With love for geoscience comes a zest for exploring the natural world. What we want to explore might not always be close to us. But science finds a way, even if it means sailing to the middle of the ocean. This week, we are going to dive into the nuts and bolts of how research cruises work in this blog post by Kuan-Yu Lin from the University of Delaware. Kuan-Yu recently sailed as an igneous petrologist for the IODP Expedition 399 aboard the JOIDES Resolution which is set to retire next year.

Land and sea expeditions are foundational to Earth Sciences. Exploring the natural world has advanced our society to utilize natural resources and leave traces of human civilization even on the moon and beyond. Today, while Earth Scientists continue to deepen our understanding of the planet, research cruises and field expeditions have become very organized endeavors. Participating in a well-planned expedition can advance one’s scientific training, critical thinking, and teamwork skills. Most importantly, it’s fun – you get to travel to remote areas that withhold unanswered questions and be one of the few scientists to study the new specimens before anyone else. Today, I invite you to sail with me and delve into various aspects of scientific research cruises. Welcome aboard!

Kuan-Yu Lin is an igneous petrologist who studies peridotites from the seafloor to learn about plate tectonics.

How to attend a research expedition?

First, you need a properly equipped ship to do the proposed science, a group of staff and scientists, and funding to support it all. Typically, this is obtained by a few principal investigators (or PIs) submitting a proposal to a funding agency. If funded, ship time will be negotiated and one or two of the original PIs will sail as the chief scientist(s). It is at this stage that they will start assembling a science party that covers all the required expertise to meet the scientific objectives! It is common for scientists to reach out to their colleagues and recruit interested individuals to join. So, if you are a graduate student or postdoc, chances are that opportunities will come across if your PI has projects or active collaboration on sea-going science!

For larger projects like the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), there will be an open call to the scientific community to apply as a shipboard participant. You will likely have to submit a research proposal alongside your CV, and the operations staff and co-chief scientists will do their best to assemble an inclusive team.

Another intriguing way to attend is to work at an oceanographic institution as a marine specialist. In this case, you will be sailing routinely and providing vital scientific expertise. There is almost no limit on what your specific background can be as a wide range of specialties are needed, such as remote sensing, imaging, electrical engineering, and outreach and education, to name a few.

Life at sea

Sailing experience can differ drastically depending on the scientific objectives, the operations, and the personnel on each cruise. However, here’s a list of commonalities that I have observed (on US-based ships):

Seasickness

Some get very seasick, and some don’t – it depends on the weather, the ship size, and how your body reacts to motion. It’s a good idea to bring medication, and it will take a few tests to figure out your body’s preference. For me, a bonine a day keeps me functioning fine, but on a large ship like the JOIDES, less is needed. Scopolamine patches give me terrible side effects but work well for some people.

You will be doing (overtime) shifts

Unlike daylight-limited fieldwork, people on research cruises work around the clock in the form of shifts. During IODP Expedition 399, for example, personnel were on 12-hour shifts. My shift was 1 pm to 1 am. But as there was a crossover science meeting at 12:30 pm (which is wise to get food ahead of), I could not just sleep until 12:50 pm and then jump right onto my shift. It’s also hard to get off shifts on time as extra lab work, meetings, and discussions are often needed to cope with the unexpected. But when you do, then you can take a break either at the gym, movie room, library or on the deck if you have a starry night!

Learn your vocabularies

You might be surprised that there is no “bathroom”, “bed”, or “kitchen” on a research vessel. Well, they are there, but instead called “head”, “berth”, and “galley”. There are many other examples, to an extent that there is a dedicated maritime dictionary!

Collaboration and communication!

Now let’s finally get to “work”! Usually there will be a few days of transit before arriving on site, during which the science party will go through expected work and coordinate a workflow that make sense to everyone. Familiarize yourself with your tasks!

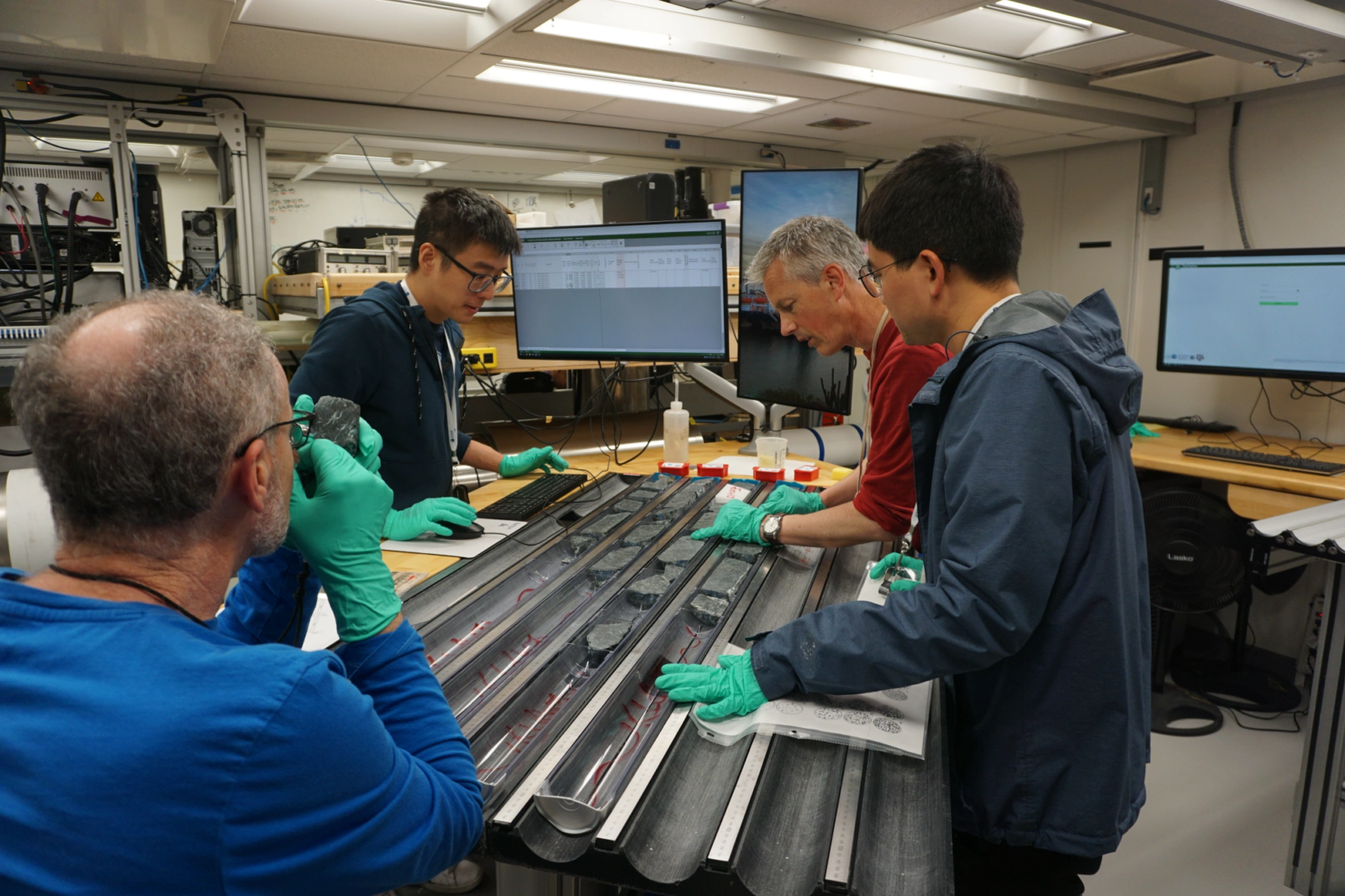

The IODP Expedition 399 igneous petrology team inspecting recovered drill cores at the description table aboard the JOIDES Resolution. From left to right: Mark Reagan (University of Iowa, USA), Kuan-Yu Lin (University of Delaware, USA), Johan Lissenberg (Cardiff University, UK), Haiyang Liu (Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China). Photo credit: Lesley Anderson and Sarah Treadwell.

Once arriving on site, the intense around the clock work begins. In our case, after “core on deck”, they get split, curated, and sent onto the description table for us to characterize their features. As igneous petrologists, we worked in groups of two where we would first determine the rock type (based on the primary minerals present), then estimate the relative size and proportions of each mineral, then characterize any additional features. On top of description work, we must compile everything into various reports, which involves endless thinking, discussing, plotting, and writing! But most importantly, we are there to do science, so we keep track of our research plans, how that changes with what we are recovering, and how to collaborate with others.

Post-cruise research

The cruise is just a brief phase of the project where most research is done afterwards. You will bring the collected samples back to the lab and make detailed analysis, share your discoveries with the group, and collaborate and publish the results ideally within a few years after the cruise, though some work can take longer! As an early career scientist, I now appreciate how beneficial these collaborations can be – the scientists that you sailed with can become your future postdoc advisors, mentors, or even letter writers!

Communication and outreach

Scientific research cruises are one of the few modern franchises that still encapsulate the spirit of exploration and fulfilling our natural curiosity. Since we are commonly supported by tax dollars, I believe it is important to effectively communicate what we discover to the broader community, and to think about ways of how our research can benefit the society as we go.

Thank you for joining me on this voyage, I hope to soon learn about your sailing experience too!

Michael Pons

Really nice blog Kuan-Yu Lin & Rajani, I’ve always wondered what it’s like to take part in an OIDP expedition, so thank you for sharing your experience with us !