One of the earliest events of vEGU2021 was a debate on slow science organized by three early career scientists, with four invited speakers, Withney Behr, Valeria Cigala, Stuart Lane and Doerthe Tetzlaff.

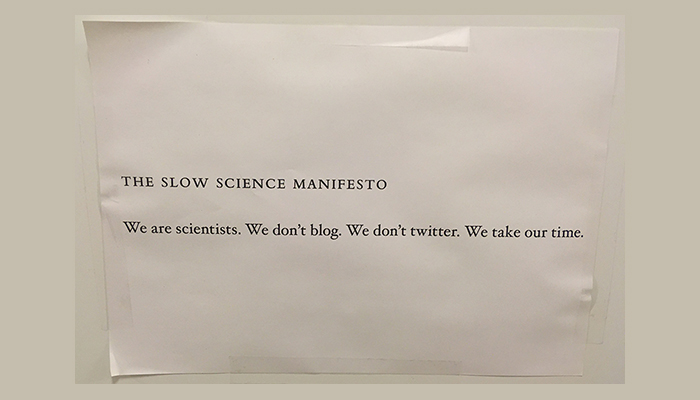

Before following this debate at vEGU21, I only knew the above door posting (on Stuart’s office door) and did not dig more into what is actually behind the movement – in my understanding it was simply related to the message of the slow food movement: pay more attention to what you eat, value it more and try to have a more sustainable diet.

But how does this actually translate into science?

The key idea behind slow science, as also iterated in this debate, is to sit back and try to spend more time on thinking rather than following the publish or perish maxim (see also http://slow-science.org/). The idea is to question ourselves whether our modus operandi is sustainable, and reflect upon the question: who do we actually publish for?

The debate evolved around a range of interesting aspects. One question that arose early on was if social media activity is necessarily contrary to the principles of slow science or whether it is rather an important aspect of modern science communication to the wider audience, an argument supported by Whitney Behr.

Doerthe Tetzlaff made the important statement that the principles of slow science should not lead to perfectionism, which might result in a quest to get ever “better” results rather than actually completing writing up and interpret one’s results.

This led over to a discussion around the role of papers for scientific progress: it was in fact argued that it is exactly because we force ourselves (or our students) to write papers that we invest energy and time into organizing our thoughts and synthesizing our ideas and results – which is indeed the most important aspect of our work.

A very timely question was brought up by Stuart Lane who asked if slow science is not an absurd concept in times of COVID. It was argued that society’s fast response to the pandemic was only possible thanks to the long lasting, steady progress that we made in the various research fields that contributed to face the pandemic.

One of the critical comments that was conveyed via the Q&A of the zoom session was the fact that slow science is today promoted by academics who are extremely productive in terms of papers (see also the detailed report by the organizers of the debate on the GM blog).

In my view, this critique partly represents a short-cut: senior, tenured academics are tenured because they were productive in the past; this does not mean that these academics cannot play a significant role to change the rules.

But obviously, changing the rules requires a big effort from all of us to overcome the number-counting attitude – in committees, scientific discussions and in the way how we present ourselves at conferences. The question of how to become a role model with this respect remains, however, extremely challenging.

Stephan Matthiesen

I followed the debate with great interest too, but two main points came to mind.

Firstly, similar debates have been held ever since I can remember since my student days over 20 years ago, with pretty much exactly the same points and arguments. I felt very much like in a time loop. It does seem like every generation of young scientist starts again from the same starting points. So the big question is why we are not moving forward in this debate, or what are the obstacles to change? This is not a criticism of anything that was said; everybody in the forum made good points, but it still feels unsatisfactory that we don’t seem to get beyond the stage of debates at a young scientists’ forum into actual science policies and the setup of academic institutions.

The second point is that the panel seem brilliant people with careers that look successful (although at an early stage). This is of course great, but for a panel discussion there is a risk of survivorship bias if only those people have a voice who have actually survived the system and are very successful. For future such debates it would be beneficial to identify people who left academia or did not manage to build up a successful career, even though many were quite as clever, dedicated and hard-working; many actually succeeded well outside academia, but their potential is lost to science. What can we learn from people who failed in the current system? Where are the obstacles, and what would they have needed to be successful too?

Again this is not a criticism of the debate or the panel, I just think that thinking about these two points would make a similar future debate even more fruitful.

Bettina Schaefli

Thanks for the feedback and for your thoughts. It would indeed be interesting to listen to those who did not succeed. I happened to almost be one of them. Three years in row, while I was already advanced in my career, I did not know in December whether I would still have job in the following March. I followed several hiring processes in engineering offices and the federal administration (where my expertise would not have been lost of course). My only strategy was “wait and see”. The reason that I finally succeeded was i) the Swiss research funding system (with several levels of personal grants throughout the stage of professorship) and ii) high ranked colleagues who managed to convince the human resources to continue to hire me despite of not fitting the classical career scheme. Both are critical players, both need to be continuously adapted to the need of modern academia.