on your favorite social media

• Print some comics and put them in the common room of your lab to start discussions

• Share one of your personal stories with us, anonymously or not, through this form

Finally, you can join the course on unconscious bias and the session on ‘promoting and supporting equality of opportunities in geosciences’ of the next EGU general assembly in Vienna!

Hope to see you there!

A text to those who do not see why I ‘make such a fuss’ about some people sometimes saying stuff which are ‘maybe a bit sexist’.

You might feel like I’m attacking you. I am not. I’m against sexist behaviour – not against people. I am not fighting against men, I am fighting against patriarchy. I have very rarely encountered profoundly sexist people, and I am convinced that the people who did say the sentences I gave as an example meant no harm. Moreover, I have also said sexist (and racist) stuff and will probably say more in the future, because – like the majority of researchers right now – I grew up and live in a white-supremacist and patriarchal society, and this affects my behaviour even if I don’t want to, even if I am a convinced feminist, fighting for a world with more equality.

That being said, here is how I interpret the example sentences and why I think they are not acceptable:

“You know it is so much easier for women in science these days”

This sentence is a classical variation on the concept that women are now favoured over more competent men because of parity issues. While the discrimination against women during the recruitment process has been documented (see for example this article on CV selection, this article on the letter of recommendations, and this article on the same topic), I am still trying to find a study on all these incompetent women who steal the jobs of competent men…

“Oh I don’t hire female PhD students anymore: they get pregnant and then they’re lost for science”

By saying that, you suppose that every woman will systematically want children and renounce her career plans as soon as she becomes a mother. This results in restricting women to only one of the many lives they could choose for themselves. This is also gender discrimination and illegal in a lot of countries.

“Yes, I remember you, you were wearing that red dress last time”

When you say that, you send the message that you are paying more attention to my appearance than to what I have to say. This is objectifying and out of place in a professional setting.

“Now that you have responsibilities, you can’t get pregnant again”

Choosing to have a child or not IS A PERSONAL DECISION. Please do not give your opinion on these matters unless your colleague actually asks for it.

“Oh, yes, they needed a woman for this committee, that’s why they asked you.”

You are implying that I am not competent for this committee, but only selected for my gender. That is insulting.

“You should be happy that someone called you an angel [author’s note: in a professional setting], that means that you are beautiful, what are you complaining about?”

See the red dress remark.

“I do not understand why women need to work, I mean, my wife did a marvelous job raising our children while I was working, I don’t get why this way of life has to change.”

Again, this restricts women into one role, that does not necessarily fit everybody.

References Holmes, M. A. (2015) A Sociological Framework to Address Gender Parity, in Women in the Geosciences: Practical, Positive Practices Toward Parity (eds M. A. Holmes, S. OConnell and K. Dutt), John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ. doi: 10.1002/9781119067573.ch3 Sue, Derald Wing. Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Camille

You know what ? I did not realize until i read your article that i was being discriminated by people from my lab and during congress. I am used to it… So sad…

Lenie Austin

“Oh, yes, they needed a woman for this committee, that’s why they asked you.” This statement is very painful, but if you do your best they well eventually realize that you are not just a girl. You are a girl with skills which some men can’t do.