We live in a society where climate change has already shown its impact across the world with devastating consequences. The alarming frequency of extreme weather events leading to tremendous disasters leaves us all perplexed and anxious about what will be coming next without taking any immediate action. Bearing that in mind, Dr. Joshua L. DeVincenzo with M.A Student Syeda Kainaat Jah both from Columbia University will delve into elaborating on how we can educate and engage more people from all walks of life in terms of understanding the climate impacts and the importance of implementing effective disaster risk reduction strategies.

Dr. Joshua L. DeVincenzo is the Assistant Director for Education and Training and Lecturer at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness, Columbia Climate School, Columbia University, and holds a doctorate in Education from Columbia University Teachers College. He develops educational programs on disaster preparedness and climate literacy and has published extensively on climate pedagogy and cognition. You can contact Joshua via e-mail or on LinkedIn.

Climate and Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) work has always been what I have come to refer to as one of the “Good Luck Disciplines.” Routinely, when one describes what one does or what one’s research entails, it is often met with “That’s Important” or “Interesting,” followed by the inevitable, “Good luck with that.” As much as the encouragement for this work cannot be understated or more appreciated as the field becomes more complex and on display, disaster risk reduction has always called upon the whole of society or whole community inclusive approaches to be indeed effective. At the present moment, we need more and more people to engage in themes of understanding climate impacts and disaster risk reduction strategies. Therefore, critical questions emerge on how we, as a research and practice community, authentically bring in all of society and the whole community? How might we transition from good luck to good intentions to get engaged?

As we are well aware, leaving disaster to only luck or chance is not a viable option as the increased severity and intensity of disasters continue to germinate and disrupt communities around the world with a new risk landscape that has become less predictable and more consequential. Based on social and behavioural sciences, my research in the field has focused on precisely this challenge of democratising climate and DRR information in meaningful ways. The stakes are too high and costly to learn by doing in a reactive fashion. However, focusing on a collective agency toward disaster preparedness and resilience is well within reach if intention, attention, and empowerment are invested (Johnston et al., 2022).

I will share some observations from working on climate education with learners ranging from secondary school students to those seconds away from retirement. Before I do, I wish to emphasize that climate and DRR learning is a continuum and a true case of lifelong learning; we have made great strides in recent years, and that momentum presents wonderful opportunities for expansion and growth. Should we make the call to action accessible, inclusive, and achievable, the potential for progress in our field is immense.

Kainaat Jah is a Graduate Research Assistant in the Education and Training division at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness, where she manages and designs training programs, and assists with cross-team coordination and grant proposals. She holds a BSc in Political Science from the Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. Currently, Kainaat is pursuing an M.A. in Anthropology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. You can contact Syeda Kainaat via e-mail or on LinkedIn.

Experience: The Low Hanging Fruit

We are often asked by learners, ‘What do I really need to know?’ or they express, ‘I am not a climate scientist, nor do I want to be one.’ Both commentaries are more than fair and have a balance worth expanding upon. For one, we live in an information-rich world with a new power to curate the information we are exposed to. This unique affordance of technology allows us to toggle our attention to whatever information wins in the bidding war on our devices, as well as the literal bidding war behind the scenes for our engagement, support, and beliefs. However, if we leave our engagement and beliefs to our own devices (literally), we miss the data density of primary experience and the learning that can occur from human-to-human experiences and communication. Howarth et al. (2020) emphasised the value of diverse knowledge systems in climate communication, arguing that storytelling can bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and public understanding, making complex climate concepts more accessible and relatable. Thus, the value of human-to-human learning cannot be overstated, especially when it comes to facilitating intergenerational dialogue on climate change and disasters.

Each generation brings a unique perspective and knowledge, and it is through these conversations that we can truly understand and address the challenges we face. One way I have seen this play out is by addressing the tremendous cognitive challenge of causal reasoning with climate change. In short, this challenge involves agreeing on why climate change is occurring (cause) and what is happening because of it (effect). Each generation holds a key to this connection, whether they are aware of it or not. It is not uncommon to hear in climate discourse that either the responsibility now falls on the younger generations or that the older generations are leaving climate change to capable hands and staying out of it. As a result, Alvi et al. (2023) found that younger generations’ prioritisation of mitigation efforts over their older counterparts is attributed to their greater awareness of long-term impacts. However, approaching the climate crisis this way discounts the importance and value of human-to-human learning. Suppose we return to our climate causal reasoning paradox and the keys we carry. In this case, we can leverage human experience to fill critical cognitive gaps on either side of the cause-and-effect equation. Older generations have a wealth of lived experiences, in which, regardless of their scientific understanding or beliefs, they can pinpoint key events such as extreme weather events, changes in how they experience seasons, shifts in expectations year to year, or, as one of my former research participants has clearly stated, when “something’s up.”

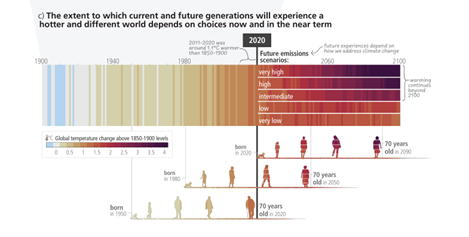

Older generations hold with them a key to archives through their experiences of the impacts of climate on communities and livelihoods. Using storytelling as a powerful tool to build resilience by connecting personal experiences with broader community efforts (McEwan et al, 2017), they can illustrate this history along with what went well in past events and what drastically must be improved upon for future events. In many ways, they can provide a valuable context for the “effect side.” Whereas younger generations, thanks to improvements spanning climate curriculums, scientific advances, and new innovative ways of engaging in climate science, have grown expertise in understanding the causes of climate change. Younger generations have leveraged this knowledge to lead some of the most impactful campaigns of recent history to address the issue at its many sources. Naturally, younger climate learners do not have the same level of experience as their more seasoned counterparts but hold a valuable key to articulating cause. In a beautiful exchange, older generations can share their experiences in ways that can complement the younger generation’s learning continuum on climate and, in return, complete their knowledge of climate reasoning through lessons learned from the younger generation on the latest science, policy, and movements. One of the best illustrations of this dynamic comes from the UN IPPCC’s AR6 visual, which shows the extent to which current and future generations experience a hotter and different world.

This figure from figure SPM.1 in the United Nations IPCC’s AR6 Synthesis Report shows the observed and possible projected global temperature trends and how they would impact different generations. (Image: UN IPCC)

Regardless of generation, we have an abundant repository of previous disaster events, data, analysis, news coverage, and case studies. Yet, we often discount the power of primary experiences—those that we have lived through in our lifetimes or that have left such an impression on us or people we know that they have been committed to memory. As our data becomes more precise and innovative in the field, the stories of disaster survivors become more vivid and more frequent. This juncture is a crucial opportunity to democratise climate and DRR education to expand knowledge of what is occurring and how it is occurring, especially if the barrier to entry is for most of part one’s lived experiences.

Finding a place in the system:

Next, I’d like to discuss the importance of, both scientifically and socially, supporting learners in their journey to situate themselves in the system dynamics of climate change. After we know what is going on and how it is happening, we often scaffold learning into understanding how climate change and DRR work as a system of interconnected and interdependent parts. This idea has been popularised and widely adopted as a form of systems thinking. However, it is not always so clear for learners where they are in this system or if they are part of it at all. This situation is where, in climate and DRR, we might get a quick “good luck” and exit from people. This situation is also where the challenge arises: “How can I expand the system enough where a learner sees where they are? And in doing so, illuminate where they provide key value to climate solutions?” Much of this stems down to how accessible we make this information and the agency we convey to individuals and organisations to feel confident in their abilities and resources to be included.

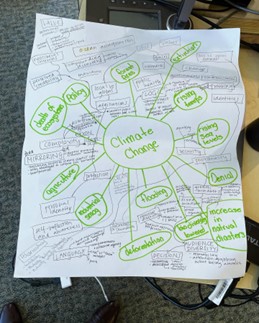

One way to achieve this is to visualise everything that comes to mind when one thinks of climate change (See below for an example from a recent High School workshop on Climate Change and Disasters). From there, it is emphasised that our “mental model” is dynamic: it constantly changes with new information and must be updated. Participants are then encouraged to add new information throughout the lecture, whether it is topics or connections between concepts. Additionally, the more ideas that stem from the root that are added, the more ways people begin to see themselves or draw connections to what might be familiar- contextualising seemingly distant disasters and climate concepts. Learners begin to see causal reasoning but can also chart ways to address the issues from several angles.

An example from a recent High School workshop on Climate Change and Disasters. (Image: Joshua L. DeVincenzo).

A critical aspect of this exercise is to highlight the importance of combining empirical evidence with lived experiences, which become clear in how someone approaches their mental model. It depicts the uniqueness of human knowledge and behaviour regarding themes of climate and disasters. It also introduces the challenges, as there is no singular or dominant mental model, and learning must adapt to the variability we find with climate learners.

Sometimes, learners may feel overwhelmed by the system-thinking approach to climate change due to a new layer of complexity and its chaotic interaction of parts. In my teaching, I try to alleviate some of this by likening the climate system to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Like the climate system thinking approach, the MCU has intricate plots, the introduction of new characters, overlapping and contrasting storylines, and spans for long periods of time. However, for many, the MCU is intriguing, and they find joy in distilling its system elements down and even forecasting what is to come in the release of the forthcoming films. In a recent workshop, I proposed the question after showing a side by side of a climate change systems chart and an MCU movies chart, “What makes climate change different than the MCU”? After a pause to think, students shared their profound input. One student mentioned that the MCU is more entertaining, and another noted that in the MCU, we get to watch and enjoy the film, know who the heroes are, and that they usually win in the end. Just as fans analyse and predict MCU plotlines, we can use system thinking to understand and address the complex web of factors contributing to climate change. Regardless of complexity, whether it is MCU or climate, the human capacity for complexity is an incredible thing. One that we should not discount as we further try to democratise climate and DRR education. Embracing this complexity can empower learners to engage more deeply and meaningfully with the challenges of our time.

Time:

Climate change and disasters cannot be limited to a single snapshot in time. So, I would be remiss not to mention the importance of temporality on climate change and DRR education. From my research into adult climate literacy, which focused on emergency managers and their approach to climate challenges, the findings alluded to the need for enhanced capacity in long-term thinking as well as thinking across timescales. In each of the approaches we discussed, intergenerational dialogue and system thinking approach to climate change, we can better address this challenge. To do so, we can turn to the Recovery Continuum, where we have shifts in both experience and system elements in the case of a disruptive event. Most importantly, the continuum challenges us to think of climate impacts as more than the event itself but also to consider the context leading up to the disaster and events following across days, weeks, years, and even decades. Through this understanding, learners can better exercise temporal dimensions with climate and disaster recovery through both lived experiences and foresight capability to increase community resilience. This is a transitory process wherein the notion of climate change as scientific or theoretical brings its themes into reality in concrete, actionable, and direct ways.

Conclusion:

I suppose we are, in fact, going to need a lot of luck. But, if that luck can be coupled with individuals and communities that can access and be empowered by climate and DRR information, it may make all the difference. Perhaps we don’t need everyone to be a climate scientist or disaster expert or to take on all the planetary challenges we may see in a group mental model. But if we can create learning that can assist someone in supporting the world around them, whether formally in schools or organisational learning or informally, through stories and discussion with friends and family, we can better situate ourselves on a climate learning journey and system that is constantly changing. This collective approach highlights that the burden cannot fall only on individuals; our institutions must also undergo a similar learning process in which we can create an ecosystem that is equipped for the climate challenges and opportunities ahead.

References Alvi, S., Salman, V., Bibi, F.U.N. and Sarwar, N. (2023). Intergenerational and intragenerational preferences in a developing country to avoid climate change. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1098382. Howarth, C., Parsons, L. and Thew, H. (2020). Effectively Communicating Climate Science beyond Academia: Harnessing the Heterogeneity of Climate Knowledge. One Earth, 2(4), pp.320–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.04.001. Johnston, K.A., Taylor, M. and Ryan, B. (2022). Engaging communities to prepare for natural hazards: A conceptual model. Natural Hazards, 112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05290-2. McEwen, L., Jones, O., & Robertson, I. (2017). "Understanding Narratives of Flood Risk and Resilience: Exploring the Protective Role of Storytelling." Geoforum, 79, 106-116. McEwen, L., Jones, O., & Robertson, I. (2017). "Understanding Narratives of Flood Risk and Resilience: Exploring the Protective Role of Storytelling." Geoforum, 79, 106-116.