As geoscientists, we tend to see geology everywhere. Around Christmas, many people stare at decorated fir trees and twinkling lights; salt tectonicists stare at seismic lines and outcrops and see… trees as well. Tall stems, branching limbs, stacked “tiers” of material; a whole forest of geological Christmas trees hiding in the subsurface.

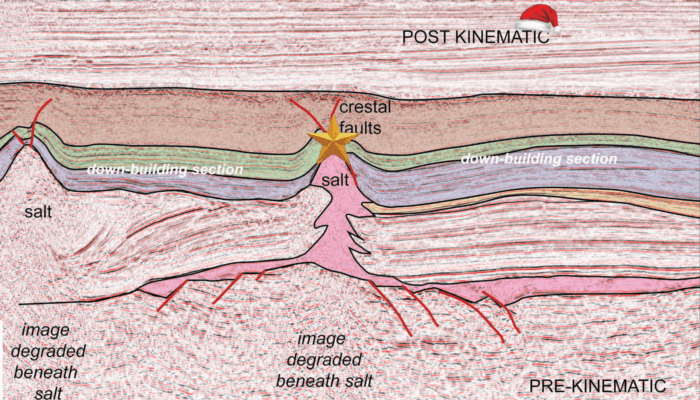

In salt provinces around the world, from the Flinders Ranges in Australia to the South Atlantic margins and the Central European Basin, geologists have described “Christmas-tree structures” in salt (or mud, but today we will center our wishes in salt). The nickname looks informal, but the geometry is real: vertically organised salt bodies with multiple stacked branches of salt and sediment that together resemble a stylised fir (Figure 1).

It’s time to set out our Christmas-tree (Figure 1), decorate it, turn on the shiny lights and put our start on the top. Let’s make our salty Christmas tree so cool that Santa will be proud enough to leave a few gifts under it.

What do we mean by Christmas-tree structure?

In geology this name can refer to multitude of things, but most people use “Christmas-tree structure” for salt systems that share three features:

- A relatively narrow “stem” of salt at depth, typically a diapir or feeder from a basal evaporite layer.

- A set of vertically stacked “branches” that widen upward: salt glaciers, concordant intrusions, minibasins and welds that step from side to side. Generally we can call those branches “salt wings” (Jackson & Hudec, 2017).

- A multi-phase evolution in which salt repeatedly rises, extrudes or intrudes, and is then is buried and reactivated.

In cross-section, the whole system looks like a tree: narrow trunk, wider crown, several asymmetric branches. Classic examples include:

- The Neoproterozoic “Christmas tree diapirs” of the central Flinders Ranges (South Australia) (Figure 2), a steep diapiric stem feeds stacked salt-glacier tongues and associated minibasins (Dyson, 1999).

Figure 2: Slumping at the base of the salt glacier; sedimentary facing is to the right Flinders Ranges (South Australia) (Dyson, 1999).

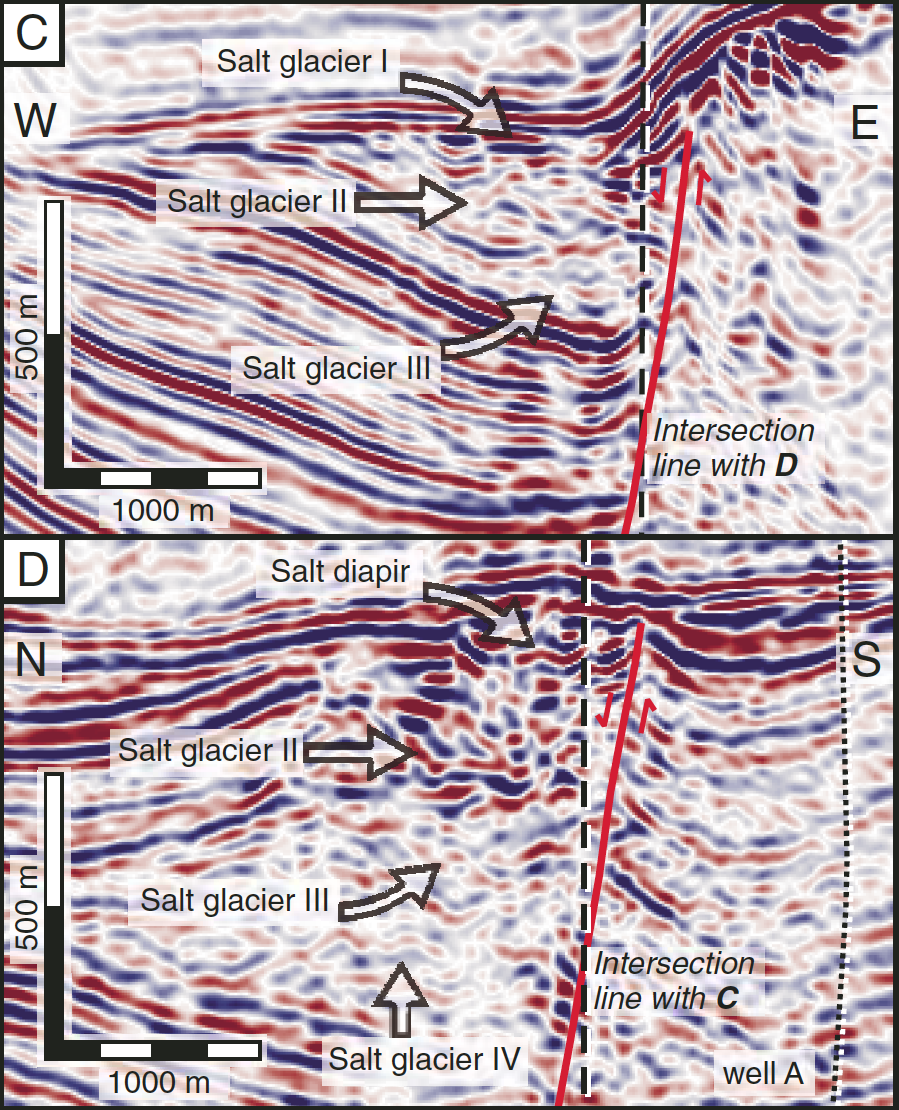

- Late Triassic salt glaciers (namakiers) systems in the NW German Basin (Figure 3), 3D seismic data reveal a tiered set of salt glaciers extruded from a near-emergent Zechstein diapir (Mohr et al., 2007).

Figure 3: Seismic sections showing salt glacier generations and salt diapir, and accompanying sedimentary layers in NW Germany (adapted from Mohr et al., 2007).

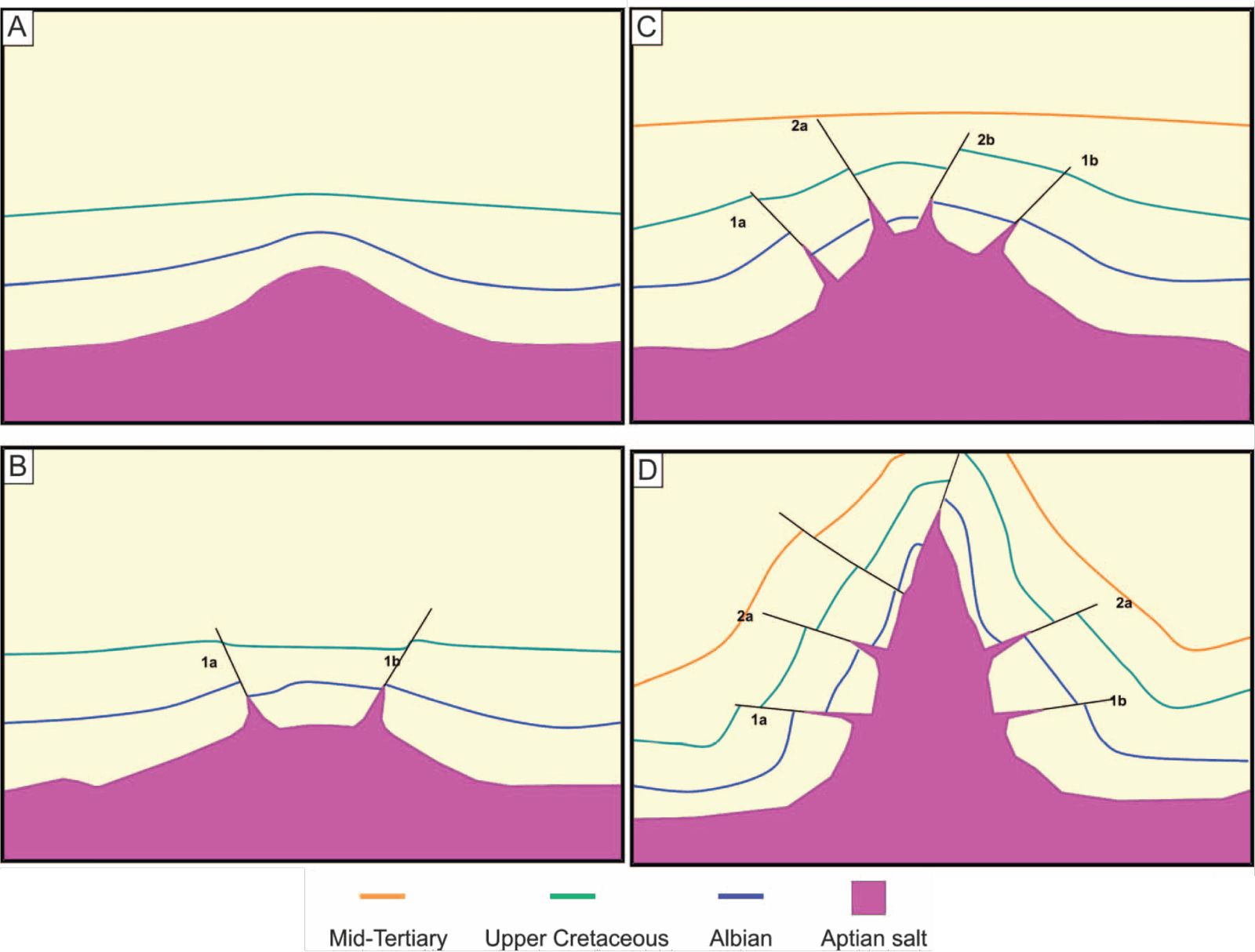

- Halokinetic rotating-fault systems offshore Brazil, salt intrudes along crestal faults and bedding, creating tree-like stacks of concordant salt sheets around a diapir core (Figure 4) (Varela & Mohriak, 2013).

Figure 4: Schematic evolution of a salt diapir with halokinetic rotating faults: a salt dome first develops, then a crestal collapse graben forms with extensional faults that guide initial salt intrusion. As deformation continues, these faults migrate to the diapir flanks, rotate to lower dips while bedding steepens, and new crestal faults appear. Ultimately, subhorizontal faults with steep bedding and intrusive salt stringers produce a “Christmas-tree” geometry, with some apophyses later squeezed back into the diapir or dissolved (adapted from Varela & Mohriak, 2013).

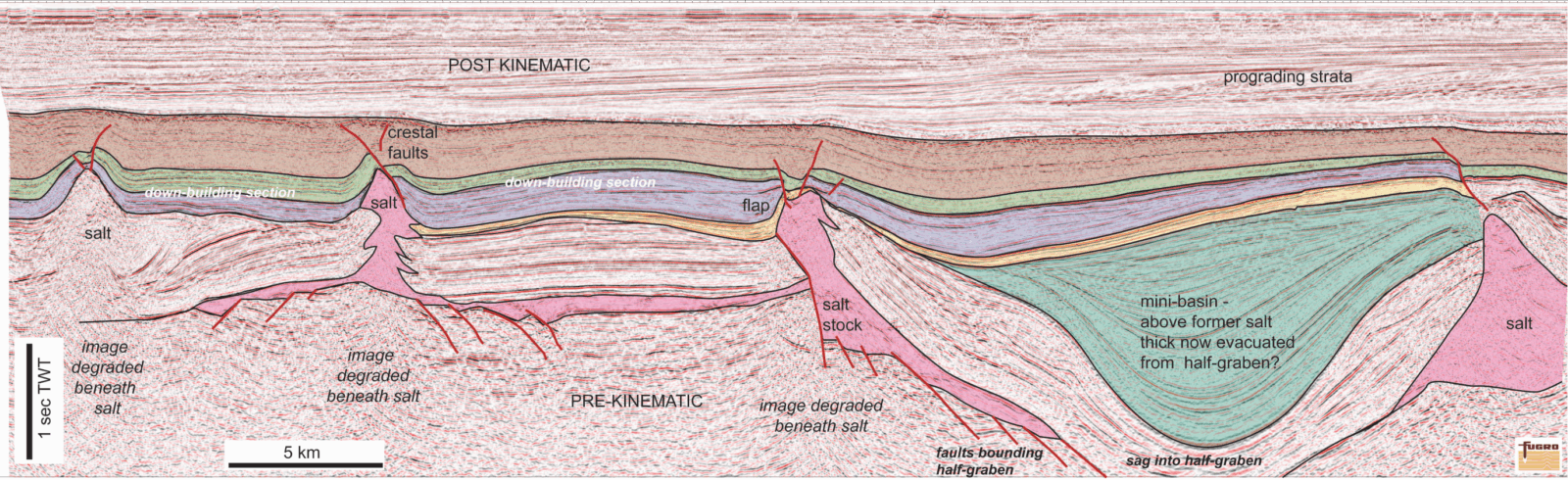

Despite the diversity of settings, the common image is a vertical pile of salt-related features, all rooted in the same source layer and recording a long, episodic history of salt mobility (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Regional profile through salt structures in the eastern part of the Dutch graben, southern North Sea (Butler, 2022).

What do you need to grow a geological Christmas-tree?

Growing a Christmas tree out of salt instead of wood requires a familiar set of ingredients:

- A weak salt layer: Most examples involve thick halite-dominated evaporites with low density and low viscosity compared to their siliciclastic or carbonate overburden. This density inversion makes the system susceptible to Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities: salt wants to rise, overburden wants to sink (as we want to sink our Christmas cookies in hot chocolate).

- Differential loading and/or tectonic forces: Salt does not move because yes. It responds to different variations.

- Lateral variations in sedimentation and erosion that create minibasins and zones of differential loading.

- Regional extension or shortening that localise faults, tilt strata and focus flow into walls, stocks and diapirs.

- A pathway from source to shallow levels: Small perturbations at the salt-sediment interface grow into pillows, then walls, then diapirs (the circle of life). Once a diapir gets close to the surface, it becomes much easier for salt to extrude as a glacier or to intrude along crestal and flank faults

- Repetition over time: Christmas-tree structures are almost never single-event features. They record multiple episodes of salt upwelling, extrusion or intrusion separated by phases of sedimentation, burial and sometimes erosion, shortening or quiescence without strong salt movements (Maystrenko et al, 2010), a life full of changes.

The relative balance between upbuilding (the diapir rises into aggrading strata) and downbuilding (overburden subsides while salt remains pinned near the surface) controls whether a diapir repeatedly breaks through and feeds new branches, or spends long intervals buried and quiescent.

From seedling to full tree

Different basins add their own complexity, but many Christmas-tree salt systems follow a similar storyline.

- Reactive stage: Small thickness variations, basement relief or early faults perturb the salt-sediment interface. Under differential loading, these perturbations amplify into reactive pillows and then into incipient diapirs. Syndepositional growth strata start to form minibasins on either side. At this stage, the geometry is still a simple stem with two modest flanks – our tree seedling.

- Passive diapirism and approach to the surface: Continued sedimentation on the flanks and continued salt inflow into the diapir lead to passive diapirism. The diapir more or less keeps pace with aggradation in the minibasins and approaches the surface. The crest of the diapir is mechanically weak and commonly develops small grabens and steep normal faults. These crestal faults are critical: they are the future pathways for salt to intrude or extrude and will later rotate into the flanks as halokinetic deformation proceeds (see Figure 4).

- First branch, extrusion or intrusion: Once the top of the salt body reaches very shallow depth, two endmember behaviours appear:

-

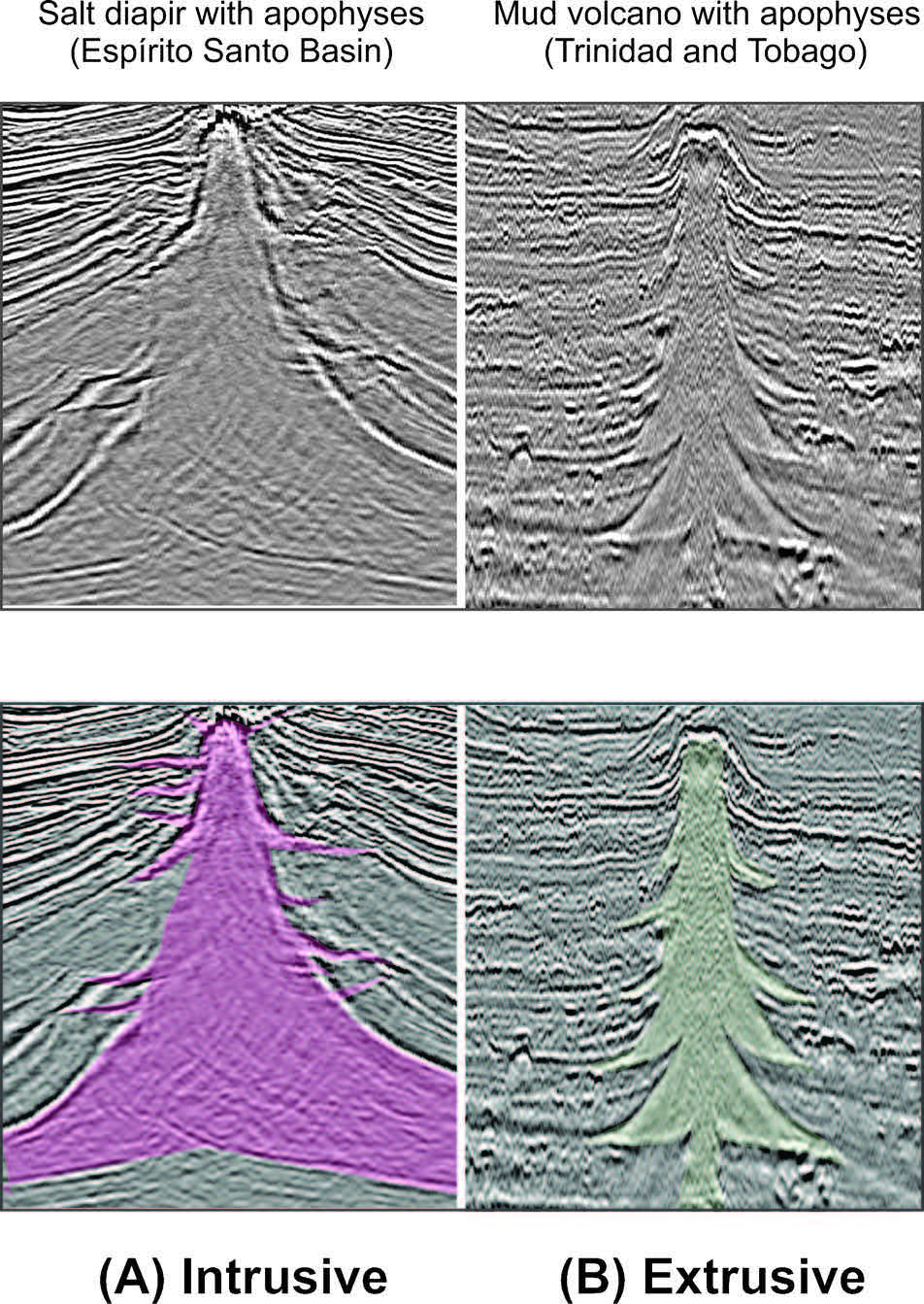

- Intrusive branch: If salt remains just below the surface or if the overburden contains favourable weaknesses, it can “intrude” along crestal or flank faults and along bedding-parallel horizons (Figure 6A). These intrusions tend to be concordant with stratigraphy and appear in seismic data as gently curved sheets branching off a central stem.

- Extrusive branch: If the diapir breaches the surface in a subaerial or very shallow subaqueous setting, it can feed a salt glacier (namakier). This tongue of salt flows outward under gravity, is reworked by dissolution and erosion, and is eventually buried (Figure 6B). The central diapir acts as a feeder, analogous to a volcano feeding lava flows, but with slightly less dramatic fireworks.

Figure 6: Seismic comparison between intrusive (discordant) salt structures and Christmas tree structures (concordant apophyses of salt or shale). (A) A salt diapir in the Espírito Santo Basin (interpreted as an intrusive feature). (B) A mud volcano in Trinidad and Tobago (interpreted as an extrusive feature) (Varela & Mohriak, 2013).

Either way, the once-simple diapir now has its first recognisable branch.

- Halokinetic rotation and migration of faults: As sedimentation continues, minibasins deepen and the diapir crest subsides relative to its flanks. New crestal faults form, while older ones are progressively rotated and advected towards the flanks by halokinetic flow. The halokinetic rotating-fault model of Varela & Mohriak (2013) captures this process:

-

- Newly formed, high-angle crestal faults may be intruded by salt.

- Older faults rotate to shallower dips and migrate into the flanks, carrying earlier intrusions with them.

- Growth strata thicken into hanging-wall depocentres, producing characteristic wedge geometries and internal unconformities.

Repeated through time, this fault–intrusion–rotation cycle builds a tiered set of salt sheets and associated growth wedges. In cross-section, those sheets stack into a tree-like pattern: young, steep branches near the crest; older, rotated branches lower down the flanks.

- Stacking branches and minibasins: In systems dominated by extrusion, the diapir can go through multiple cycles of near-surface breakthrough, salt glacier emplacement and burial. Mohr et al. (2007) documented such behaviour in the Triassic of NW Germany, where several generations of salt glaciers are preserved as a vertical stack. Each tier reflects a different balance between salt supply, sedimentation, topography and climate.

In systems later affected by shortening, such as parts of the Flinders Ranges, pre-existing diapirs, minibasins and salt-glacier remnants can be folded and thrusted. Diapirs may weld at depth while still feeding limited lateral flow; minibasins may “step” from one side of the structure to the other during progressive deformation. The end result is again a vertically organised, multi-tiered system with a strong zig-zag or tree-like geometry.

Three flavours of Christmas-tree salt systems

Because the “Christmas tree” label is descriptive, it is useful to distinguish a few idealised types that emphasise different processes.

- Extrusive stacks of salt glaciers (namakiers):

These systems are dominated by surface or near-surface salt flows:

-

- A diapir repeatedly reaches or nearly reaches the surface.

- Each episode feeds a salt glacier that flows downslope, is partially dissolved or eroded, and is then buried by sediment.

- Subsequent reactivation produces new glaciers above the old ones.

Vertical stacking of these lobes, separated by sedimentary packages, produces a tiered Christmas-tree geometry. The Keuper salt glaciers system of Mohr et al. (2007) is a clear subsurface example, Neoproterozoic glacial-related minibasins and salt tongues in the Flinders Ranges provide an outcrop analogue of stacked extrusive branches (Figure 6B).

- Intrusive, concordant Christmas trees:

Other systems are dominated by intrusions along faults and bedding within the overburden:

-

- Halokinetic rotating faults at the diapir crest and flanks provide low-pressure pathways for salt to intrude.

- Internal overpressure within the salt or regional compression can further drive salt into these weaknesses.

- The resulting sheets are broadly concordant with bedding and form gently curved branches emanating from the diapir core.

Because these branches may be thin relative to seismic resolution, they can be confused with younger evaporitic layers or even with non-evaporitic units. Varela & Mohriak (2013) emphasised this risk of “seismic pitfalls” when interpreting layered salt bodies and highlighted the need to distinguish true stratigraphic evaporite packages from intrusive trees of salt sheets (Figure 6A).

The use of term intrusion can lead to confusion, salt doesn’t intrude as a igneous rock, it flows, the correct term should be “salt delamination”, but to keep it simple l’ets use intrusion (Grzybowski & Krzywiec, 2019).

- Weld-dominated and compressional Christmas trees:

In some fold-and-thrust settings, pre-existing diapirs and withdrawal minibasins are shortened and welded:

-

- Diapirs may evolve downward into complex welds, detachments and thrusts while retaining some lateral salt flow at shallower levels.

- Minibasins can migrate and stack, forming a vertical array of depocentres separated by welded salt limbs.

- The combination of welded stems, flanking thrusts and stacked basins again produces a tree-like outline in cross-section.

Why should we care about Christmas-tree salt structures?

Beyond the fun name, seasonal relevance and my love for salt tectonics, these structures matter for several reasons.

- Stratigraphic and paleogeographic archives: Each branch or tier captures a specific episode in the life of a basin:

-

- A phase of salt mobility with particular boundary conditions (tectonic regime, sedimentation rate, climate, water depth).

- A corresponding package of clastic or carbonate strata in adjacent minibasins, recording changes in accommodation, subsidence and sediment supply.

Reading a Christmas-tree structure carefully allows us to reconstruct a surprisingly detailed history of basin evolution and salt mobility from a relatively compact volume of rock (it’s like a gift from nature).

- Exploration: From a subsurface perspective, Christmas-tree geometries are double-edged:

-

- They create a rich variety of traps and migration pathways. Branches can juxtapose reservoir and seal, and tiered minibasins often host stacked reservoir intervals.

- But they can also mislead: intrusive salt sheets may masquerade as younger stratiform evaporites, and complex velocity structures can distort seismic images. Misinterpreting the age or geometry of salt branches can propagate into errors in burial, maturation and migration histories.

Outcrop analogues, such as the Flinders Ranges (Dyson, 1999), and well-calibrated seismic studies (such as the NW German Basin) are therefore essential companions when exploring in salt basins where Christmas-tree structures are likely.

- Natural laboratories for salt rheology and geodynamics: Because they involve strong localisation and repeated reactivation, Christmas-tree systems are natural experiments in:

-

- The effective rheology of salt at different depths and contents.

- The interplay between internal overpressure within salt bodies and external tectonic forcing.

- The transition between intrusion, extrusion and welding over tens of millions of years.

High-resolution numerical and analogue models are increasingly able to reproduce zig-zag minibasin migration, tiered intrusions and complex weld networks. Comparing those models with real Christmas-tree examples helps calibrate both rheological laws and boundary conditions in a way that simpler, single-stage diapir models cannot (Peel et al., 2020).

A (geo)dynamic Christmas wish-list

As with real Christmas trees, part of the charm of salt Christmas trees is in the details: the small branches, the ornaments of minibasins and welds, the lights provided by careful seismic imaging. But behind the aesthetics lie quantitative questions that are very much alive in salt tectonics research:

-

- Can we turn the geometry of a Christmas-tree structure into constraints on time-dependent salt flux and sedimentation rates?

- How well can we date individual branches and welds to pin down the timing of reactivation events?

- Under what combinations of boundary conditions do numerical and analogue models spontaneously grow Christmas trees, rather than simple diapirs or walls?

Answering those questions will require work at the interface between field geology, seismic interpretation, stratigraphy, analogue and numerical modelling. It also requires good case studies: carefully mapped, well-dated examples where the tree rings of salt and sediment can be read in detail.

In the meantime, as the year winds down and you find yourself decorating an actual tree or enjoying holiday lights, spare a thought for the slower, deeper Christmas trees growing quietly in salt basins. Their ornaments are minibasins instead of baubles, their lights are reflection packages in seismic volumes, and their stories span tens of millions of years, but for geologists and salt lovers, they might be the most interesting Christmas trees of all.

But what about you: do you belief in Christmas(-tree strctures)? Have you ever found one in your seismic data? Are you team intrusive or extrusive salt wings?

I wish you a Christmas full of love, with your family and friends and a lot salty gifts (you can note that for me).

Merry Christmas and happy new year!

(and keep on keeping on!)

References Dyson, I. A. (1999). The Beltana Diapir: a salt-withdrawal minibasin in the northern Flinders Ranges, South Australia. MESA Journal, 15, 40–46. Grzybowski, Ł., & Krzywiec, P. (2019). Analysis of the evolution of the Goleniów salt diapir in the Mesozoic - Preliminary results. EuroAsian Mature Salt Basins. Krakow: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Geoscience Technology Workshop. Mohr, M, Kukla, P. A., Urai, J. L., Bresser, G., & Schoenherr, J. (2007). Subsurface seismic record of salt glaciers in an extensional intracontinental setting (Late Triassic NW Germany). Journal of Structural Geology, 29(9), 1301–1327. Jackson, M. P. A., & Hudec, M. R. (2017). Salt Tectonics: Principles and Practice. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139003988 Maystrenko, Yuriy & Scheck-Wenderoth, Magdalena & Bayer, Ulf. (2010). Major phases of salt tectonics within the Central European Basin System, EGU General Assembly 2010. Peel, F. J., Hudec, M. R., & Weijermars, R. (2020). Salt diapir downbuilding: fast analytical models of salt and sediment geometries. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 113, 104132. Varela, R., & Mohriak, W. U. (2013). Halokinetic rotating faults, salt intrusions and their seismic expression: implications for exploration. In: Tectonics and Sedimentation of South Atlantic Margin Basins (special volume). Butler, R. (2022, January 15). Dutch graben margin VSA. https://web.archive.org/web/20220125200809/https://www.seismicatlas.org/entity?id=026b91b3-c042-4f7b-802d-756a4613fa97