Last year we prepared a round-up blog post of our favourite Imaggeo pictures, including header images from across our social media channels and Immageo on Mondays blog posts of 2014. This year, we want YOU to pick the best Imaggeo pictures of 2015, so we compiled an album on our Facebook page, which you can still see here, and asked you to cast your votes and pick your top images of 2015.

From the causes of colourful hydrovolcanism, to the stunning sedimentary layers of the Grand Canyon, through to the icy worlds of Svaalbard and southern Argentina, images from Imaggeo, the EGU’s open access geosciences image repository, have given us some stunning views of the geoscience of Planet Earth and beyond. In this post, we highlight the best images of 2015 as voted by our Facebook followers.

Of course, these are only a few of the very special images we highlighted in 2015, but take a look at our image repository, Imaggeo, for many other spectacular geo-themed pictures, including the winning images of the 2015 Photo Contest. The competition will be running again this year, so if you’ve got a flare for photography or have managed to capture a unique field work moment, consider uploading your images to Imaggeo and entering the 2016 Photo Contest.

Colourful hydrovolcanism. Credit: Stephanie Flude (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Different degrees of oxidation during hydrovolcanism, followed by varying erosion rates on Lanzarote produce brilliant colour contrasts in the partially eroded cinder cone at El Golfo. Algae in the lagoon add their own colour contrast, whilst volcanic bedding and different degrees of welding in the cliff create interesting patterns.

Grand Canyon . Credit: Credit: Paulina Cwik (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

The Grand Canyon is 446 km long, up to 29 km wide and attains a depth of over a mile 1,800 meters. Nearly two billion years of Earth’s geological history have been exposed as the Colorado River and its tributaries cut their channels through layer after layer of rock while the Colorado Plateau was uplifted. This image was submitted to imaggeo as part of the 2015 photo competition and theme of the EGU 2015 General Assembly, A Voyage Through Scales.

Water reflection in Svalbard. Credit: Fabien Darrouzet (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Svalbard is dominated by glaciers (60% of all the surface), which are important indicators of global warming and can reveal possible answers as to what the climate was like up to several hundred thousand years ago. The glaciers are studied and analysed by scientists in order to better observe and understand the consequences of the global warming on Earth.

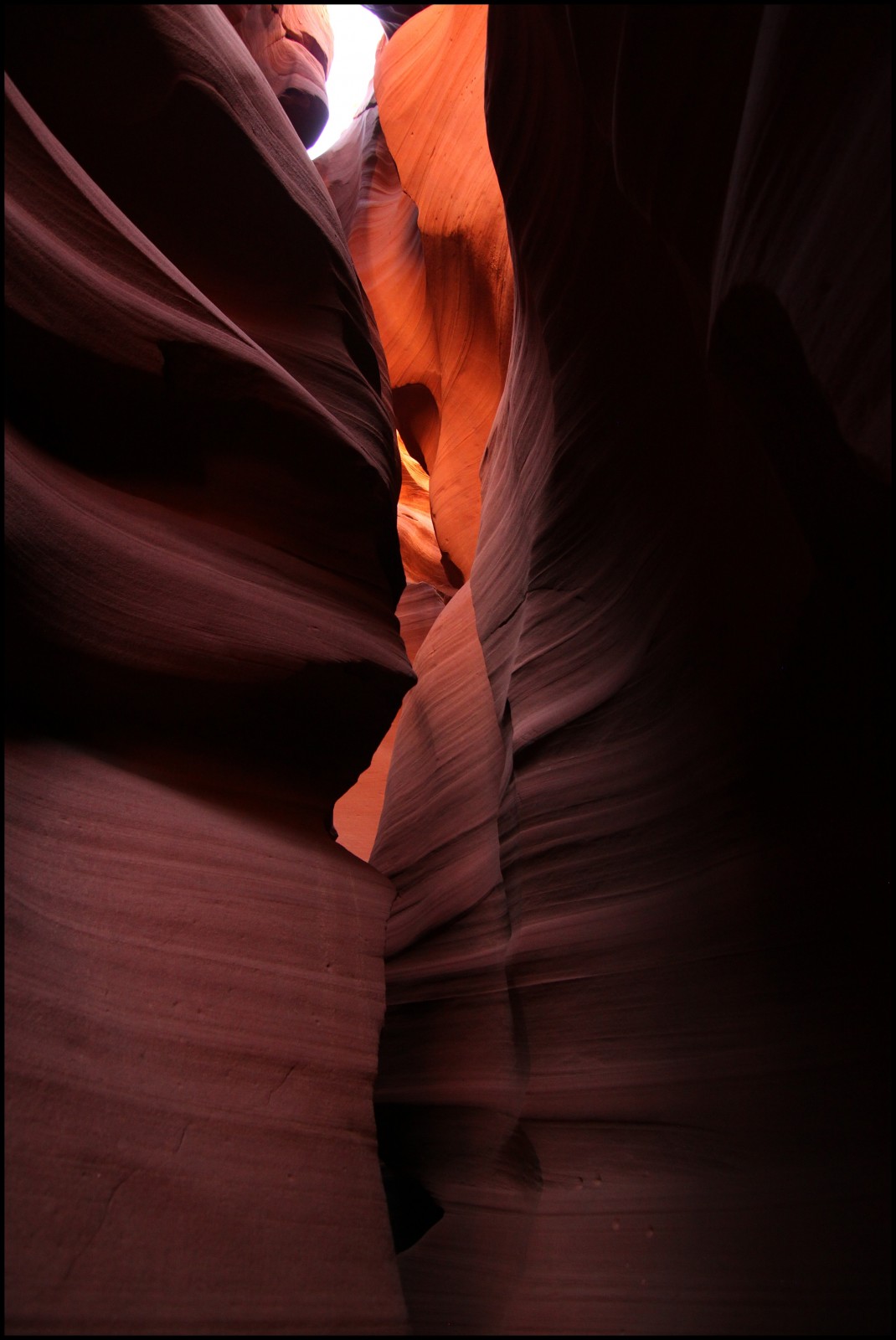

Waved rocks of Antelope slot canyon – Page, Arizona by Frederik Tack (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu).

Antelope slot canyon is located on Navajo land east of Page, Arizona. The Navajo name for Upper Antelope Canyon is Tsé bighánílíní, which means “the place where water runs through rocks.”

Antelope Canyon was formed by erosion of Navajo Sandstone, primarily due to flash flooding and secondarily due to other sub-aerial processes. Rainwater runs into the extensive basin above the slot canyon sections, picking up speed and sand as it rushes into the narrow passageways. Over time the passageways eroded away, making the corridors deeper and smoothing hard edges in such a way as to form characteristic ‘flowing’ shapes in the rock.

Just passing. Credit: Camille Clerc (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

An archeological site near Illulissat, Western Greenland On the back ground 10 000 years old frozen water floats aside precambrian gneisses.

Sarez lake, born from an earthquake. Credit: Alexander Osadchiev (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Beautiful Sarez lake was born in 1911 in Pamir Mountains. A landslide dam blocked the river valley after an earthquake and a blue-water lake appeared at more than 3000 m over sea level. However this beauty is dangerous: local seismicity can destroy the unstable dam and the following flood will be catastrophic for thousands Tajik, Afghan, and Uzbek people living near Mugrab, Panj and Amu Darya rivers below the lake.

Badlands national park, South Dakota, USA. Credit: Iain Willis (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Layer upon layer of sand, clay and silt, cemented together over time to form the sedimentary units of the Badlands National Park in South Dakota, USA. The sediments, delivered by rivers and streams that criss-crossed the landscape, accumulated over a period of millions of years, ranging from the late Cretaceous Period (67 to 75 million years ago) throughout to the Oligocene Epoch (26 to 34 million years ago). Interbedded greyish volcanic ash layers, sandstones deposited in ancient river channels, red fossil soils (palaeosols), and black muds deposited in shallow prehistoric seas are testament to an ever changing landscape.

Late Holocene Fever. Credit: Christian Massari (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Mountain glaciers are known for their high sensitivity to climate change. The ablation process depends directly on the energy balance at the surface where the processes of accumulation and ablation manifest the strict connection between glaciers and climate. In a recent interview in the Gaurdian, Bernard Francou, a famous French glaciologist, has explained that the glacier depletion in the Andes region has increased dramatically in the second half of the 20th century, especially after 1976 and in recent decades the glacier recession moved at a rate unprecedented for at least the last three centuries with a loss estimated between 35% and 50% of their area and volume. The picture shows a huge fall of an ice block of the Perito Moreno glacier, one of the most studied glaciers for its apparent insensitivity to the recent global warming.

Nærøyfjord: The world’s most narrow fjord . Credit: Sarah Connors (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Feast your eyes on this Scandinavia scenic shot by Sarah Connors, the EGU Policy Fellow. While visiting Norway, Sarah, took a trip along the world famous fjords and was able to snap the epic beauty of this glacier shaped landscape. To find out more about how she captured the shot and the forces of nature which formed this region, be sure to delve into this Imaggeo on Mondays post.

Helvetic Nappes of Switzerland. (Credit: Kurt Stüwe, via imaggeo.egu.eu)

The August 2015 header images was this stunning image by Kurt Stuewe, which shows the complex geology of the Helvetic Nappes of Switzerland. You can learn more about the tectonic history of The Alps by reading this blog post on the EGU Blogs.

(A)Rising Stone. Credit: Marcus Herrmann (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

The September 2015 header images completes your picks of the best images of 2015. (A)Rising Stone by Marcus Herrmann, pictures a chain of rocks that are part of the Schrammsteine—a long, rugged group of rocks in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains located in Saxon Switzerland, Germany.

If you pre-register for the 2016 General Assembly (Vienna, 17 – 22 April), you can take part in our annual photo competition! From 1 February up until 1 March, every participant pre-registered for the General Assembly can submit up three original photos and one moving image related to the Earth, planetary, and space sciences in competition for free registration to next year’s General Assembly! These can include fantastic field photos, a stunning shot of your favourite thin section, what you’ve captured out on holiday or under the electron microscope – if it’s geoscientific, it fits the bill. Find out more about how to take part at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/photo-contest/information/.

Pingback: Where Geology meets Art: EGU’s ImagGeo | thenoblegasbag