In 1995, the Caribbean Island of Montserrat was shaken by the beginning of one of the most significant volcanic eruptions in recent history: one that profoundly changed the natural, social and economical landscape of the country. Three decades later, Soufrière Hills Volcano and its legacy of destruction still shape the lives of Montserrat’s people. Last October, we took you on the first half of our journey to this remarkable island. Today, join us and the staff of the Montserrat Volcano Observatory on the second part of our reportage, as we explore the exclusion zone, have a close encounter with the volcano, and learn how, through so many challenges, the people of Montserrat are shaping their future.

Day 3: into the exclusion zone

Dr. Lorenzo Mantiloni is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Exeter in the UK. His research interests include the dynamics and stability of magma-mush reservoirs, approached with numerical models of stress and strain in poroelastic rock volumes, as well as modelling of stress and magma pathways in the Earth’s crust and volcanic hazard assessment. You can reach him by e-mail at l.mantiloni@exeter.ac.uk.

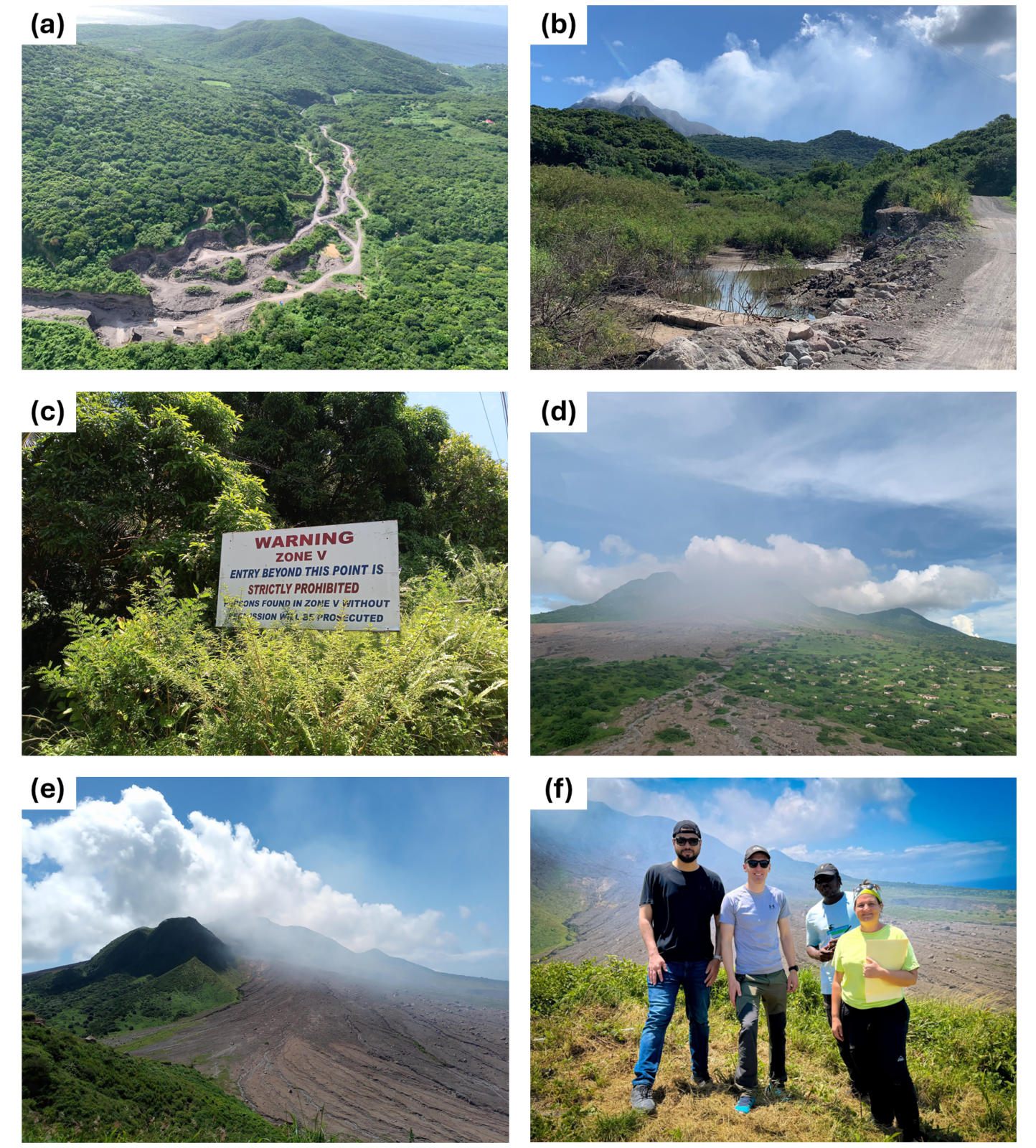

It’s our third day in Montserrat, and it’s time to venture into the exclusion zone. Karen and Racquel “Tappy” Syers – a Montserrat Volcano Observatory (MVO) scientific technician, and a genuine Montserratian – are our guides.

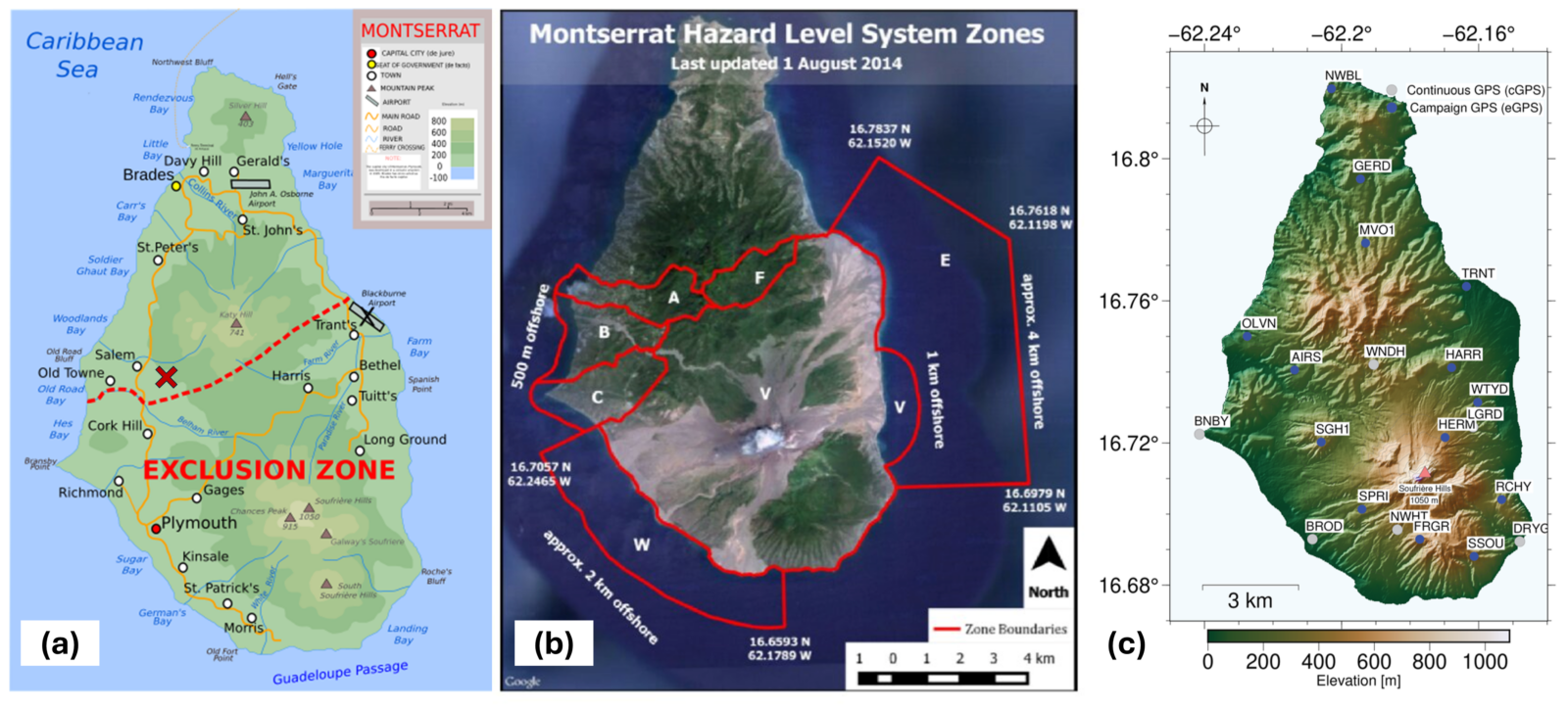

The island is divided into different risk areas, each with specific access restrictions (Figure 1b). Zone A begins just south of Salem, while Zone B stretches across the Belham Valley. These days, people live here in fully functioning communities. There is even a restaurant on one of the new beaches formed by volcanic sand accumulation after decades of lahars from the Belham River. In fact, the coastline has advanced considerably along all the southern part of the island, and it’s easy to notice it, with lines of younger trees marking the new land. The greatest hazard here is the Belham River itself (Figure 2a): despite being not a permanent river, it channels the water from heavy rainfalls and can lead to mud flows – although these now carry much less sediments than the lahars that swept the valley in the past. This is not the case now, but as we cross the river with our jeep, the driver points to what is left of a former 20-feet tall bridge, which now lies way below the road level (Figure 2b). The Belham River is also where the most exported product of Montserrat comes from: volcanic sand. Queues of trucks ply every day between the quarries along the river to the old capital, where the last functioning facility is a jetty waiting for the loads of sand to be shipped away.

South of the Belham Valley, we enter Zone C. People can live here too, as long as their house is completely self-sufficient – meaning that water and power are no longer supplied by the Government. The dusty road is well-maintained, but everywhere else it’s nothing but thick jungle. It takes me a while to notice the ruins of buildings, schools and fancy villas hidden in the overgrowth. This area was part of the limited access zone for a long time, but was only impacted by ash falls, and nature was free to take over.

Figure 1: meet Montserrat. a) Map of Montserrat with settlements and points of interest (credit: Wikimedia/Ivan25). Blackburne Airport, Plymouth and most of the villages within the exclusion zone were destroyed or made uninhabitable after 1995. The location of the Montserrat Volcano Observatory is marked with a red cross. b) Satellite map of the island, with the different risk zones outlined (Monteil et al., 2020). c) Map of continuous and campaign GPS stations operating on Montserrat as of 2023. Modified from Alshembari et al. (2024) [1]. a) and b) are repeated from Figure 1 and c) from Figure 3 of the first part of the reportage.

Figure 2: the exclusion zone. a) Helicopter view of the Belham Valley: the track of the ephemeral Belham River is visible, as well as the sand quarries and the “tiny” trucks (credit: MVO/K. Pascal, 2024). b) Into the Belham Valley: road skirting the Belham River. The rectangular structure just above the water is the top of an old, buried bridge (credit: MVO/K. Pascal, 2004). c) Entering Zone V. d) View of Soufrière Hills Volcano (SHV) and the ruins of Plymouth. The hilly neighbourhoods on the right were spared the flows that buried the rest of the town (credit: MVO Archives). e) View of SHV and the pyroclastic deposits from Fort Saint George (SGH1 station in Figure 1c). f) From left to right: Rami Alshembari, James Hickey, Racquel “Tappy” Syers and Karen Pascal (credit: R. Alshembari).

Finally, we reach the gate to Zone V on Saint George’s Hills (Figure 2c). Karen gets off the jeep and opens it to let us in. We are now in the real exclusion zone. Access is illegal unless authorization has been granted by the disaster management agency, but people with such clearance are quite diverse: sand mining workers, tourist guides and their groups, forestry department officials, and, of course, people contributing to the volcano-monitoring effort, as part of or in collaboration with MVO. Radio contact must be kept with the observatory at all times, and when night falls, gates are closed for everyone. For the rest, nothing has changed so far: everything is still covered in lush vegetation, and it’s clear that this used to be farmland.

Our first stop is a GPS station, SGH1 (Figure 1c), located on the hilltop, facing the South. From there, we get a spectacular view of the volcano, still hidden in its plume, the barren slopes and canyons and the petrified ruins of Plymouth, down to the extended coastline and the road to the jetty busy with sand-mining trucks. The town is divided into two halves: Plymouth’s hilly neighbourhoods are covered by still standing buildings, encroached by vegetation like anywhere else. The lower half, right on the path of flows coming from the volcano, is an ashy wasteland where little can grow. Most manmade structures are buried under metres of volcanic rocks and ash: a soil as hard as concrete. Here and there, the husks of taller buildings are still visible. That is our next stop.

Plymouth: don’t step on rooftops

The eruption started on July 18th, 1995, with phreatic explosions within the English Crater. It followed three years of increased seismic activity (Kokelaar, 2002 [2]) and the devastating Hurricane Hugo in 1989. On August 21st,1995, Plymouth was blanketed in ash and evacuated by the authorities for the first time. In November 1995, a dome started growing within the crater due to the slow ascension of highly viscous andesitic magma. The first pyroclastic flows were recorded in March 1996. By then, life on the island had been severely disrupted. In the following years, the dome kept on growing, collapsing and growing back. There were several explosive eruptions, and the associated ash falls, pyroclastic and debris flows repeatedly swept the countryside in different directions. Meanwhile, the south of the island was progressively being emptied of its people, though many were still refusing to leave their homes and fields. On June 25th, 1997, a partial dome collapse triggered pyroclastic flows that scorched vast swaths of land north-east of the volcano, destroying nine settlements and killing 19 people that had come into the exclusion zone, likely to take care of their home and animals. A few days later, more pyroclastic flows finally reached Plymouth, burning the town centre and the port. From then on, the dome underwent a cycle of build-up and collapses, with major episodes in 2003 and 2006. Finally, in February 2010, the last eruption to this date culminated with a massive collapse that buried what was left of Blackburne airport. No eruptive episodes have occurred ever since, but lahars and debris flows, as well as gas emissions, continue to pose an ever-present threat.

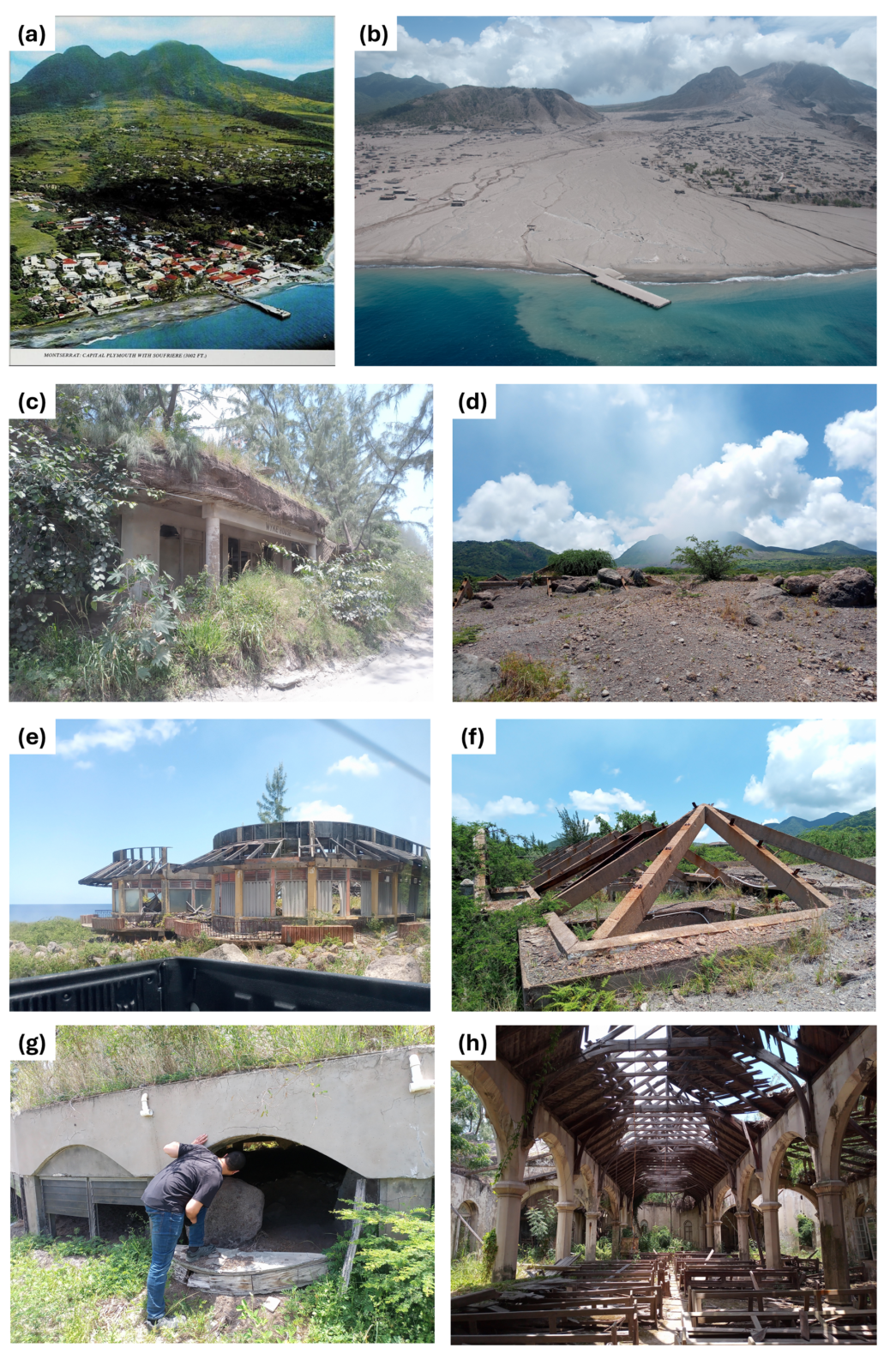

Figure 3: inside Plymouth. a) Plymouth, its harbour and Soufrière Hills Volcano (SHV) as they were before the eruptive crisis that started in 1995, as seen in an old postcard. b) Plymouth and SHV from a similar viewpoint to a), 15 years into the eruptive crisis, as they appeared after the February 2010 dome collapse (credit: H. Odbert, MVO Archives). Today, the jetty in a) and b) is the only part of the town that is still operating, excluding the guided tours in Plymouth’s centre. c) Condemned building along the road to the harbour. A thick ash deposit is visible on its roof. d) View of downtown Plymouth. Meters of pyroclastic flow and lahars deposits have partly of fully buried buildings. e) The upper floor of Arrow’s Manshop Store, owned by the internationally famous “Hot Hot Hot” singer. f) Concrete rooftops have stood the heat of the pyroclastic flows that buried buildings, one of the main hazards of the area. g) Rami peeking through the window of the buried Angelo’s supermarket, now resettled in the North. h) St Anthony’s Anglican church, slightly North of Plymouth center.

We enter Plymouth on the wake of a sand truck (Figure 3). There are new roads to move around, drawn over the buried town centre. Tappy, who is doing the driving, remembers how it used to look like, but can hardly relate the new landscape to his memories. We hit a few spots, stop for a few minutes and move again. A half-buried supermarket where you can peer through the first floor’s windows. A burnt roof skeleton, all that is visible of Barclay’s bank, which was robbed as the town had been evacuated in the first years of the eruptive crisis. More collapsed roofs around – it’s one of the hazards of the area: you don’t want to venture far from the road, lest you step on something ready to cave in.

Our last stop is St Anthony Anglican church (Figure 3h). Slightly north of the town centre, this area is not as buried as the other: there is only a shallow layer of dried compacted ash on the floor, like from some big concrete spill. The sunlight rains down the gutted ceiling. On the walls, plaques talk of people and lives from what looks like a distant past. It’s beautiful, in a disarming, haunting way. A graveyard is nearby, relatively unscathed, which means that the town’s departed are still there: in fact, many of the island’s lost ones are also lost to the exclusion zone. Graveyards, as much as schools, temples and venues, are the backbones of a community, and they, too, are missed.

Day 3-7: lasers, breadfruits, magical springs …

Figure 4: more of Montserrat. a) Isles Bay Beach Bar. The beach has been built by accumulated volcanic deposits transported by the Belham River after 1995. b) Old British coastal fort at Bransby Point (visible in a) in the distance). The cannons, brought by the English colonizers, have been rusting there for two centuries, and the ash falls from Soufrière Hills have risen the ground by several cm. c) Coconuts and other fruits on sale at Carr’s Bay. d) Roasted bread fruit: it will last me two weeks. e) Rendezvous Bay, North-West of Montserrat, the only white-sand beach on the island: only accessible via a hiking trail or boat. f) John Osborne Airport, and its new control tower, right before leaving the island on a 7-seats plane.

The days come and go, and I discover more and more about Montserrat, its volcano and its people (Figure 4). A few hours after our visit to Plymouth, Tappy and Karen initiate me to Electronic Distance Measurements (EDMs). The total station shoots a laser beam from our specific location to a reflector placed on the flank of Soufrière Hills Volcano and measures with high precision the time it takes for it to travel back, and hence the distance between the station and reflector (see Figure 3b in the first part of the reportage). Repeated and regular EDMs is one widely used method by volcano observatories to monitor ground motion. The day after, Karen takes us to Carr’s Bay, where people from the Rastafarian community often gather. They introduce me to a most amazing fruit: the breadfruit. Cooked on a wood fire, it feels like bread and tastes like mashed potatoes. I get instantly addicted to it. The whole island is full of fruits, from mangoes to guavas, to the cashew fruits, better known for their nuts. Food in general is quite delicious, as Caribbean, Indian and other traditions have mingled together. Tap water is good too, and fed by the fresh water from mountain springs – a true blessing for this part of the world. Legend has it that Runaway Spring near our place grants to those who drink from it the chance to return to Montserrat. James makes a stop there one night to ensure we comply.

… and the long wake of the eruption

Yet, for many in Montserrat, life is no paradise. Most food and goods need to be imported, meaning that they are scarce and expensive. Power outages are frequent. The island is virtually inaccessible during storms and hurricanes, and getting in or out of it in normal times is limited to air access and, again, very expensive. Young people who want to pursue higher education must leave the island, which is no easy feat, particularly due to economic reasons. Tourism, one important source of income prior to the eruption, remains, but has been strongly impacted and transformed: the ruins of Plymouth are a new, if dark, hotspot, and the island’s population and infrastructure cannot sustain as many visitors as before. The society itself has also been going through significant transformations. The unsettling and traumatic earlier years of the eruption, up to 1998, caused massive population displacements from the evacuated areas to the North of Montserrat, where some refugees decided to stay. However, up to 75% of the population emigrated, mostly to the UK, USA, Canada and to the sister Caribbean islands, even though many have been keeping a strong connection to the island, trying to come back periodically. Few did move back permanently, but the population growth, up to the present ~4,400 inhabitants (according to the 2023 census), is mainly due to immigration from other Caribbean islands. These new immigrants have helped rebuild the island, while changing the demography drastically and within only a few years.

As time goes on, a new divide is shaping up between those who knew the pre-1995 Montserrat and those who didn’t. Many of the former remember and often miss the lost capital, the lands in the South and a very different life, often with less struggles. Some people from the evacuated area say they sometimes dream about being in the lively streets of Plymouth, and of finally stepping back into the house they had to leave in emergency. In parallel, the younger generations or the newer residents, who have less or no attachment to the Montserrat that used to be, aspire to build on the existing communities in the North and develop a new, thriving society.

Today, even though the volcano left a scar on its people as much as its landscape and the island, with a population half smaller, is much more dependent on UK financial support than 30 years ago, Montserrat’s future is slowly taking shape. Constructions sites of an improved harbour, hospital, and tourism facilities testify how the rich history of this land is not over, no matter the challenges it faces.

In this context, as responsible for volcano monitoring and advising decision makers for matters related to volcanic risks, the MVO sits in a crucial but delicate position. And while the MVO has no actual saying in government decisions, we briefly got an idea of the pressure it could sometimes face, when we participated to a radio interview at ZJB, the government and only radio station. Indeed, as we had just settled in the little recording studio, without much of an introduction, our host, Winston “Kafu” Cabey -who became volcano radio-reporter in the early years of the eruption- throws at us: “Well, it’s been 14 years and running since last eruption. When are we going back to the South?!”

Kafu’s question has no easy answer. In the exclusion zone, the potential for eruptive activity still looms. Even if Soufrière Hills Volcano is relatively quiet at the surface, it is still active, and the issues it brought, in terms of access to the land and its resources, will not disappear in the foreseeable future, at least as long as the UK and the local government keep their current approach to volcanic risk management.

Day 8: up in the air and close with the volcano

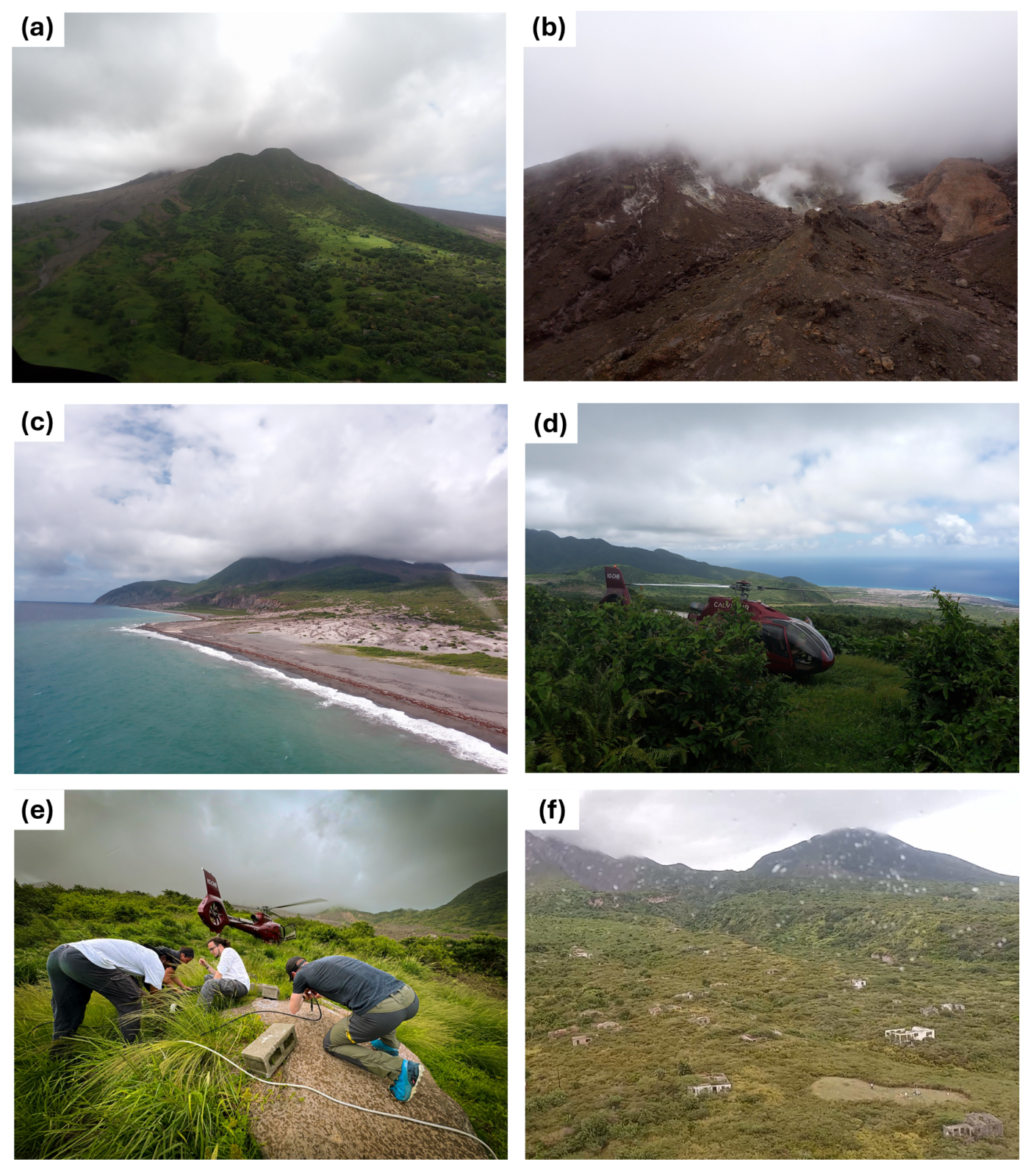

Figure 5: Volcano-monitoring with a helicopter ride. a) Approaching Soufrière Hills Volcano. b) A close view of the dome and its fumaroles. c) Flying over Spanish Point, near the site of former Blackburne airport. The cliffs mark the extent of the old coastline. d) Landing area at a GPS station. e) Getting a GPS survey station ready (credit: R. Alshembari). f) Southern neighourhoods of Plymouth. One of our landing areas is visible on the bottom-right corner.

It’s our last day in Montserrat and, being also the MVO field-work day when access to most monitoring stations is only possible by helicopter, it brings me a final thrill: a helicopter flight above the volcanic landscape. It’s my first time ever in a helicopter, and I’m just a tiny bit scared. We are taken along by MVO staff Adam J. Stinton, Karen and Tappy to collect visual, GPS and EDM data around the volcano flanks. We take off from the helipad next to the Observatory, and I am in awe as we cruise above the ruins of villages, farms and hotels close to the Belham Valley, then onward to Soufrière Hills, approaching the massive dome, its spewing fumaroles now visible under the curtain of clouds and gas (Figure 5). Further on, the now ashy desert that used to be the island’s main airport; the cliffs of South Soufrière Hills, still lush and never quite inhabited at all; the rough Chances Peak, once the highest peak of the island before being eclipsed by the new dome that lays onto it, and, finally, Plymouth again.

Each time we land at a site, the helicopter waits for us with the engines on. The landing areas next to the GPS stations must be cleared of vegetation on a regular basis, as grass being sucked into the helicopter’s rotors can be disastrous: this is the job of special teams of local “bushers”, that are dispatched in the field on dedicated flights and know how to skilfully jump out of the hovering helicopter with machetes. At each GPS station, we try to be as quick as possible while undertaking various tasks: data collection, battery change, and keeping plants at bay. We even deploy a GPS survey station with Karen and Tappy. Another station has a bucket next to it, collecting rainwater: as Adam explains to us, its pH is a proxy for the SO2 content of the plume. This is daily routine for our hosts, and as far as it gets from my academic comfort zone: while I try not to mess up some very expensive equipment or have my head chopped off by the helicopter’s blades, I feel quite clueless. The whole experience is both chilling and breathtaking, and as I’m closer than ever to the fuming giant, I feel grateful for being there.

Day 9: leaving the Emerald Isle

The next morning, we are back to the new island airstrip where it all started, but this time carrying hot sauce and lots of memories with us. We say goodbye to Karen and the rest of the MVO team and, as the tiny plane takes off again, I greet the island too, before the clouds hide it all. I can’t tell the impression this place left on me without sounding cheesier than I’ve been so far. It’s enough to say that, for the first time, I realise that my work doesn’t just satisfy my scientific curiosity and takes me to interesting places, but can also have a real impact on people’s lives, well-being and future. I feel useful. It’s nothing comparable to the work of volcano observatory staff, which can be risky and requires to engage with people regularly, and it’s far from the research experience of my seniors; nonetheless, it’s something worth being aware of.

I dedicate this post to the MVO staff, to their dedication and resourcefulness, and to the kind and enduring people of Montserrat. May your Emerald Isle thrive once more. I also wish to thank my supervisor James Hickey and my colleague Rami Alshembari for bringing me to this both haunting and beautiful corner of the world.

The first part of this reportage was published on EGU Blogs – Geodynamics on October 9th, 2024. The (brand new!) website of the Montserrat Volcano Observatory can be found here. They are very active on social media as well. The University of the West Indies Seismic Research Centre also provides information on the island and the volcano. ZJB Radio, Montserrat’s only radio station, has its own website. The DV3M project at the University of Exeter is described here.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the start of Soufrière Hills eruption. To commemorate this event, the Montserrat Volcano Observatory is organising the SHV30 conference in July 2025.

References: [1] Alshembari, R., Hickey, J., Pascal, K., & Syers, R. (2024). Declining magma supply to a poroelastic magma mush explains long-term deformation at Soufrière Hills Volcano. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 631, 118624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2024.118624 [2] Kokelaar, B. P. (2002). Setting, chronology and consequences of the eruption of Soufrière Hills Volcano, Montserrat (1995–1999). https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.021.01.02