Although often daunting and discouraging, every academic must navigate the inevitable process of peer review. In this week’s post, Jean-Baptiste Koehl, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo (Norway), reflects on what the future of peer review might be.

Author disclaimer: The reflections presented here reflect my perspective grounded in my own experience. While peer review is a key mechanism which we rely on to ensure the quality and integrity of scientific research, it has flaws and can perpetuate power imbalances and slow down progress. More on the mechanics of peer review in this post.

“Dear Editor,

I have never reviewed something like that. The author deliberately misinterprets the data published by others. The author claims that other authors provided statements that have never been provided. The author ignores tones of published works and sticks to his own only or only those that support his insufficiently documented and phantasy-driven models. It is needless to say that the author is neither a paleontologist, nor a geochronologist, while he is using both paleontological and geochronological record to pontificate his ideas unsupported by the published high quality data. Hence, this manuscript should definitely be rejected if [the journal] takes care of its reputation. This manuscript is clear evidence of ethical misconduct.”

Sincerely,

Anonymous reviewer

Does this sound familiar to you? Does it strike you as a constructive and fair review?

Let me tell you about a peer-review experience of mine. I submitted a manuscript to a journal in December 2022 that received positive reviews and a recommendation for publication pending moderate revisions, which I completed and resubmitted in 2023. Although one original reviewer approved the revision, a third anonymous reviewer’s negative report (see above) led the editor to reject the manuscript some months after. Why did the opinion of this one individual (the disgruntled reviewer#3) have more weight than that of the other three people involved (myself and initial two reviewers)? This didn’t sound fair and felt like a punch below the belt. We have known this for some time: peer review is biased and sometimes hurtful (e.g., Smith, 2006, Bharti et al., 2023). Anonymity is currently a standard feature of peer review models (e.g., double-blind peer review). However, anonymity can enable forms of writing or behavior that would normally be considered unacceptable and create imbalance and inequalities (e.g., Mavrogenis et al., 2020; Bharti et al., 2023).

The hidden imbalance behind anonymous peer review

Jean-Baptiste Koehl is a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Action researcher at the University of Oslo (Norway) and McGill University (Canada). His research focuses on the impact of orogens on rifting, planetary tectonics, the evolution of life, and the distribution of natural resources and geohazards using reflection seismic, structural fieldwork, geochronology, plate modelling, and machine-learning. He is involved in the GD and TS divisions and the EGU’s EDI taskforce.

Peer review can be compared to marriage counselling. Like marriage, it is a relationship between two individuals who are, hopefully, involved willingly. Nothing can be done if one side is unwilling to collaborate. Should there be disagreements, the only way to avoid parting is to work our differences out, e.g., by making compromises. One way to do this is via counselling with a mediator (journal editor).

Imagine going into marriage counselling, with the best intentions to find a solution to your conflict with a person you love and admire. But what if the mediator was only listening to your spouse and constantly pointing fingers at you? Would this seem constructive and fair? In most interpersonal conflicts, both parties play a role. At the very least, both parties are guilty of not having successfully found a compromise.

But what if you also realized that, instead of being an impartial third party, the mediator was your spouse’s high-school best friend or colleague? Or what if the mediator told you: “Sorry dear, I am only allowed to listen to your spouse”? You would end up with all the blame without having the possibility of voicing your side of the story, because there are always two sides to any given conflict. I guess you already see what I am getting at.

Peer reviewing is a double-edged sword. It plays a key role by providing an initial quality check on new research and helps connect the approach of tomorrow with established knowledge. Nonetheless, it can be constrained and slowed down by uneven reviewer practices often exerted by senior peers. How did we end up there?

peer review (…) can be constrained and slowed down by uneven reviewer practices

Let us back off a little and consider EGU’s General Assembly, where > 50% of the participants are early-career scientists (ECRs), an indication that a large share of new research is carried out by this group. Why are ECRs so often expected to defer to senior scientists? While experience is valuable, this expectation can often reinforce outdated hierarchical norms (“Look, I’ve been an ECR myself, so now it’s your turn”) rather than foster collaboration.

Instead of maintaining these rigid hierarchies, our community would benefit from empowering ECRs, who often bring strong expertise in emerging methods and technologies. We, ECRs, grew up using these technologies, learnt about them during our BSc, MSc, Ph.D., and postdocs, and spent time exploring with these tools, while our supervisors had only scraps of time (if any at all) to get acquainted with them. Recognizing and bringing these synergies together would strengthen the scientific community.

These power dynamics permeate all the way to the peer review process. Senior peers can feel empowered to cast stones from “under the cloak of anonymity”, sometimes making rude comments without an ounce of scientific argument, thus promoting arbitrary segregation instead of open and transparent scientific discussion. This is unfortunately not a new trend. Research has long demonstrated that anonymity leads to lower peer review quality and that many individuals simply decline to engage in peer review unless under the cover of anonymity (e.g., van Rooyen et al., 1999; Kowalczuk et al., 2015). In addition, many journal editors do not act as mediators but as bearers of bad news either because of (1) a misconception of the editor’s function and/or (2) journal’s policy, which may impede editors from acting against rude comments.

Despite these imbalances, many fellow ECRs support anonymous peer review, asking: “If I submit an honest critical review against a powerful researcher or research group, could revealing my identity harm my career?” These concerns highlight two issues: (1) some aspects of the peer-review system can reinforce hierarchical dynamics and (2) the option to remain anonymous discourages open and constructive dialog. As scientists, we should have the courage to voice scientific arguments and engage in scientific discussion, even if that discussion results in disagreement. Our diversities (e.g., background, skin color, beliefs, scientific hypotheses) are our greatest strengths!

However, two structural factors stand in the way of open disagreement: (1) senior researchers often have permanent and stable positions and (2) they influence career opportunities, which creates pressure for ECRs to remain cautious. These dynamics limit the exchange of new ideas, further enhance inequalities, sometimes resulting in unhealthy work habits, and slow down progress, often favoring “entrenched practices”.

As scientists, we should have the courage to voice scientific arguments and engage in scientific discussion, even if that discussion results in disagreement. Our diversities (e.g., background, skin color, beliefs, scientific hypotheses) are our greatest strengths

Furthermore, psychological biases also come into play. Although disagreeing should be acceptable (disagreeing = diversity = humankind’s greatest strength), it is often socially discouraged. Many people (especially senior scientists shaped by more authoritarian environments) struggle with feelings of inferiority or superiority (the latter of which is a feeling of inferiority in disguise; Adler, 1924). This feeling drives most (if not all) interpersonal conflicts, for example, when new ideas, approaches, and technologies provoke insecurity and threats in senior scientists, especially because being wrong equals being worthless and because Change requires additional time and energy. This could be understandable from a biological perspective but letting our basic instincts govern our behavior can be harmful to others and society at large. It is therefore important to recognize these biases and being mindful of others’ feelings and diversity.

Peer preview should encourage dialog. If an ECS feels unable to provide open, constructive feedback, declining the invitation is always a valid option. We must, however, have courage to get the dialog going, especially with those whose ideas we disagree with. We must have “the courage to be disliked” (Koga and Kishimi, 2013). Change takes all of us. So where do we go from here?

Towards a new peer-review system: the example of Open Research Europe

Dear objective fellow scientists, fear no more! There are several emerging alternatives to traditional peer-review systems, such as platforms that publish reviewer reports alongside manuscripts to encourage transparency and open discussion (e.g., EGU Copernicus journals). Another example is Open Research Europe (ORE), the European Commission’s Diamond Open Access Journal (free publishing and access for all; Figure 2).

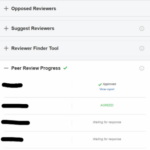

ORE uses an author-driven peer-review model in which reviewer identities are public and manuscripts receive a DOI upon submission, remaining openly available in all stages of the review process. Editors ensure format, ethics, and FAIR data compliance but do not evaluate the scientific content. Authors recommend reviewers and the reviewer status and feedback is displayed transparently (Figure 3). Once submitted, manuscripts cannot be rejected: they remain published regardless of peer-review outcome and can be revised in response to reviewer feedback, each version receiving a new DOI. This iterative model emphasizes the dynamic and aspect of scientific research (manuscript ≠ truth cemented in ink and paper, = forever maturing work in progress), thus encouraging the development of bold ideas, and reduces the need to split one’s work into multiple papers (AKA ‘salami slicing’), thus fostering quality over quantity.

Figure 2: Open Research Europe submission board showing the status of the reviewers and available features

Although currently limited to EU-funded research, ORE may expand its scope as early as mid-2026. While it is just one of several evolving publication models, it represents a promising step toward more transparent and inclusive peer-review practices. Change is coming, but it takes all of us.

If (un)like me, you feel that traditional peer-review systems are (in)appropriate, please do not hesitate to share your thoughts and opinion in the comments. Diverging opinions are essential to fueling a constructive discussion! 🙂

References Adler, A.: The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd, London, UK, 368 pp., 1924. Bharti, P. K., Navlakha, M., Agarwal, M. and Ekbal, A.: PolitePEER: does peer review hurt? A dataset to gauge politeness intensity in the peer reviews, Language Resources and Evaluation, 58, 1291–1313, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-023-09662-3 Koga, F. and Kishimi, I.: The courage to be disliked, Allen & Unwin, 288 pp., 2013. Kowalczuk, M. K., Dudbridge, F., Nanda, S., Harriman, S. L., Patel, J. and Moylan, E. C.: Retrospective analysis of the quality of reports by author-suggested and non-author-suggested reviewers in journals operating on open or single-blind peer review models, BMJ Open, 5, E008707, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008707 Mavrogenis, A. F., Quaile, A. and Scarlat, M. M.: The good, the bad and the rude peer-review, International Orthopaedics, 44, 413–415, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04504-1 Smith, R.: Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99, 178–182, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.4.178 Van Rooyen, S., Godlee, F., Evans, S., Black, N. and Smith, R.: Effect of open peer review on quality of reviews and reviewers’ recommendations: a randomized trial, BMJ, 318, 23–27, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7175.23