In this weeks Wit & Wisdom, revisit some cybersecurity 101 nuggets!

We are not even half-way through 2021 and I can list more than a handful of occasions where my cyber-safety, both private and professional, was jeopardised (that I have been made aware of, the actual number is probably much higher). The Dutch research council was hacked1 (ransomware; documents leaked after refusal to pay; funding schedules pushed back by 5 weeks); a malicious email supposedly from the section head urged me to come by their office ASAP (very out of character); my personal data were stolen from my alma mater’s alumni database; my laptop was not automatically backing up all the brilliant work I was doing from my home-office because I did not realise I would need to connect to the institute’s network at a specific time to make the backups happen (facepalm); my personal data got hacked from the corona test centre (leading to a surge in spam emails and texts); and GitHub warned me that GitHub Actions very shortly contained a bug that allowed others to alter repository code. Colleagues got their encrypted passwords hacked2 and online conferences were interrupted by people shouting profanities. Ouch. Our work is not exempt from cybercrime. So what basic measures can we take to protect ourselves and our research?

Cybersecurity breaches by external parties require a ‘way in’, which can often easily be obtained through phishing or social engineering. Although companies can suffer from malicious users (e.g. employees that sell sensitive data or login credentials), well-meaning employees usually enable a breach by accident.

Take for example the ransomware attack that infected 269 servers of Maastricht University (UM) in the Netherlands on the 23rd of December, 2019. The report of the analysis by digital security company Fox-IT3 was published by UM afterwards, helping us to better understand how large-scale attacks work. It turned out that the whole attack affecting 1647 servers and 7307 workstations, threatening exams, salary payments, and research, started with one work laptop where someone clicked on a link in two emails in October! Downloading the Excel file linked to then activated an unsigned Macro that automatically downloaded malware from the web (see point 1).

Through this remote access malware (SDBBot), the hackers were able to explore the university’s network. In November, they found a server that was out-of-date (see point 2) and thus vulnerable to exploits (the Eternal Blue exploit in particular). This way, the hackers gained full access and could install other tools (e.g. Meterpreter, PowerSploit and Cobalt Strike). About a week before the final attack, the university’s anti-virus software picked up on the suspicious activity. PowerSploit was removed by the software, the use of Cobalt Strike logged, but no other action was taken due to the settings of the anti-virus program (see point 3). The attackers then simply turned off the anti-virus program (through the default domain administrator account) and finally, on December 23, they deployed Clop ransomware. This ransomware encrypted files with RSA 1024 keys randomly generated per file. UM employees could no longer reach their email, their files, nor their backups (see point 4). After a week of investigating, debating and communicating with the hackers, UM paid 30 bitcoin to have their files decrypted. The FOX-IT report was shared, the systems restored and a Security Operations Center founded to prevent future attacks.

Now obviously the IT department of your institute is responsible for taking the appropriate digital security measures, like restricting access, segmenting the infrastructure, keeping systems up-to-date and backing up vital data. However, from the UM example it is clear that each of us has a personal responsibility as well. Basic cybersecurity suggest the following4:

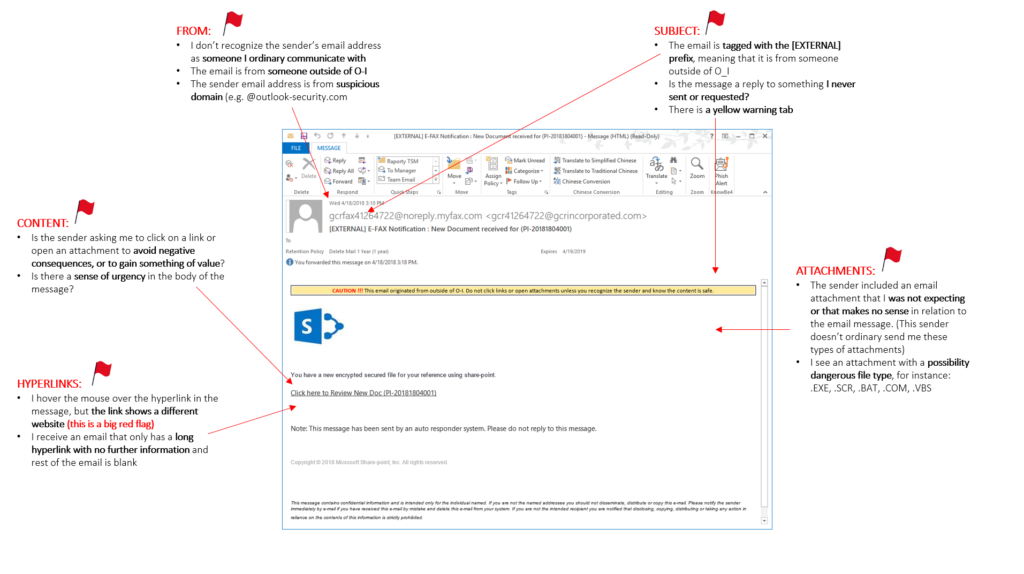

Red flags in an email. Dorotafreitag, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

(1) Be suspicious: do not open emails, attachments, or links that are unexpected or look fishy. If the business offer sounds too good to be true, or the sender asks for information they should not ask for (like a payment or a password – never ever give your password, not even to IT), it is fishy and it is phishing. If the email is not personally addressed to you, or the text is badly spelled, it is fishy. If you are asked to do something right away, like clicking a link, it is fishy. Check the sender’s email address, not just the name your email client shows you. Check URLs (hover over the link and wait to see the real address) and make sure they start with https, not http, and that the target address is correct (the part of the address before the first single slash and after the first dot before the extension, so egu.eu for this post). You can also check whether a website is safe by checking Google’s Safe Browsing site status. Use an email client that blocks external content and disable automatic calendar entries from invites. Report suspicious messages to the IT department.

(2) Keep your software up-to-date. Do not ignore those pop-up messages asking you to install, even though you just got everything to work with the current OS version (sigh). Updates can include fixes of exploits so they really are necessary. And similarly update your phone, tablet and other devices as well, especially if you use them for work.

(3) Use anti-virus software provided by your institute (even if you use a private machine, even if it is a Mac) and listen to it. Let it scan regularly automatically.

(4) Besides online backups, make sure you have offline backups as well, like on a USB stick or a hard drive. These offline backups will not be harmed during an attack, while online backups can.

Other important steps to take:

(5) Listen to your IT department. Take that short course on IT security they offer. Update software and set new passwords when they ask (without grumbling).

Lewis Ogden, CC BY 2.0

(6) Get creative with your passwords. Each account deserves a new password so that when one account is compromised, another is not necessarily in danger as well. To make life easier, use a password manager like KeePass, which can also generate strong passwords. Bonus: you will not need those annoying post-its underneath your keyboard any more! Use two-factor authentication when available (this 2FA will check upon login that it is really you by for example sending a text message with a code to a different device).

(7) Change the factory password of your home router and enable the firewall.

(8) When connecting via public Wi-Fi networks, use your institute’s VPN. Before travelling, think about what data need to be on your laptop and what sensitive or important data can stay home. Secure your laptop and other devices with a password and lock screens when they are not in use.

(9) Be mindful of what you post online, what is visible in videos and how bits of information can be pieced together to paint a bigger picture. Use communication software approved by the IT department and secure online meetings with a password only given to invitees.

(10) If you are a software developer, make yourself familiar with secure development lifecycles and strategies like secure and defensive programming5.

Now I am sure you have heard the majority of these guidelines before. I also think it is a safe bet to say you do not always follow them. I hope you will though!

References and further reading 1 NOS article on Dutch research council hack 2 Examples of universities and research institutes hacked: Parool article (in Dutch) on hack UvA and HvA, article on UK higher education hacks, Abcnews article on University of California hack, CSIS list of large cyber incidents. 3 FOX-IT report and UM's response, FOX-IT blog about the TA505 hackers' work flow, Cybercrimeinfo and Jorge's quest for knowledge blog about the UM hack. 4 cybereason article on employers on working from home, Norton article on working from home, GFZ Potsdam IT department. 5 Wikipedia article on computer security, PT security article on secure software development.