Phoebe Sleath, a PhD student at the University of Aberdeen, guides us through the intersection of art and geology. She shares how she got into watercolour field sketching, how it became a valuable companion during her PhD journey, and how it serves as a powerful tool for communicating science

Why do you like doing geoscience? Throughout my undergrad degree, I would have said: because I like mountains and being outdoors. But after starting a PhD in COVID lock-down and facing a project I did not yet understand, I realised I did not know the answer to that question anymore. All around me it seemed like colleagues were suffering through the process just to reach the end, and I did not want that, I wanted to enjoy being in the process.

Post-PhD Geology and personal motivations

I started my PhD in September 2020 at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, UK with an initial title of “Thrust Fault Linkage through Rheological Multilayers”. Since university, I have loved being outside in the hills and I am a qualified Mountain Leader. I now enjoy hiking, rock climbing, swimming, and mountain biking. In my first year of undergrad at Durham University, I was very close to switching subjects. I was overwhelmed by the geochemistry and detail of classroom work.

Then we went on our first field trip to the Lake District, and I found that I inherently understood how the geology intersected the landscape through the map. Mapping became the best part of my degree. I did remote mapping in Greenland for my MscR with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), but I really missed being out in the field. It was quite clear from the beginning of my PhD that I wanted the project to be based on fieldwork and I wanted to go to different places. But that was quite tricky when I couldn’t leave my city due to lock-down restrictions!

Discovering painting

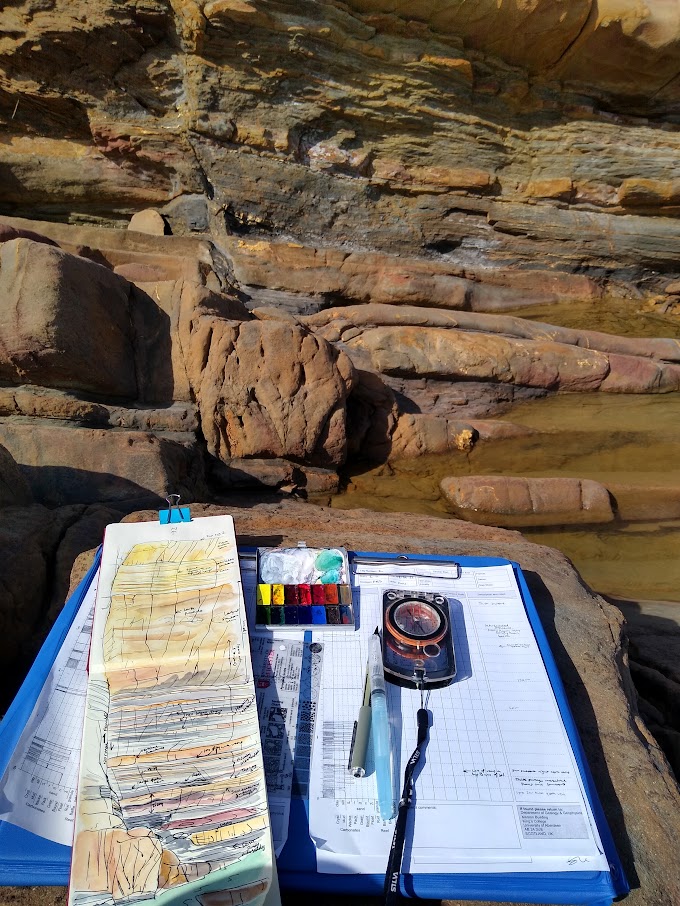

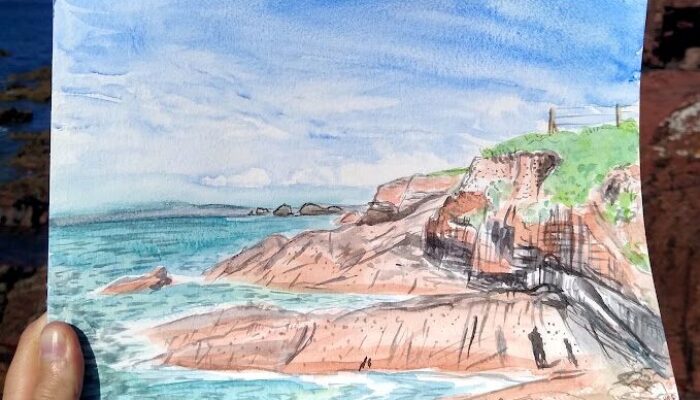

Finally allowed out on the field in September 2021, I took my watercolour paints with me as something to do while I was waiting for the tide to drop. At this point, science and art were quite separate for me: I occasionally painted in the evenings at home, and I had some mild success with mineral paintings that I’d quickly become uninspired by. I was studying a fold-thrust structure in the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, on the west coast of Wales in the UK.

It is beautiful. Bright red mudstones form sharp cliffs plunging down into turquoise water, swirling with sea spray, sea birds and seals. I painted the vibrant viridian sea and the deep cobalt sky, and then I moved to the rocks, thick paint for the Winsor red mudstones and diluted washes for the pale grey sandstones. As I was painting, wind blew the clouds away from the sun and the light changed, so I mixed red and blue for dark purple shadows bringing out the different faults and fractures. I realised that I was looking at the rocks in a different way, that painting was guiding my thoughts, was creating my scientific method. I felt a beautiful clarity and connection, in both looking at the landscape as a whole and the rocks and structure in its details. I was enjoying being in the process.

Intertwining sketching and fieldwork

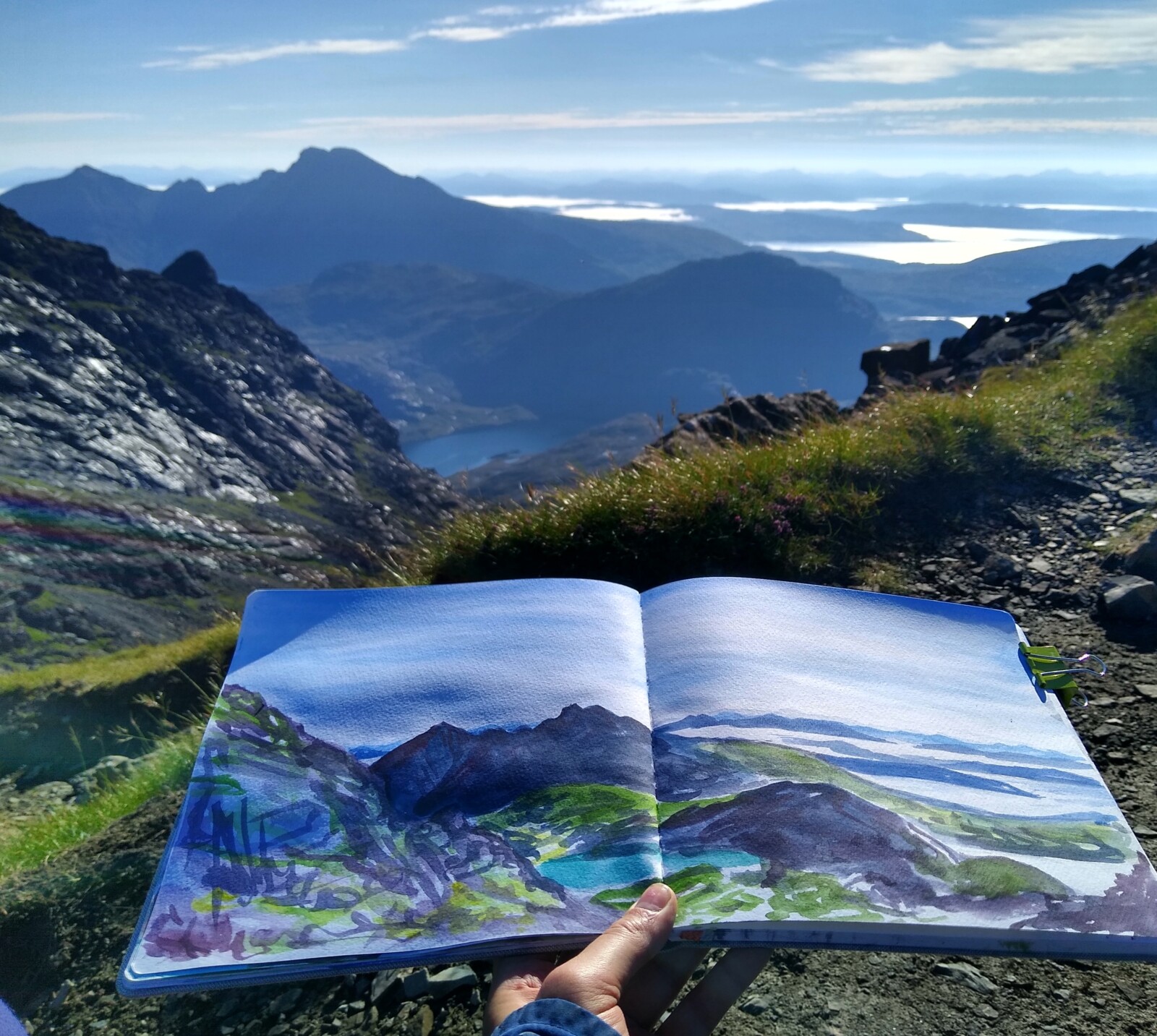

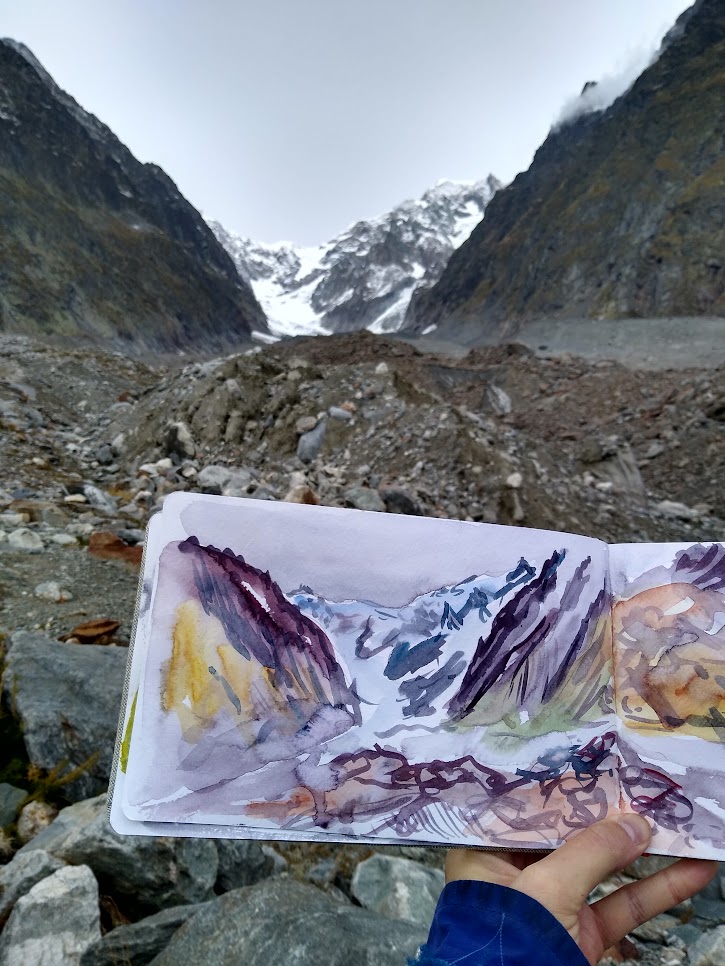

I began to take a sketchbook and paint palette with me everywhere. I found time on mountaineering club trips, at the climbing crag, on summit cairns, on fieldtrips, and on fieldwork! I saw lots of different rocks across Europe and painted them, granite and gneiss in Scotland, mudstones in Wales, volcanoclastics in England, conglomerates in Italy, turbidites in Spain, sandstones in France, limestones in Switzerland. Folds and fractures and faults and feelings.

Who came here before me? Did they look at the same things? How did they feel? I want to understand how other people think when they look at landscapes and rocks. Searching through archives, I noticed that before modern mainstream technology, scientists used creativity to study the landscapes and natural history of Scotland. Some of the biggest structural complexities and controversies were worked out with paper and paintbrush. Looking at the sketchbooks of the Geological Survey of Scotland team who mapped the North West Highlands, you can see plenty of beautiful watercolour landscape sketches, mixed with the more obvious geological concept sketches of faults and folds. Like Archibald Geikie, Henry Cadell, and Ben Peach, many of the survey geologists were competent amateur artists and writers. Hugh Miller is a famous Scottish geologist and writer who wrote beautifully about his explorations from fossil hunting as a child, to travelling through the beautiful landscape of Scotland to understand the geology. Art is not just pretty; it helps us work out our best ideas and allows us to share things we do not properly have the words for. The community has had to work over a long period of time, building on different people’s ideas and interpretations to reach a consensus.

Published and outreach work

In my first paper published earlier this year in the Journal of Structural Geology, we interpreted detailed stratigraphic relationships and thrust geometry at the Pembrokeshire outcrop to show that the thrust nucleated contrary to conventional models. Sketching helped me on fieldwork to complete a very detailed interpretation of the outcrop, to capture as much as possible and to help my mind to understand the complex deformation relationships of the rocks. The work agrees with and expands Eisenstadt and De Paor’s 1987 thrust fault model. It is interesting to consider how we choose outcrops and how we are influenced by conventional thinking.

I am currently in the process of finishing my second paper, which is an exciting exploration of the interpretation of large and complex fold-thrust outcrop in the Helvetic Alps in Switzerland by different researchers over time. I have compared over 100 years of interpretations of the outcrop, from 1916-2020, with digital geological mapping to assess the interpretation of structural geometry. We can see how they drew the shape and tightness of the folds, locate viewpoints they chose and consider how their viewpoint choice has influenced their work.

I am reaching the end of my PhD now, and my whole life has been changed by this process and my project. I really love the technical structural work I do, but I am so pleased to be able to view it through a creative and people focused lens. The best bit is how easily I can adapt it to other parts of geoscience like sedimentology and glaciology: I still have so many questions I want to answer! In my watercolour sketches I do not like to use scale bars or annotations, so they are easy to share with non-geoscientists. I share my work on social media and have presented at mountain festivals and exhibitions in Scotland. I am featured by the Scottish Mountaineering Press as one of their Creatives and I was lucky enough to be invited to talk about painting and Geology at the ‘Creatives Live’ event at the Fort William Mountain Festival in February this year. I think it’s important to share my work like this because the art-science interface shows how accessible science is and helps give such a sense of purpose to being creative and getting outside; something I have found so valuable for my mental health.

Recent sketch booking on the Sail Britain Artist’s Residency to the Small Isles, Scotland – views of Rum from Merlin (our sailing boat)!

Upcoming projects

Recently I am interested in making short films to share the process of painting and being in the landscape. I have won funding through the Geologist’s Association Curry Fund and the History of Geology Group to develop this. I spent a week sailing around the Small Isles on the West Coast of the UK on an Artist’s Residency with Sail Britain. It was so lovely to discover the island landscape and geology for the first time. Sailing is a really special way to travel and helped me to experience the area like the first geologists who visited. I am so excited to attend the Earth’s Canvas conference at the Geology Society in London in September to share my work!

What I hope you can take forward

So, why do you like doing geoscience? The best thing we can do is to find what we enjoy and do it more. The more we enjoy our work, the better we will get at it. To build a better world we need to allow science to be beautiful, diverse, and creative – just like scientists!