The sustainable and responsible use of mineral resources is a challenging task, yet essential for the benefit of our society. In this week’s blog, Dr. Νicholas Vafeas, an economic Geologist with a rich background in energy and mineral resources policy, shares his views on the urgent need to develop a holistic approach that can help integrate sustainable practises without posing any further risks to the planet Earth.

Dr. Nicholas Vafeas is an economic geologist with a rich background in energy and mineral resources policy. Originally from South Africa, he has worked on various commodities in many locations, from the world’s largest deposit of platinum group minerals, to 4 km underground in the depths of the deepest mine on the planet. His experiences range from engaging with remote communities in the Kalahari Desert about the impacts of mining to contributing to Irish Parliamentary publications on the role of geothermal energy. Nick’s passion lies in utilising raw materials to the betterment of global society. More of his work can be found on his official website.

I learned a new word the other day—solastalgia, the emotional distress when your home environment shifts in a negative way. We can all think of examples. It’s this kind of anxiety that fuels our drive for change, motivating us to demand better environmental policies, cleaner technologies, and a more sustainable future. But the paradox of our well-meaning intentions is becoming clearer: the very industries publicly blamed for environmental destruction are essential to its preservation.

Enter the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA). The EU is increasingly recognising the critical need for metals and minerals in powering the Green and Digital transition. The CRMA essentially says no EU country can rely on a single non-EU supplier for more than 65% of its strategic raw materials. Bear in mind that China alone currently supplies 100% of the EU’s processed rare earth elements. These elements are essential for manufacturing everything from electric vehicle batteries to wind turbines and solar panels, and are crucial for the EU’s twin Green and Digital transitions – This is key!

While policymakers seem to accept this, society at large often doesn’t. Over the past decade, climate protests have grown significantly, with societal movements calling for urgent action to mitigate climate change and environmental damage. These movements have played a crucial role in pressuring governments and corporations to adopt sustainable practices and move towards a greener future. Brittany, France, is a prime example. Imagine living just above France’s second-largest lithium deposit (BRGM, 2019), only 130 meters beneath your cosy home, sounds like a sci-fi plot, except it’s real, and it has made locals understandably nervous. Lithium, by the way, is essential for all the renewable tech and digital gadgets with which we occupy ourselves. And it’s not just Brittany. Protests against new mining projects have cropped up in Portugal (Bayley, 2023), Germany (Zimmermann, 2023), Sweden (Duxbury, 2023), and Spain (Tennant, 2023). Europe’s having a collective meltdown about mining in their own backyard.

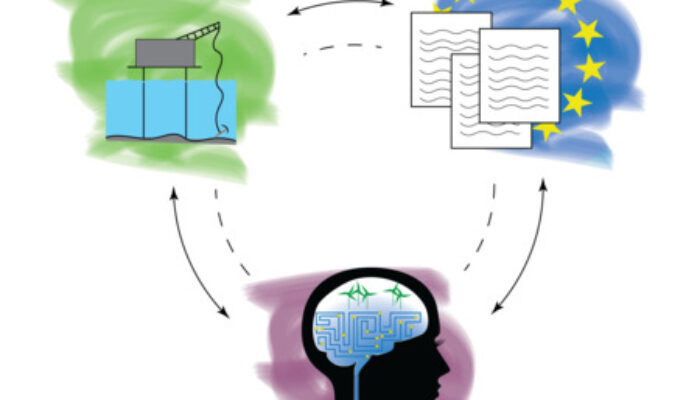

Elsewhere, the concept of using AI, an integral part of the Green and Digital transition, to combat climate change, is gaining positive traction (United Nations Climate Change 2023). The rise of applications such as ChatGPT, have made this a very tangible option that ordinary people can understand in a first-hand, practical way. It’s wild, and honestly, kind of magical! AI for predicting disasters, crop management, energy efficiency, and more. But here’s the thing, for AI infrastructure, you need copper and tonnes of it!

Which brings us back to mining. In a recent report from BHP (Jamasmie, 2023), it is estimated that the growth in AI technology will drive the demand for copper to 3.4 million tonnes per annum by 2050. With a global demand increase of 72% relative to 2021 levels. Take the largest copper mine in the world, Escondida, for example. An increase like this would be like adding the production of 3 to 4 Escondidas every year until 2050.

With limited domestic resources, attention has naturally turned to the ocean floor. While most of us would be familiar with this conversation, it wasn’t until recently that one country has actually taken the step necessary to carry this concept further. Norway, a non-EU country, is leading the charge in seabed exploration (Humpert, 2023). Free from EU regulations, Norway has the flexibility to pursue its own resource strategies. If, hypothetically, Norway’s extraction efforts prove successful (as historical resource policy trends suggest they might), it could very well position them as a key supplier of the critical raw materials the EU desperately needs. You can bet the EU would be quick to consider Norway a reliable source of these metals, given their limited options.

Of course, mining along the sea floor cannot go unchecked, and it doesn’t. The OSPAR Convention, an international treaty designed to protect the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic, is a model for how environmental governance can strike a balance between economic development and environmental conservation. OSPAR sets strict environmental standards to ensure marine biodiversity is safeguarded, pollution is minimised, and industrial activities, like seabed mining, are closely monitored.

In the face of increasing interest in seabed mining, OSPAR insists on comprehensive environmental assessments before any extraction begins. But the obvious question remains, with the limited understanding of the sea floor, how can we possibly truly understand the implications of mining in such a delicate ecosystem. And if we were to adopt the 30×30 approach (COP28, 2023), aiming to protect 30% of the planet’s land and sea by 2030, how can we determine which 30% of the seafloor to protect when we still don’t fully understand what needs protection?

This is the heart of the Great Green Paradox (and I wish I had a simple solution). The reality is that environmental initiatives like the OSPAR Convention are crucial for protecting our shared ecosystems, yet ironically, reaching our climate goals depends on green and digital technologies that, in turn, rely on mining. We need mining to protect the environment, even though mining itself poses risks to it. Complicating matters, let me ask you this, would you be okay with buying products linked to environmentally harmful practices? One only needs to point out that most (if not all) of the cobalt in the device you’re reading this on is sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As Europe looks to the future, it must confront the fact that the path to a cleaner, greener world isn’t as straightforward as we’d like. To succeed, we’ll need to strike a balance between resource extraction and environmental protection, a delicate dance that will require innovation, cooperation, and most importantly, a willingness to face our own uncomfortable truths.

References Bayley, C. (2023) Portugal's Barroso lithium mine project faces villagers' ire. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-67135047 (Accessed: 24 September 2024). BRGM (2019) Ressources françaises en lithium sous forme de roches dures. Available at: https://www.brgm.fr/fr/reference-projet-acheve/ressources-francaises-lithium-sous-forme-roches-dures (Accessed: 24 September 2024). COP28 (2023) The 30x30 Biodiversity Goal at COP28: Bridging Nature-Based Solutions and Climate Action. Available at: https://www.cop28.com/en/thought-leadership/The-30x30-Biodiversity-Goal-at-COP28 (Accessed: 24 September 2024). Duxbury, C. (2023) Sweden’s ground zero for EU’s strategic materials plan. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/swedish-ground-zero-for-eu-strategic-materials-plan/ (Accessed: 24 September 2024). Humpert, M. (2023) Norway takes next step to mine seabed minerals, dismaying environmental groups. High North News. Available at: https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/norway-takes-next-step-mine-seabed-minerals-dismay-environmental-groups (Accessed: 24 September 2024). Jamasmie, C. (2023) BHP warns AI boom would worsen copper shortage. Available at: https://www.mining.com/bhp-warns-ai-boom-would-worsen-copper-shortage/#:~:text=BHP%20(ASX%2C%20LON%2C%20NYSE,would%20boost%20global%20copper%20demand. (Accessed: 24 September 2024). Tennant, C. (2023) Lithium’s green potential fails to defuse Europe’s opposition to mining. Euronews. Available at: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/02/23/lithiums-green-potential-fails-to-defuse-europes-opposition-to-mining (Accessed: 24 September 2024). United Nations Climate Change (2023) AI for Climate Action: Technology Mechanism supports transformational climate solutions. Available at: https://unfccc.int/news/ai-for-climate-action-technology-mechanism-supports-transformational-climate-solutions (Accessed: 24 September 2024). Zimmermann, A. (2023) Tremor fears lay down hurdles for Germany’s lithium mining plans. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/germanys-lithium-extraction-earthquake-mining/ (Accessed: 24 September 2024).