Migration is commonly perceived as a strategic response to address the repercussions of environmental threats and climate change. The International Organization for Migration defines ‘environmental migrants’ as those individuals who alter their place of residence due to a sudden or progressive change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions. Conversely, those who either choose not to migrate or are unable to do so have been described in various ways, including as immobile, nonmigrants, sedentary, stuck, left behind, or trapped population [1].

A sedentary bias has long shaped our perspective, framing migration as a problematic phenomenon, a notion evident in early reports on the migratory impacts of climate change on population [2]. The prevailing assumption was that immobility in response to climatic and environmental changes required no investigation, whereas migration was a sign of crisis. The early narratives on the impacts of climate change on migration and displacement predominantly overlooked the prospect that we may be entering a world where fewer people can move due to climate change. That immobility, too, presents its own set of challenges [1]. Certain literature delves into the causes of immobility and the primary obstacles to environmental migrations, interpreting them through an economic lens. People find themselves geographically “trapped” due to factors such as asset loss, entrapment in poverty cycles, or a lack of financial capital to migrate [3].

In Zambia, a connection was found between unfavorable climate conditions and increasing migration, specifically in wealthy migrant-sending districts [4]. Further, it is emphasized that populations “too poor to migrate,” are facing immobility and are exceptionally vulnerable. This stems from “deep and persistent” poverty, the financial expenses associated with migration, and the further deterioration of already fragile economic livelihoods under the influence of climate change [4].

Is climate migration a security issue?

In scientific literature and policy reports, the narrative often solidifies climate migration as an imminent security crisis. This emphasis on securitization—framing climate change and migration as a security risk—is actively sustained by public funding schemes supporting scientific research. Consequently, the outcome of scientific research guides national, regional, or international policy development. To mitigate potential harm to the destination areas of environmental migrants, the funding policies aim to sustain the population in their original places of origin [3].

In Iran, the substantial migration from rural regions to urban areas resulted in the establishment of informal settlements around cities. One of the main reasons behind these migrations is water scarcity and anthropogenic drought. This has compelled decision-makers to strategize in a manner aimed at retaining the rural population in their original locations, despite inadequate resources for sustaining agricultural activities and population livelihood. Moreover, this population is also vulnerable to additional environmental hazards, including sinkholes arising from the excessive depletion of underground water resources [5].

On the other side, recently, the conceptual alignment of migration as adaptation is inherently associated with advocating solutions that enable migration out of vulnerable areas. However, this approach may inadvertently introduce a bias favoring mobility in policy considerations, potentially overlooking the right of individuals to stay in their own places [1].

“Should I stay, or should I go?” Choosing to remain is a viable option

Recent empirical evidence suggests that all the individuals choosing to remain despite climate risks are not a trapped population; rather, many make voluntary decisions based on various reasons to stay in their own places [6]. In the highland regions of Peru, the prioritization of place attachment over resource limitations has been acknowledged as a factor explaining why some individuals choose to stay. Similarly, in Indonesian regions prone to coastal flooding, the prevailing preference among most individuals is to stay and adapt in situ, primarily influenced by social factors such as community relationships [1]. As another example in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh, despite facing recurring extreme climatic events, including tropical cyclones and storm surge-triggered flooding, the local population has opted to remain in their current locations. Over the past four decades, this region has experienced significant economic and non-economic damage due to these climatic challenges, rendering it relatively poorer compared to other areas. The inhabitants, accustomed to these hazards, perceive them as common occurrences. After climatic shocks, particularly cyclones, the residents receive support from their communities through social networks [7].

The decision to stay is influenced by factors such as financial and non-financial assistance, anticipated better income prospects, affordable living costs, strong social capital, and the skills to adapt to local conditions. Despite lacking a regular monthly income, voluntary non-migrants manage their basic needs through support from relatives, political leaders, social elites, government, and non-governmental organizations [7]. The key question that emerges is the long-term sustainability and economic viability of this situation when compared to migration.

Infrastructural facilities play a crucial role in influencing decisions related to environmental migration. For instance, in a study conducted in Bangladesh, families residing in high-quality houses designed to withstand cyclones and situated near emergency infrastructure and institutional support—such as easy access to cyclone shelters in the community—express a preference to stay in place despite environmental risks [6].

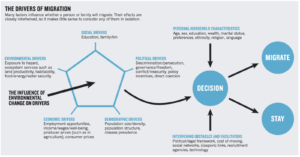

The drivers of migration and the factors that shape decisions regarding whether to stay or migrate from a location [8].

Need for more holistic studies on migration

Environmental migration is a complex process influenced by a range of factors, including characteristics of the environmental hazards (e.g., slow- or fast-onset), their recovery time, and many community-level aspects such as culture, migration history, development levels, etc. [9, 10]. However, statistically significant predictors like economic status and occupation primarily determine the population’s capacity to migrate. In this context, it would be essential to develop more comprehensive studies able to assess the suitability of migration destinations based on the population’s abilities and migration capability, as well as studies comparing migration and staying in place as adaptation options from a holistic perspective. Such studies could contribute significantly to understanding both migration and staying in place as valid forms of adaptation.

References

[1] C. Zickgraf, “Theorizing (im)mobility in the face of environmental change,” Reg Environ Change, vol. 21, no. 4, p. 126, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10113-021-01839-2.

[2] N. Myers, “Environmental Refugees in a Globally Warmed World: Estimating the scope of what could well become a prominent international phenomenon,” BioScience, vol. 43, no. 11, pp. 752–761, Dec. 1993, doi: 10.2307/1312319.

[3] I. Boas et al., “Climate migration myths,” Nat. Clim. Chang., vol. 9, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0633-3.

[4] R. J. Nawrotzki and J. DeWaard, “Putting trapped populations into place: climate change and inter-district migration flows in Zambia,” Reg Environ Change, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 533–546, Feb. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1224-3.

[5] S. Mohammadi and M. Khanian, “Staying in Crisis: Choice or Coercion a Review of the Reasons of Rural-to-Urban Migrations Due to Environmental Changes in Iranian Villages,” Space and Culture, p. 12063312211018396, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1177/12063312211018396.

[6] B. Mallick, “Environmental non-migration: Analysis of drivers, factors, and their significance,” World Development Perspectives, vol. 29, p. 100475, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2022.100475.

[7] F. Khatun et al., “Environmental non-migration as adaptation in hazard-prone areas: Evidence from coastal Bangladesh,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 77, p. 102610, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102610.

[8] R. Black, S. R. G. Bennett, S. M. Thomas, and J. R. Beddington, “Migration as adaptation,” Nature, vol. 478, no. 7370, Art. no. 7370, Oct. 2011, doi: 10.1038/478477a.

[9] S. N. A. Codjoe, F. H. Nyamedor, J. Sward, and D. B. Dovie, “Environmental hazard and migration intentions in a coastal area in Ghana: a case of sea flooding,” Popul Environ, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 128–146, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1007/s11111-017-0284-0.

[10] B. Mallick, C. Priovashini, and J. Schanze, “‘I can migrate, but why should I?’—voluntary non-migration despite creeping environmental risks,” Humanit Soc Sci Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-01516-1.

Post edited by Silvia De Angeli and Shreya Agora