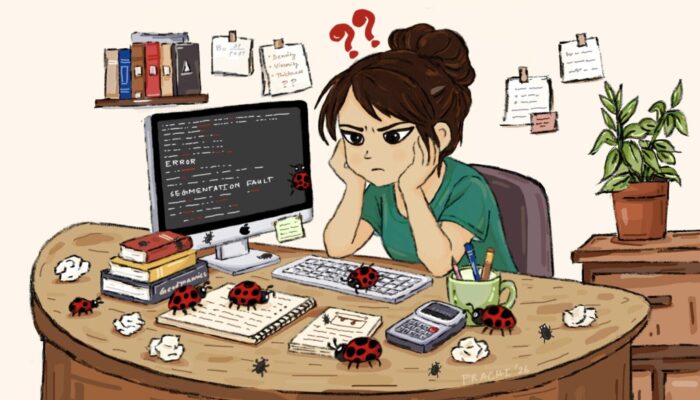

An illustration by Prachi Kar

Mantle convection may unfold the hidden stories of planetary interiors over billions of years, but geodynamic models can crash in milliseconds. While figures in papers often show smooth convective flows with elegant plumes and slabs, the path to those results is not very easy. This week, Prachi Kar, a PhD candidate at Arizona State University, shares her honest thoughts on the part of geodynamics no one advertises: the art and emotional labor of debugging.

Prachi Kar, School of Earth and Space Exploration, ASU

“Okay. Finally. The code is done. This is it. Time to run the model.”

-

- Run

- Error

“Oh wow. Not working. Ughhh…. Cool, cool, cool. Bugs again. Alright, no problem. Let’s be systematic. I’ll print some values.”

- Add print statements

- Run

- Error

“Ughhh… again an error! Why? Why is it still not working? There must be another bug. Obviously.”

- A few minutes later…

“How did I not see this? Stupid me. This is very BASIC. I call myself a scientist!!!”

“Oh. Ohhh. Wait. That’s why it wasn’t running. Makes sense. Alright. Let’s go over again. Now, it should work.”

- Run (after 7.56441 seconds …)

- Segmentation fault

“Noooooo. Where did YOU (the latest error) come from? Will I spend my entire academic life debugging code? Is this what mantle convection really is? Just… digital suffering?”

“One bug. Fixed. Two bugs. Fixed. No, definitely more bugs. Infinite bugs. Maybe the real convection is the instability inside me all along.”

I would bet it is like this, the life of most geodynamicists.

When I first encountered the subject Geodynamics, I was fascinated by the science – mantle flow, convection cells, plate tectonics, the grand choreography of Earth’s interior. To be honest, I fell in love with it. I decided to pursue a PhD in geodynamics, imagining that I would spend my days running elegant models that would quietly reveal how the Earth works. Reality, however, had other plans.

Nobody told me that most of my time would be spent staring at code, wondering why the temperature had suddenly become negative or why a model that ran perfectly yesterday now refuses to run for more than 3 timesteps. It turns out that geodynamics is not just about understanding the dynamic behavior of the Earth; it’s also about understanding why my model of Earth or Moon, or any other planetary body, is angry with me today (and probably every day).

If you haven’t experienced the instant explosion of a model accompanied by unreadable error messages, the slow betrayal of a run that gives you hope for hours before ending in a segmentation fault, the beautiful lie of results that look stunning but make absolutely no physical sense, or the mysterious ghost bug that disappears the moment you try to show it to someone else – are you even a geodynamicist? If this sounds familiar, cheers. Welcome to the club!

On paper, geodynamic modeling looks quite straightforward: define your equations, select your parameters, apply boundary conditions, and let the mantle convect. In practice, it looks more like this:

Set up a model → Watch it crash → Change something small → Make sure to change it everywhere else → Watch it crash differently → Yell at the screen → Take a break → Repeat.

At first, this feels like a failure. I started to wonder whether I am bad at coding or just so dumb that I get stuck at each step, while everyone has figured this out long ago. But over time, I have realized something important: Debugging is not the obstacle to your success; it is the path to your success. And it is not just about fixing technical errors; it is emotional labor. There is frustration when nothing works, embarrassment when you ask what feels like a basic question, and a special kind of despair when others seem to run perfect models effortlessly while yours refuses to cooperate.

But is debugging only frustrating? Or does it have a brighter side?

I would argue that debugging is one of the most effective ways to truly learn the physics and mathematics behind your model. When something breaks, you are forced to ask deeper questions: How can this be interpreted in the physical world? Which assumptions did I just violate? Is everything truly being conserved? Some of the hardest lessons come from realizing that a failing model is not a judgment on your intelligence. Very often, the bugs are almost embarrassingly simple – a misplaced sign, an index off by one, a parameter defined in the wrong units. The real Earth is complex; our mistakes are usually not.

Gradually, you develop intuition, not the kind you gain from textbooks, but the one that comes from watching your models misbehave and figuring out why. Debugging makes you more observant, more careful, more honest about uncertainty. In that sense, every bug is an unplanned learning opportunity.

And then, at some point, something changes quietly. Your model crashes, but instead of panic, you know which things to check first. You fix things one by one. You trust your intuition more than the code output. That’s when you realize that debugging hasn’t been slowing you down. It’s been training you. Running a model makes you a user. Debugging makes you a geodynamicist.

So if you are currently trapped in a loop, chasing an irritating bug and slowly convincing yourself that you will never be a “real” geodynamicist – Pause. You are not alone, and you are not a failure. You are learning the language of a system that is layered, nonlinear, sensitive, complicated, and beautiful – much like the Earth (or any other planetary body) itself. Debugging will improve your coding skills, even if you never considered yourself a “computer person.” Be patient. Don’t expect a magic fix. Change one thing at a time. Print intermediate values and ask whether they make physical sense. Read the code like a story instead of trying to understand everything at once. Talk to your colleagues. Know your problem, and ask for help. Don’t look for cheat codes; use AI responsibly as a tool, not a crutch.

Remember, behind every smooth mantle flow, there is a long history of crashes. And that’s not a weakness of our field – it’s a part of the journey.