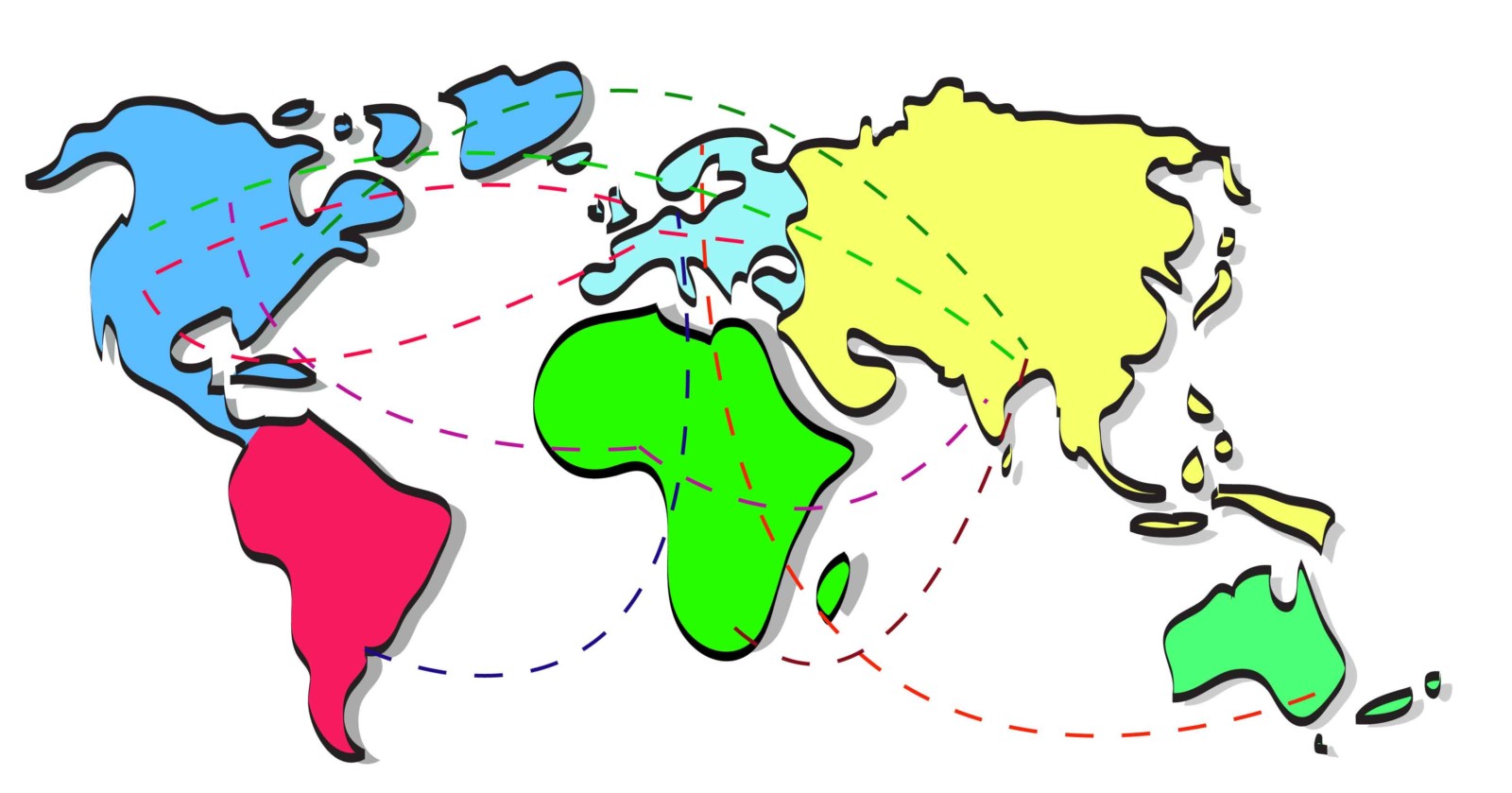

After spending about three decades in the hustle-bustle of Asian megacities, I landed up in a quiet European town to continue my research work as a postdoc. When you know you will not meet your family soon in person, you know that you will not get the food you love and, the climate that has guided you in the sun and shadow will be very different; you may expect a life struggle. Yet, people have digested the new environment and found a new life in a completely different place. Often, they get used to the new “home” so much that they have settled down in a distant part of the world. In this week’s wit and wisdom, I have compiled stories from seven geoscience researchers across the globe about their continental drifts in pursuit of research work.

Shailee Bhattacharya, From India to the US

Shailee completed her graduation in Kolkata, India, and then moved to West Virginia, the US, as a PhD student. She is an avid writer, singer and currently working on Shale energy. When I asked her about her new life in the US, she shared her thoughts on various aspects, including mental health issues.

“Looking back at myself in 2018, I see this naïve 24-year-old aspiring to earn a Ph.D. degree in Geosciences from one of the most sought-after Biogeochemistry labs in the United States. Little did she know that pursuing a degree in higher education in a foreign country was just the tip of the iceberg of challenges that she was throwing herself into. Two and a half years later, I can now vouch that I am better at surviving, as opposed to merely ‘living’ a sheltered life in India. While studying abroad has its perks, all that glitters is not gold. The battle to find your identity in a multiracial and multicultural environment is the first of the many roadblocks one may encounter. The way out of the problem, however, is through it- constant dialogue with oneself regarding one’s value systems, why they are what they are.

“Looking back at myself in 2018, I see this naïve 24-year-old aspiring to earn a Ph.D. degree in Geosciences from one of the most sought-after Biogeochemistry labs in the United States. Little did she know that pursuing a degree in higher education in a foreign country was just the tip of the iceberg of challenges that she was throwing herself into. Two and a half years later, I can now vouch that I am better at surviving, as opposed to merely ‘living’ a sheltered life in India. While studying abroad has its perks, all that glitters is not gold. The battle to find your identity in a multiracial and multicultural environment is the first of the many roadblocks one may encounter. The way out of the problem, however, is through it- constant dialogue with oneself regarding one’s value systems, why they are what they are.

Secondly, the resources for addressing mental health issues, although plenty, can be expensive. Therefore, figuring out a healthy and sustainable lifestyle early on, that enables growth in both personal and professional spheres, is of paramount importance. That means having a healthy balance of eat, sleep, work and play. Living abroad can rob you of your entitlements and privileges, but it was an opportunity for immense growth for me. Besides the constant threat of losing parts of your true self while fighting to survive, there may be other less intense, but pertinent problems. Language, weather and acclimatisation. Even as an Indian, who is well accustomed to conversing in English, I took some time to pick up the nuances of American English and garner the ability to predict how I was expected to respond in any personal or professional situations. I learned all over again that communication is 70% comprehension and 30% articulation. While I was learning the ways and manners, small mistakes seemed like life-changing moments, but it felt that the western world is a little more forgiving and allows us to make mistakes and grow. I have tried to keep my head down with gritted teeth, use my wisdom and knowledge to deliver quality work, and focus on my development as an individual when the world was and is still reeling under the blow of the pandemic. The path to a higher degree requires self-preservation and determination but may seem like a bigger challenge in the prolonged absence of friends and family, but you soon might realise the incredible force of nature you are when such a difficulty does set in.”

Benjamin Fosu, From Ghana to India to Canada

Benjamin came to Bangalore, India, after completing his graduation from Accra, Ghana. Recently, he has moved to Quebec, Canada, as a postdoc. A jolly, friendly isotope geochemist, who has actively participated in different programs in India, including translating and singing a Bengali song in his mother tongue Asante Twi, tells that several things were changed during his sojourn in India.

“Moving abroad for studies or work can be quite exciting and eye opening but it certainly comes with a price. After my graduation from the University of Ghana, I was torn between taking up a job at home and pursuing further studies abroad, I just wasn’t sure about what I really needed at that time. After several days of pondering on what to do, I eventually made a tough but worthy decision to study abroad, and my destination was India. I was confident I had a fair idea of what my expectations in India would be, but reality struck me hard when I finally arrived in the city of Bangalore. There was much more to what I had seen through mainstream media and the Indian movies that I enjoyed watching on Sundays. On the brighter side, the beauty of India and her people was a remarkable sight – the vast landscapes, the evergreen cities and most importantly the amazing weather that Bangalore had to offer. The food was wonderful with countless varieties to choose from, but that was the first of my initial struggles. The cost of living was very affordable; transportation wise, food, mobile and Internet connectivity all came very cheap. This afforded me some level of financial comfort and accessibility to many captivating activities.

“Moving abroad for studies or work can be quite exciting and eye opening but it certainly comes with a price. After my graduation from the University of Ghana, I was torn between taking up a job at home and pursuing further studies abroad, I just wasn’t sure about what I really needed at that time. After several days of pondering on what to do, I eventually made a tough but worthy decision to study abroad, and my destination was India. I was confident I had a fair idea of what my expectations in India would be, but reality struck me hard when I finally arrived in the city of Bangalore. There was much more to what I had seen through mainstream media and the Indian movies that I enjoyed watching on Sundays. On the brighter side, the beauty of India and her people was a remarkable sight – the vast landscapes, the evergreen cities and most importantly the amazing weather that Bangalore had to offer. The food was wonderful with countless varieties to choose from, but that was the first of my initial struggles. The cost of living was very affordable; transportation wise, food, mobile and Internet connectivity all came very cheap. This afforded me some level of financial comfort and accessibility to many captivating activities.

Bangalore city was vibrant with African and many other international students, which made it more liveable considering my needs for feeling at home irrespective of my geographic location. As an evening person, the bustling nightlife in Bangalore made my adaptation to life there easier. Maintaining a decent balance between academic and social life in a new environment was a daunting task to begin with. However, the friends that I made (both Indians and expats), the communities and student groups that I was involved were very critical to my survival. Aside language barriers, the sharp contrast in cultural backgrounds and differences in lifestyle were the major impediments to social inclusion in the city, and the severity increased as one moved outside the academic and work environments. This was at some point paralleled with difficulty in connecting with people outside of my professional circle. I was compelled to be cautious when approaching people (strangers in particular) and also be selective about my language. This partly affected my confidence in public appearances during my initial days but I somehow managed to move past this gloominess eventually.

Before coming to India, I was pretty much intolerant and dismissive of ideas that do not conform to my beliefs. I probably took offence in minor things, aside from being impatient about almost everything. However, my exposure and engagement with dozens of people of different nationalities gave me a completely new perspective about human behaviour and values. Also the extracurricular activities that I was involved in – having spent a considerable amount of my time organising social and cultural events with fellow friends made me more accommodating and understanding. I probably identified as an introvert while back in Ghana but I became more outgoing and warmed up easily to people as the years passed in India. Thanks to India, it is safe to say I now have a social life and perhaps identify as an ambivert.”

Lucas Calvo, From Argentina to Germany

A few days back, I met Lucas, who is a Masters’ student at the University of Bayreuth. I was quite excited to know that he is from La Plata, Argentina. Being a big fan of Argentine football art, I could connect to him quickly. When I asked him how was his long journey, he told,

“Taking a plane and travelling more than 11,500 km to come to Germany was (is, and it will ever be) a life-changing experience for me. This was a big step since I was leaving my comfortable, well-known environment in every aspect of my life.

“Taking a plane and travelling more than 11,500 km to come to Germany was (is, and it will ever be) a life-changing experience for me. This was a big step since I was leaving my comfortable, well-known environment in every aspect of my life.

In academic terms, geology has quite a different approach in La Plata (the city where I was born and raised) than in the Bayerisches Geoinstitut, where I am studying my master’s. Here, based on laboratory work, we learn to simulate conditions of the deep Earth: “30 GPa? That’s low pressure”, as a BGI professor said once. On the other hand, in Argentina, we are more committed to field work, hence I had to leave my pickaxe resting at home. Both of them are very exciting, and if I had never come here I would not have discovered this very interesting face of geology.

Oh, and about starting a new life in another country (in corona-times), at least for me, was much more positive than expected. People are very kind, and landing in a culture where beer is in the frontline is always an advantage: As soon as I got to know people, beer was almost an everyday occurrence. That is why I would replace the “having Mate people understand each other” of my culture by “having a beer people understand each other”.

In cultural aspects, Germany is definitely different to Argentina, but such is any country. Although due to the language I would be feeling closer to home by living in Spain, this place has proved that it has quite some offers to make you feel like home, and people here are open and kind. Fortunately for us, the Ausländers, when people do not speak English they do their best, and if you speak a bit of German you would understand each other. Such was my experience in capoeira, this Afro-Brazilian martial art where we pretend to dance while throwing kicks to each other. I used to do it in my hometown and when I discovered a Capoeira school in a city nearby I did not doubt starting there. In this place where no international people are around I found people with open arms, with whom I am improving my Tarzan-ish German.

Of course, there were moments where I felt lonely. Fortunately, I could rely not only on the people I got to know here but also my best friends from childhood who by chance came to live in cities less than 3 hours away from here. However, by being abroad and alone you learn a lot about yourself and how to face good and not-so-good situations, and definitely you learn to be independent and emotionally stronger. More than a year ahead since my arrival, I can strongly advise anyone who has this idea rooted in their mind.”

Grace Shephard, From Australia to Norway

Among all the people I know, I think Grace has travelled the longest distance, from her home in Australia to Norway! But the idea of “distance” and “home” has got a new meaning in her journey.

“When someone finds out that I am an Australian living in Norway the following three questions are almost guaranteed. It usually begins with; “How do you deal with the cold”? I launch into my usual repertoire about proper building insulation, woolen layers, and comfort in the knowledge that there are fewer spiders in Scandinavia.

“When someone finds out that I am an Australian living in Norway the following three questions are almost guaranteed. It usually begins with; “How do you deal with the cold”? I launch into my usual repertoire about proper building insulation, woolen layers, and comfort in the knowledge that there are fewer spiders in Scandinavia.

After an inevitable deviation about arachnids, and unsolicited marsupial fun-facts*, it is followed by: “So, why did you move (so far away) to Norway?” More often than not, I elaborate on the distance aspect of the question. “I study the Arctic, so it made a little more sense to move closer to it.” Whilst only part of the reason why, this was indeed a big factor; the final chapter of my PhD thesis was on the evolution of the Arctic, and from that moment I was hooked. That year (2013) a brand new institute that had just opened at the University of Oslo, and it, and Norway, seemed like a great fit personally and professionally. I think that having supporting colleagues is an crucial part of a successful transition, and building connections in broader society is an additional, albeit more challenging, important step.

Home is where heart is…

But it is the third question I have increasingly come to dread – “Don’t you miss home?” The inherent dilemma of where home is (whether based on residency and/or location of loved ones) will be familiar to many expat readers. Whilst innocently asked, and after eight years and counting, it is one that I can no longer brush off lightly. Compounded by the pandemic, border restrictions, fixed-term contracts, as well as a recent bereavement (… and also new aunty duties amongst family and friends!) missing home has certainly become my own personal elephant in the room. Science is challenging, inspiring, and rewarding but it isn’t everything. Please do keep a special eye out for your colleagues who are any distance from their home, however far that may be.

* To end on the aforementioned marsupial fun-fact – did you know that wombats poop in cubes? ”

Tuhin Chakraborty, From India to South Africa

“When I got the postdoctoral position in South Africa, I was intrigued by the idea of traveling to a new country. I had heard so much about the natural beauty of South Africa and the prospect of exploring new places made me jubilant. However, COVID delayed the visa process by 5 months and I finally landed at Johannesburg airport on a cold June afternoon. The fact that the majority of the population here speaks English came as a major relief. The journey from my homeland to Rhodes University, Grahamstown was a long and tiring one. Sceneries outside began to change as I moved from Johannesburg, gauteng to Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape and finally reached Grahamstown

The city is fairly small, a university town. Although I was mentally prepared for the southern winter, the sharp drop in temperature from hot Kolkata summer to cold winter was quite shocking. The local crowd here is extremely welcoming and friendly. In case you are someone who forgets things at the supermarket counter, rest assured that there will always be someone calling and running after you.

The campus was deserted as the city was under lockdown and it was difficult to find people to talk to. However, slowly people started returning to the campus and I started making new friends. I joined the University Chess Club and gradually got to know some cool people there. I also started to work on my postdoctoral project. Rhodes University boasts strong technical and educational support for its researchers but the crown jewel is its Central Library and being a bookworm, this is the place that interests me the most.

What I miss the most here are the short tea breaks we used to take back at IIT Kharagpur. Given the prices of Tea and coffee here at University Café, possibly it is for the best. Although weekend parties are pretty common here and weekend feeling starts creeping in from mid-Friday. COVID restrictions had halted normal life but with time as the rules are getting relaxed, the city is gradually coming back to life. The lack of public transport is something I find disconcerting in this place. It’s one of the reasons I could not travel as I would have wished to. Luckily a friend of mine owns a car!

It is almost six months I have been in South Africa and I find this country to be extremely diverse, full of life, loving and welcoming with good, caring people. I hope to make great new memories in the coming years.”

Avigyan Chatterjee, From India to the US

All experiences are not as smooth as Tuhin’s. Avigyan, a PhD student in seismology at the University of Texas, Austin, shared his thought about it.

“Hailing from an urban, middle-class, liberally educated Bengali family, it was almost drilled into me from a vastly nascent age, that moving abroad for higher education, would bring forth better fortune, and fortune was always invariably measured in units of intellectuality, which in turn, helps preserve the ideology and interests of the Bengali Intelligentsia. Leaving behind the known comforts of home is hard. What’s even harder is adjusting to life that is unfamiliar, cold and lifestyles so visibly aberrant to your own. Oregon, the stepchild of the West Coast of the US, with its bucolic and unhurried setting endeared me to it, but there are things that neither the Indian education system nor the society in general prepares you for. I never quite understood the power of community because I was fortunately never faced with this issue back in my own country, but once in a foreign land, this seemingly effortless matter, felt like a task. How hard is it to make friends after all? Within a few months of moving, the pandemic waltzed in and the little bonds of companionships that were forged were suddenly strained and, in some cases, completely obliterated. Graduate school can be very isolating because much of the work is being done independently. Social events on campuses also tend to be centered on undergraduate students, so many graduate and professional students may not feel connected to their institutions either. As I transitioned from the undergraduate level to the graduate and professional level, I often struggled to accept my own success and questioned by sense of belonging. The very pronounced lack of diversity in geosciences is also a very worrying statistic. Being the only international student in the department meant, I often felt out of place and isolated.”

“Hailing from an urban, middle-class, liberally educated Bengali family, it was almost drilled into me from a vastly nascent age, that moving abroad for higher education, would bring forth better fortune, and fortune was always invariably measured in units of intellectuality, which in turn, helps preserve the ideology and interests of the Bengali Intelligentsia. Leaving behind the known comforts of home is hard. What’s even harder is adjusting to life that is unfamiliar, cold and lifestyles so visibly aberrant to your own. Oregon, the stepchild of the West Coast of the US, with its bucolic and unhurried setting endeared me to it, but there are things that neither the Indian education system nor the society in general prepares you for. I never quite understood the power of community because I was fortunately never faced with this issue back in my own country, but once in a foreign land, this seemingly effortless matter, felt like a task. How hard is it to make friends after all? Within a few months of moving, the pandemic waltzed in and the little bonds of companionships that were forged were suddenly strained and, in some cases, completely obliterated. Graduate school can be very isolating because much of the work is being done independently. Social events on campuses also tend to be centered on undergraduate students, so many graduate and professional students may not feel connected to their institutions either. As I transitioned from the undergraduate level to the graduate and professional level, I often struggled to accept my own success and questioned by sense of belonging. The very pronounced lack of diversity in geosciences is also a very worrying statistic. Being the only international student in the department meant, I often felt out of place and isolated.”

Adina Pusok, From Romania to the UK to Germany to the US to the UK

“I am what you would call an academic nomad. Currently, I am a postdoctoral researcher in Geodynamics at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, but until now, I have made 4 international and institutional moves since I started my higher education (in the following order: RO, UK, DE, US, UK). About every four years, I would pack up my things and move to a completely new place, to work with exciting new people and discover new places, and start all over. These moves felt perfectly ‘right’ at the respective times, and the goal has always been to learn more and seek the academic topics I was most passionate about.

“I am what you would call an academic nomad. Currently, I am a postdoctoral researcher in Geodynamics at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, but until now, I have made 4 international and institutional moves since I started my higher education (in the following order: RO, UK, DE, US, UK). About every four years, I would pack up my things and move to a completely new place, to work with exciting new people and discover new places, and start all over. These moves felt perfectly ‘right’ at the respective times, and the goal has always been to learn more and seek the academic topics I was most passionate about.Editor’s note:

Thanks to those who read the article till the end. I was inspired by a previous blog written by Irene, “The challenges (and the perks) of being academic nomads“. This time I wanted to prepare a blog with academic nomads from different parts of the world. In fact, I found people associated with all six habitable continents who have contributed to this article. Thanks to all my guest authors who spent precious time articulating their thoughts on this theme. A shout out to Trud Antzée for illustrating an amazing cover picture.

Finally, if you are lost in geography, here are the paths travelled by today’s authors.