Drawing inspiration from popular stories on our social media channels, as well as unique and quirky research news, this monthly column aims to bring you the best of the Earth and planetary sciences from around the web.

Major Story

This month the Earth science media has directed its attention towards a pacific island with a particularly volcanic condition. The Kilauea Volcano, an active shield volcano on the southeast corner of the Island of Hawai‘i, erupted on 3 May 2018, following a magnitude 5.0 earthquake that struck the region earlier that day.

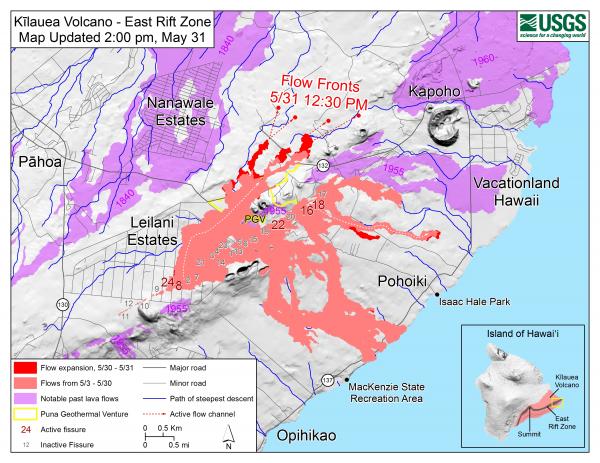

Since the eruption, more than two dozen volcanic fissures have emerged, pouring rivers of lava onto the Earth’s surface and spurting fountains of red-hot molten more than 70 metres into the air. As of today, Kilauea’s eruption has covered about 3534 acres (14.3 square kilometres) of the island in lava, according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s most recent estimates.

The island’s volcanic event has dealt heavy damages to the local community, forcing thousands of locals to evacuate the affected area. On 4 May, the governor of Hawaii, David Ige, declared a local state of emergency, activating military reservists from the National Guard to help with evacuations. Over the month Kilauea’s eruption has engulfed nearby neighborhoods in an oozing layer of lava, overtaking 75 homes, blocking major roads, swallowing up many vehicles, and even briefly threatening a geothermal power plant.

Kilauea’s molten rock, with temperatures at about 1,170 degrees Celsius, is an obvious danger to the local Hawaiian community (one serious injury reported so far). However, the volcanic eruption presents many airborne hazards as well.

In addition to spewing out lava, the Kilauea eruption has projected ballistic blocks, some up to 60 centimeters across, and released clouds of volcanic ash and vog (a volcanic smog of sulfur dioxide and aerosols). The ashfall and gas emissions can create hazardous conditions for travel, produce acid rain as well as cause irritation, headache and respiratory issues.

Kilauea’s lava has steadily marched towards the coast of the Big Island, and recently reached the Pacific Ocean. This interaction of molten rock and ocean water has created plumes of laze (lava haze). Laze is essentially a cloud of acidic steam, mixed with hydrochloric acid and fine particles of volcanic glass. Coming into contact with the toxic vapour can result in eye and skin irritation as well as lung damage.

Map as of 2:00 p.m. HST, May 31, 2018. Given the dynamic nature of Kīlauea’s lower East Rift Zone eruption, with changing vent locations, fissures starting and stopping, and varying rates of lava effusion, map details shown here are accurate as of the date/time noted. Shaded purple areas indicate lava flows erupted in 1840, 1955, 1960, and 2014-2015. (Image: U.S. Geological Survey)

While residents have been fleeing the the Kilauea-affected region, many scientists have rushed to the Big Island to study the eruption. A swarm of researchers have spent the month recording lava flow activity, measuring seismicity and deformation, monitoring ash plumes by aircraft, and taking samples on foot.

Many volcano scientists have also turned to social media to answer questions from the general public about the recent eruption (like why is the eruption pink? Can you roast a marshmallow with lava?) and bust volcano myths floating online (expect no mega-tsunami from this eruption). The EGU’s own early career scientist representative for the Geochemistry, Mineralogy, Petrology & Volcanology Division, Evgenia Ilyinskaya, was invited to explain some volcano lingo on BBC News.

The volcano’s eruption has been ongoing for weeks, with no immediate end in site. Lava flows are still advancing across the region and volcanic gas emissions remain very high, says the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. You can stay up to date with the volcano’s latest activity on the agency’s site.

What you might have missed

A team of scientists from the PolarGAP project have found mountain ranges and three massive canyons underneath Antarctica’s ice using radar technology. These valleys play an important role in channeling ice flow from the centre of the continent towards the ocean, according to the researchers. “If Antarctica thins in a warming climate, as scientists suspect it will, then these channels could accelerate mass towards the ocean, further raising sea-levels,” reports an article from BBC News.

Also in Antarctic news, the Natural Environment Research Council (UK) and the National Science Foundation (US) have announced an ambitious plan to determine the Thwaites Glacier’s risk of collapse. The rapidly melting glacier sheds off 50 billion tons of ice a year, and if Thwaites were to completely go under, the meltwater would contribute more than 80 cm to sea level rise. “Because Thwaites drains the very center of the larger ice sheet system, if it loses enough volume, it could destabilize the rest of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet,” according to an article in Scientific American. The research team plans to collect various kinds of data on the glacier and use this information to predict the fate of Thwaites and West Antarctica. The $25-million (USD) joint effort will involve about 100 scientists on eight projects over the course of five years, posing to be one of the largest Antarctic research endeavors undertaken.

Meanwhile, looking out hundreds of millions of kilometres away, scientists have made an interesting discovery about one of Jupiter’s potentially habitable moons.

A team of scientists uncovered a new source of evidence that suggests Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons, may be venting plumes of water vapour above its icy exterior shell. The researchers came across this finding while re-examining data collected by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which performed a flyby 200 kilometres above the Europa in 1997. While running the decades old data through today’s more sophisticated computer systems, the research team found a brief, localised bend in the magnetic field, a phenomenon that is now recognised as evidence of water plume presence. These new results have made some scientists more confident that NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, set to launch by 2022, will find plumes on Jupiter’s moon.

Links we liked

- More than 6,000 maps from National Geographic’s 130-year-long history have been digitally compiled for the first time

- The mind-bending physics of Scandinavian sea-level change

- Making maps on a micrometer scale

- Earth’s magnetic field Is drifting westward, and nobody knows why

The EGU Story

A 2007 paper on global climate zones published in Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, a journal of the European Geosciences Union, has been named the most cited source on Wikipedia, referenced more than 2.8 million times. The Guardian and WIRED reported this story that neither Copernicus Publications nor the Australian authors of the paper were aware of.

EGU training schools offer early career scientists specialist training opportunities they do not normally have access to in their home institutions. Up until 15 August 2018, the Union now welcomes requests for EGU support of training schools in the Earth, planetary or space sciences scheduled for 2019.

In addition, the EGU will now accept proposals for conferences on solar system and planetary processes, as well as on biochemical processes in the Earth system, in line with two new EGU conference series named in honour of two female scientists. The Angioletta Corradini and Mary Anning conferences are to be held every two years with their first editions in 2019 or 2020. The deadline to submit proposals is also 15 August 2018.

And don’t forget! To stay abreast of all the EGU’s events and activities, from highlighting papers published in our open access journals to providing news relating to EGU’s scientific divisions and meetings, including the General Assembly, subscribe to receive our monthly newsletter.