During the working day, Matthew Kemp is a seismology PhD student at the University of Oxford. In his spare time, however, he writes and performs musicals about science as part of the duo Geologise Theatre, using stories to explain complex scientific concepts to a variety of audiences – from dinosaur extinction to climate change. In this week’s post, he discusses how classical story-telling structures can be applied to science communication and scientific paper writing.

The scientific process is the most fundamental story of humanity – researchers look at the world as it is, see questions that need answering and go on a voyage of discovery.

I love stories. They are an essential part of human existence, vehicles to understand how the world around us works, both physically and emotionally. Stories put random facts and events into a cohesive and logical structure, making them easier to understand and remember. On the other hand, science itself is full of facts and processes, and scientific discovery is full of amazing narratives. This got me thinking… could classical story structure be used to communicate science and help when writing scientific papers?

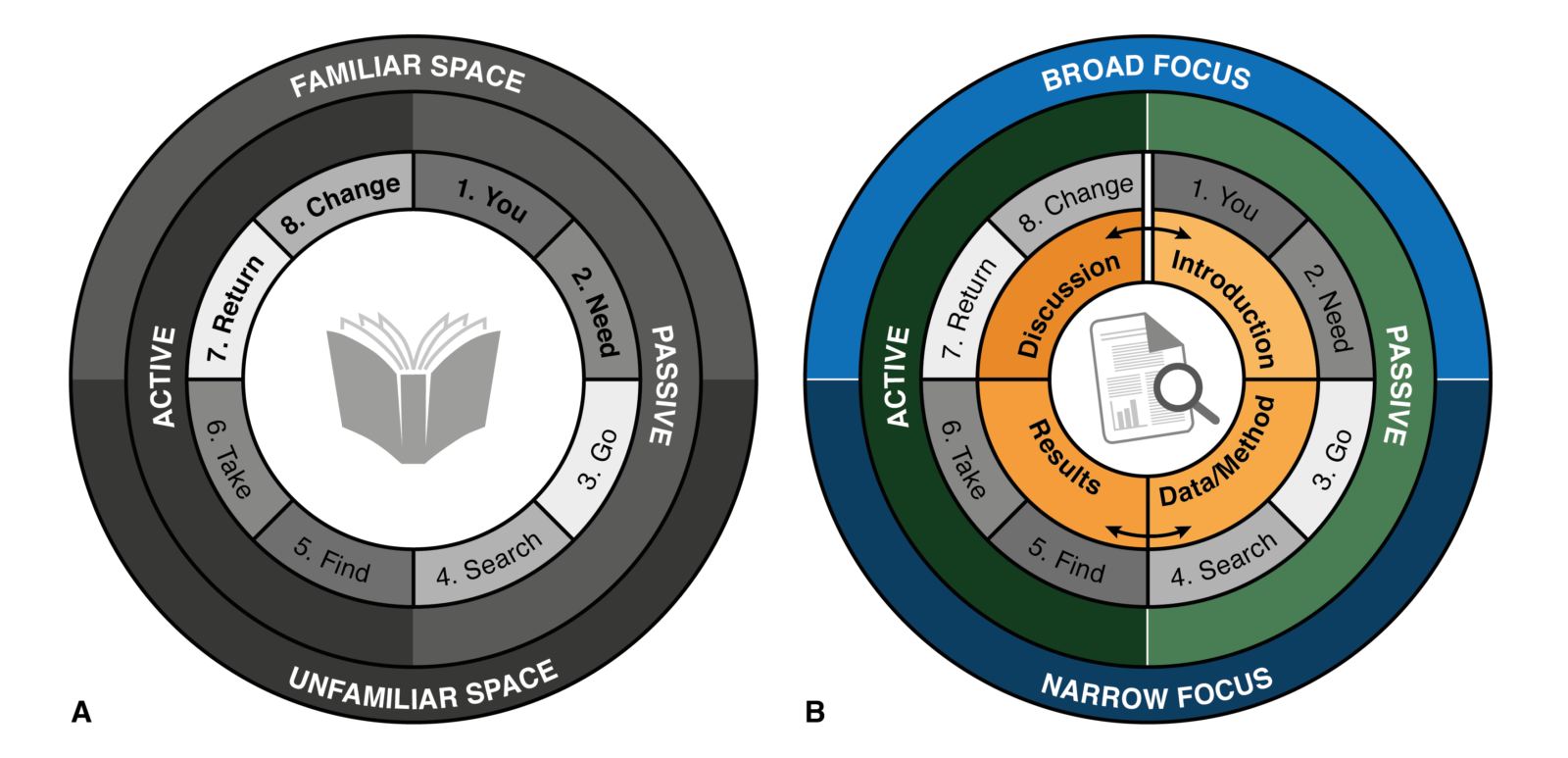

On my voyage into the narrative discourse I came across a story structure used by Dan Harmon, creator and writer of hit comedies Community and Rick and Morty. Harmon’s Story Circle, (Fig. 1A) is based upon Joseph Campbell’s classical “Hero’s Journey”, and imagines the story as a circle split into eight segments. Each segment represents a crucial part of the story, as follows: YOU (1) introduce the hero in a familiar setting, but they NEED (2) something, so they GO (3) into an unfamiliar situation, they SEARCH (4) for it by undergoing trials, they eventually FIND (5) what they wanted, TAKE (6) it with difficulty, RETURN (7) to the familiar situation, and are CHANGED (8) because of that journey.

In the right hemisphere of the story circle (Fig. 1A) the hero is more passive whilst in the left hemisphere they are more active. Similarly, whilst in the upper hemisphere, the hero is within familiar settings, whereas within the lower hemisphere they are venturing into the unknown.

Fig 1: Diagram illustrating the concept of the story circle (A) and how it can be applied for scientific paper writing (B)

You might be wondering what does this all have to do with science communication or scientific paper writing? As it turns out, the main sections that scientific papers are often split into conform extremely well to Harmon’s Story Circle (with the exception of the abstract and the conclusions, as those are essentially mini story-circles bookending the paper). And there is also the fact that, regardless of the journey, the hero is always changed in some way…and change is a key part of scientific research. Not convinced? Let me walk you through it (Fig. 1B).

In the Introduction, YOU (1) set the scene, introducing the scientific ideas on a broad scale, explaining the work that has already been done in this area of research. However, this work is incomplete, and there is a question that you NEED (2) to answer, so the paper then crosses the threshold into a specific and focussed research area (3. GO). The Methods section describes the variety of skills and processes needed to answer the question (4. SEARCH), before detailing the FINDings (5) of these trials in the Results and giving hints at how the question can be answered (6. TAKE). Finally, in the Discussion, the paper RETURNS (7) from the specific research area to the wider context of the study. In doing so, it shows how current understanding has CHANGEd (8) as a result of the journey taken whilst carrying out the research presented in the paper.

As before, the hemispheres of the circle (Fig. 1B) are also meaningful. Some paper sections tend to focus on recounting work that has already been done, or describing how research is conducted (right hemisphere, “passive”), whilst others present new findings, and discuss how those contribute to or enhance current scientific understanding (left hemisphere, “active”). A paper’s introduction and discussion sections (top hemisphere) are normally written with a broader view, whereas methods and results (bottom hemisphere) generally narrow the focus down to answering specific questions.

One final, and perhaps most practically useful feature of this “story circle” approach to paper writing, are the arrows in the inner circle of figure 1B. In fictional stories, if you set up something in the beginning of the story, you should have a payoff for it at the end. Equally, you shouldn’t randomly bring something new to the story in the final act if it’s not already been set up in the first act. This works for scientific paper writing too: you shouldn’t ramble in the introduction about something that you have no intention of discussing later on, neither should you draw conclusions you haven’t supported with background information (or present results obtained by methods you haven’t explained, you get the idea).

Perhaps, like the hero of the story, by reading this blog post and delving into the unfamiliar world of narrative structure, you have been changed and will return to academic life with a new tool in your paper-writing arsenal. Perhaps not. Overall I hope this shows that the scientific process is the most fundamental story of humanity – researchers look at the world as it is, see questions that need answering and go on a voyage of discovery to find the answers. When they return, the world has changed because of what was found on that journey. And so the cycle repeats, the circle keeps turning, and the ideas keep changing after every iteration. In science, however, we will never truly write “The End”.

Further Reading: Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (New World Library, 1949) Dan Harmon, Story Structure 101 (Channel 101 Wiki, 2009) John Yorke, Into the Woods (Penguin Random House, 2013) K.M. Weiland: 5 Secrets of Story Structure and Creating Character Arcs (PenForASword Publishing, 2016)