Carbon dioxide plays a significant role in trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere. The gas is released from human activities like burning fossil fuels, and the concentration of carbon dioxide moves and changes through the seasons. Using observations from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2) satellite, scientists developed a model of the behavior of carbon in the atmosphere from Sept. 1, 2014, to Aug. 31, 2015. Scientists can use models like this one to better understand and predict where concentrations of carbon dioxide could be especially high or low, based on activity on the ground. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/K. Mersmann, M. Radcliff, producers

Drawing inspiration from popular stories on our social media channels, as well as unique and quirky research news, this monthly column aims to bring you the best of the Earth and planetary sciences from around the web.

Major story

Our top pick for October is a late breaking story which made headlines across news channels world-wide. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) announced that ‘Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere had surged to new records’ in 2016.

“Globally averaged concentrations of CO2 reached 403.3 parts per million in 2016, up from 400.00 ppm in 2015 because of a combination of human activities and a strong El Niño event,” reported the WMO in the their press release.

The last time Earth experienced a comparable concentration of CO2 was 3 to 5 million years ago (around the period of the Pliocene Epoch), when temperatures were 2-3°C warmer and sea level was 10-20 meters higher than now. You can put that into context by taking a look at this brief history of Earth’s CO2 .

Rising levels of atmospheric CO2 present a threat to the planet, most notably driving rising global temperatures. The new findings compromise last year’s Paris Climate Accord, where 175 nations agreed to work towards limiting the rise of global temperatures by 1.5 degrees celsius (since pre-industrial levels).

No doubt the issue will be discussed at the upcoming COP 23 (Conference of Parties), which takes place in Bonn from 6th to 17th of November in Bonn. Fiji, a small island nation particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather phenomena (a direct result of climate change), is the meeting organiser.

What you might have missed

The 2017 Hurricane season has been devastating (as we’ve written about on the blog previously), but in a somewhat unexpected turn of events, one of the latest storms to form over the waters of the Atlantic, took a turn towards Europe.

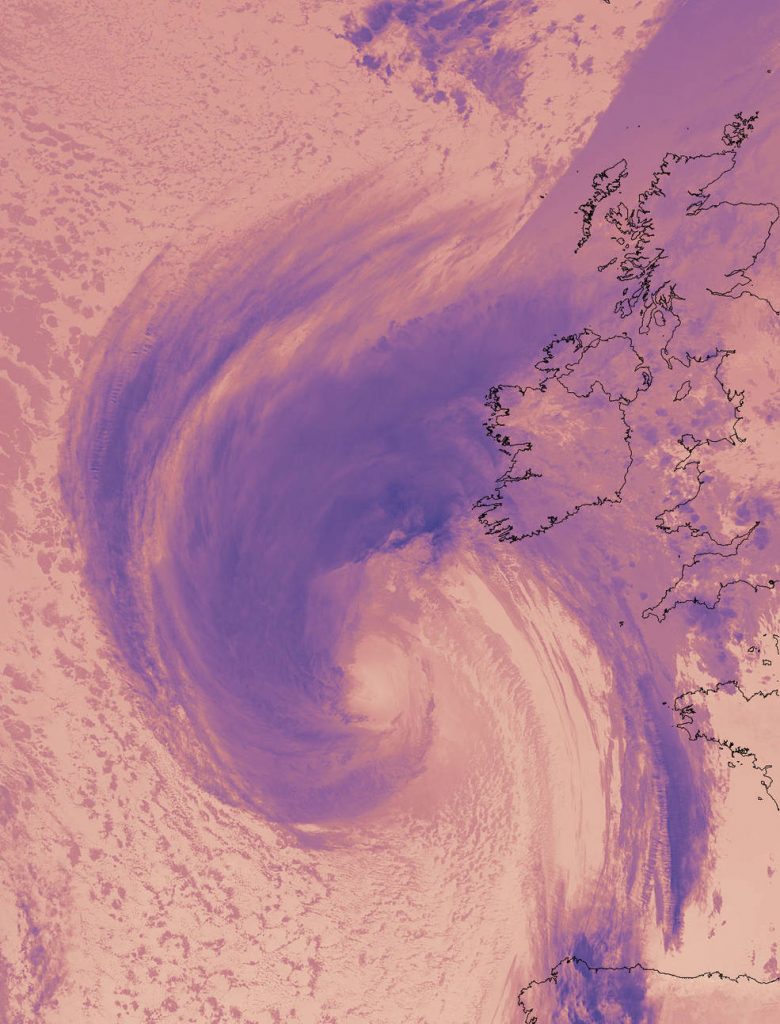

Storm Ophelia formed in waters south-west of the Azores, where the mid-latitude jet stream push the storm toward the UK and Ireland. By the time it made landfall it had been downgraded to a tropical storm, but was still powerful enough to caused severe damage. Ireland, battered by 160 kmph winds, declared a national emergency following the deaths of three people.

NASA-NOAA’s Suomi NPP satellite took this thermal image of Hurricane Ophelia over Ireland on Oct. 16 at 02:54 UTC (Oct. 15 at 10:54 p.m. EDT).

Credits: NOAA/NASA Goddard Rapid Response Team

The effects of the storm weren’t only felt across the UK and Ireland. In the wake of an already destructive summer fire season, October brought further devastating forest fires to the Iberian Peninsula. The blazes claimed 32 victims in Portugal and 5 in Spain. Despite many of the wildfires in Spain thought to have been provoked by humans, Ophelia’s strong winds fanned the fire’s flames, making firefighter’s efforts to control the flames much more difficult.

On 16th October many in the UK woke up to eerie red haze in the sky, which turned the Sun red too. The unusual effect was caused by Ophelia’s winds pulling dust from the Sahara desert northward, as well as debris and smoke from the Iberian wildfires.

And when you thought it wasn’t possible for Ophelia to become more remarkable, it also turns out that it became the 10th storm of 2017 to reach hurricane strength, making this year the fourth on record (and the first in over a century) to hit that milestone.

But extreme weather wasn’t only limited to the UK and Ireland this month. Cyclone Herwart brought powerful winds to Southern Denmark, Germany, Poland, Hungary and Czech Republic over the final weekend of October. Trains were suspended in parts of northern Germany and thousands of Czechs and Poles were left without power. Six people have been reported dead. Hamburg’s inner city area saw significant flooding, while German authorities are closely monitoring the “Glory Amsterdam”, a freighter laden with oil, which ran aground in the North Sea during the storm. A potential oil spillage, if the ship’s hull is damaged, is a chief concern, as it would have dire environmental concerns for the Wadden Sea (protected by UNESCO).

Links we liked

- After more than 15 productive years in orbit, the U.S./German GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) satellite mission has ended science operations

- Is the Arctic’s biggest ice sheet in irreversible meltdown? Much of the data and knowledge gathered to answer that question is a direct result of the data gathered by the GRACE mission, so what happens now the satellite has come to the end of its life?

- Ichthyosaur fossil discovered for first time in India

- Mars class of 2020: A diverse group of missions takes aim at the Red Planet

- Yellowstone spawned twin super-eruptions that altered global climate

The EGU story

This month we released not one but two press releases from research published in our open access journals. The finding of both studies have important societal implications. Take a look at them below

Deforestation linked to palm oil production is making Indonesia warmer

In the past decades, large areas of forest in Sumatra, Indonesia have been replaced by cash crops like oil palm and rubber plantations. New research, published in the European Geosciences Union journal Biogeosciences, shows that these changes in land use increase temperatures in the region. The added warming could affect plants and animals and make parts of the country more vulnerable to wildfires.

Study reveals new threat to the ozone layer

“Ozone depletion is a well-known phenomenon and, thanks to the success of the Montreal Protocol, is widely perceived as a problem solved,” says University of East Anglia’s David Oram. But an international team of researchers, led by Oram, has now found an unexpected, growing danger to the ozone layer from substances not regulated by the treaty. The study is published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, a journal of the European Geosciences Union.