Floods are among the most devastating natural hazards, claiming lives and damaging infrastructure.

The question of how we can be prepared for these extreme events quickly reaches an almost philosophical level: First of all, what is an extreme event? Second, how can we know what the future will bring?

For the last century hydrologists have relied on statistical concepts, which are based on observed streamflow, to assess flood hazard but this approach opens many other questions: Do we believe that floods follow a statistical distribution? How long do we have to observe streamflow to make predictions into the future? And how do we deal with changing atmospheric conditions because of climate change?

From a mathematical standpoint we cannot perform sound extreme value statistics with little data and in a changing climate. That’s where creativity – and counterfactual scenarios – come in.

Counterfactual scenarios: Thinking of what COULD have happened

The smaller the catchment, the less likely that the position of the catchment coincided with an extreme rainfall event within our observational period. If an extreme flood hits this catchment, we are usually surprised and call this event unprecedented.

But again, this perception is only based on our short horizon of past experiences. If by now, you think that this way of assessing flood hazard is a rather strange way of doing it, be relieved because many hydrologists agree (see e.g. this paper).

We can be more creative instead of just waiting like sitting ducks for the next extreme flood to happen. Detailed observations of rainfall events, e.g. by weather radar, and powerful hydrological models enable us to simulate a large number of hypothetical events (counterfactuals) that did not happen in the past but might have happened.

Have you ever asked yourself how a rainfall event that caused a flood elsewhere would have affected your area? This idea is the basis of counterfactual thinking. The idea has been around for almost a century (see a good review here) but really picks up with nowadays computational possibilities.

A bridge destroyed by floods in the Himalayas. Find the person for scale. Image credit: Paul Voit.

In regard to flood risk management we are particularly interested in “downward counterfactuals”, scenarios with a worse outcome than they had in reality. With this pro-active approach we are able to broaden our data basis, find the range of extreme floods and adapt flood risk management accordingly.

For example, based on counterfactual studies we could show that the devastating flood that hit Western Germany in 2021 and was the costliest natural disaster in German history could have hit the region even worse, had the rainfall been slightly shifted. (By the way, one month before a similarly extreme rainfall event happened east of Berlin and had no impact, because the rain fell in a rather flat area with sandy soils and few inhabitants.)

And one does not need to look far, to find similar near-miss events that reflect the extreme 200-year design flood as we found in another study. In the USA, flood risk management is now moving towards the use of counterfactuals, rather than solely relying on extreme value statistics.

Leveraging counterfactual scenarios for science communication

Another advantage of the counterfactual approach is public communication.

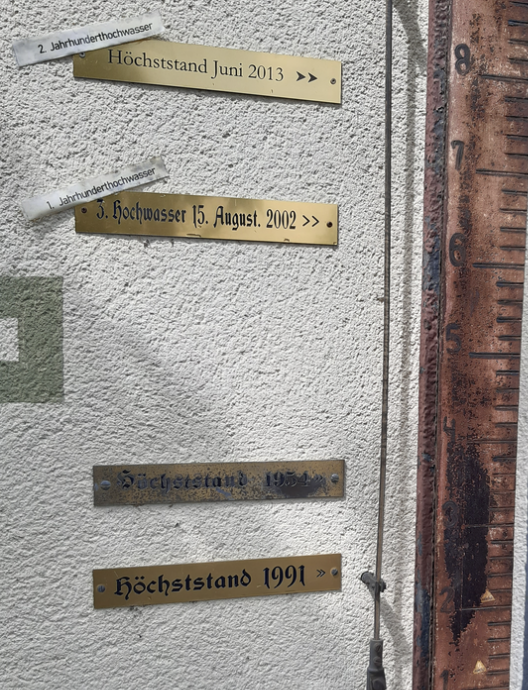

Currently, a lot of communication relies on statistical methods and the infamous “return periods”, which often cause confusion and mistrust. (“We already had a 100-year flood last year, why now another one? Your science is nonsense!”)

Two 100-year floods (Jahrhunderthochwasser) in 11 years, critically marked at a restaurant on the Danube close to Vienna. Image credit: Paul Voit.

In contrast, explaining to stakeholders that a recently observed rainfall event could have affected their interests or assets much more strongly, had it just happened in a slightly different position is much easier and leads to broader acceptance.

However, flood risk assessments based on counterfactuals will be only meaningful if the counterfactual scenarios are plausible. To which extent can rainfall events be shifted? What are realistic scenarios?

I think we are on the right track and these are the questions which we will have to tackle in future research projects to harness counterfactuals as scenarios for hydrological modelling and powerful public communication tools.

Keith Beven

But there is surely a problem with such an approach Paul. It is not enough to produce many potential projections of what might possible (which might include the “probable maximum flood” , but to decide how much money society is prepared to invest in mitigating the impacts of floods. A general rule of policy formulation is that is that the response should be proportionate to the risk. But risk assessment implies trying to assign some probabilities to scenarios (traditional flood distributions were only one pragmatic way of doing that, with statistics that do allow uncertainties in the estimates to be estimated even if that was rarely done). Now as soon as you move to counterfactual events or admit to potential nonstationarity (not only in the climate forcing but also in the assets at risk as in the USACE study), that becomes difficult of course. So we can have no secure estimates of risk, but still have decisions to make about investment (including the precautionary and most effective approach of not building on flood plain areas – something which even the very best analyses of hydrologists have clearly not prevented over the last decades). For every counterfactual event, including changes in land use as well as inputs, you can certainly estimate damages (with uncertainty) but how then to recommend a level of protection and, of course, the remaining residual risk when that will almost certainly not be protection against the largest event that could be envisaged. And since we are dealing with epistemic uncertainties there can be no right answer, only the consequence of making assumptions (assuming a stationary flood distribution is just one possibility). There are some ways of introducing epistemic uncertainties into a probabilistic risk analyses (e.g. Rougier, J and Beven, K J, 2013, Model limitations: the sources and implications of epistemic uncertainty, in Rougier J, Sparks, S and Hill, L (Eds), Risk and uncertainty assessment for natural hazards, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 40-63) but this would require some subjective assumptions about likelihood of counterfactual events. But if not that, how should society make decisions about how much to spend? I actually raised the same question in 2011 (I believe in climate change, but how precautionary should we need to be in planning for the future? in Hydrological Processes) but I am not sure there has really been much advance in thinking since. I suggested then, that since such spending is in competition with all other demands on budgets (health, eduction, transport ….), the amount of spend was likely to be decided first, the impact of the hydrologist might come in how best to distribute that spending. I think we can probably all agree that flood risk management and public communication need improving (including the important concept of residual risk rather than protection) – even if recent emphasis on the role of natural flood management in mitigation would seem to carry a danger of undermining confidence in the science even more. But the fundamental question remains, how best to decide on investing money in flood mitigation. Do counterfactual events for multiple communities at risk help more in that than (uncertain) flood risk distributions?

Pierluigi Claps

I find the discussion opened by this article and by the comment by Keith Beven very interesting.

I can contribute with an Italian perspective, related to the activities of the National Department of Civil Protection.

First, I believe that Keith Beven’s position is correct. It is very difficult to fit the work scheme of counterfactual analyses into a perspective of resource allocation for flood risk mitigation. However, the counterfactual approach is extremely useful for strengthening Civil Protection Planning actions, which include a crucial component of communication with the population.

The development of a city Civil Protection plan requires, first and foremost, communication between scientists and administrators, who must be convinced that certain events that have never been observed in their territory can actually occur. Presenting a simulation based on a counterfactual approach is extremely useful in this sense. It emphasizes the concept of perception (it has already happened 10 km away, so it can happen here too) rather than the concept of probability of exceedance: the latter is generally very unpalatable to mayors and municipal administrators, especially if it can’t be applied on spending funds on structural prevention.

On the contrary, the presentation to the administrators of a counterfactual flood scenario can be based on the transfer of historical information from another location, as codified e.g. in this paper https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-023-01300-5, and can be convincing in the assumption that it can happen also in their areas. The transposition of this flooding scenario into the Civil Protection Plan will determine subsequent non-structural prevention actions, fundamentally based on information and early warning of the population, which are crucial for saving lives. Summarizing, my two cents sounds like: probabilistic scenarios are certainly necessary for strategies for spending funds on structural interventions, while counterfactual scenarios are extremely useful for Civil Protection planning.