The Early career representatives of EGU’s Geomorphology Division (Andrea Madella (University of Tübingen), Annegret Larsen (Wageningen University), and Michael Dietze (GFZ – German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam)) organized the ECS-Great Debate on “Slow science versus fast science” at this year’s vEGU21 – edited by Sabine Kraushaar.

– GM Guest bloggers: Annegret Larsen (Wageningen University), Andrea Madella (University of Tübingen), Michael Dietze (GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam) –

Geoscientists feel the pressure that the scientific system asserts on today’s scientists. During the past years it appears that voices critical of the status quo in the geoscience academic community have become louder. Organising an ECS Great Debate on the topic of ‘slow versus fast science’ at vEGU21 was a chance to check how accurate this impression was. The number of participants and questions in the Q&A chat far exceeded our expectations (500 participants). The GM ECS representatives invited a mix of young and more senior scientists to debate this topic, whom we all owe a great thanks. We summarize the topics of the discussion below and add some thoughts from the authors of this blog post.

Science communication and slow/fast science?

The slow science manifesto states ‘We are scientists. We don’t blog. We don’t twitter. We take our time.’, but is there a dichotomy between slow science and science communication? If so, where does it come from? Communicating the outcome of our science is important to all of us. Besides scientific publications and conference presentations, which are the main communication outlets (to scientists) communication to the wider public has become an increasingly expected demand on scientists. Because of the structure of social media, this can often be reduced to using Twitter or Facebook, but a more targeted communication to interested/concerned lay groups should not be forgotten, especially for policy makers. The forum for the latter communication type are often organised events, this communication is normally well prepared, and also targeted towards the audience. In contrast, Twitter and Facebook host ‘fast’ communication – and also very short, bearing the risk of oversimplification of the scientific outcomes. There, the targeted audience is potentially large, but it remains unclear who receives the posted information, which is likely to be an underlying democratic issue, and needs addressing. There is also a possible feedback-mechanism to investigate – namely, are we as scientists influenced by the ‘likes’ that some topics create, and thus more likely to pursue the most liked research? Whatever the case, it seems that the largest problem is that science communication is increasingly demanded from scientists. This poses a fundamental issue, because the main output of our research are scientific publications, rather than blogposts or Twitter feeds. Hence this demand of outreach activity is cutting into our academic freedom, as it demands to invest the most precious resource scientists have (and what the slow science manifesto is all about): time.

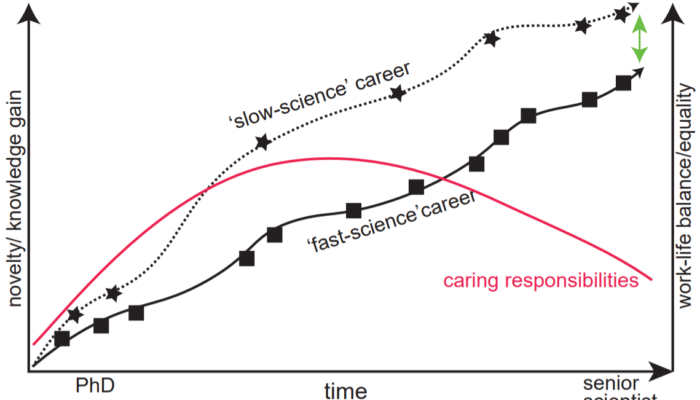

The slow science manifesto calls for less time pressure, not for slower scientific progress

The slow science manifesto explicitly calls for more time to think. However, the current system promotes the opposite: All career stages experience time as being the scarcest resource, while maintaining a healthy work-life balance is perceived as increasingly difficult. In the early career stages time is structured by short term contracts (a major issue according to both audience and panelists), which often does not allow to develop ideas and go into depth. The increasing number of PhD students, but constant low number of tenured scientific positions causes increasing competition, with h-index and journal impact factors still being widely used as metrics for the selection of candidates. In contrast, the increasing number of publications and their improved accessibility asks for investing more time in order to be able to dive into a topic. In particular, interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition takes the longest. Traditionally, the PhD degree consists in learning how to be a scientist, although taking time to dive deeply into a topic is not the target of this degree anymore. Instead, the target has commonly become the ability to quickly publish a predefined number of articles (commonly 3 papers per PhD candidate). On the other hand, scientific writing is a fundamental soft skill to learn thought- and argument-structuring. Scientific writing also makes authors acknowledge the inherent incompleteness of scientific work and favor productivity over perfectionism. We definitely need to share knowledge in order to move science forward, which is at the core of the job description ‘scientist’.

Publish-or-perish culture at the heart of the problem

The least publishable unit has been the norm for a long time. This has led to the current “fast science” paradigm, which finds the peer-review system near a collapse due to publications and journals in exponential growth. Following Lane (2017), this is equivalent to an economic overproduction crisis. All panelists in this Great Debate agreed that the system as present is unsustainable. The slow science manifesto is deliberately stating that it is not against the accelerated science of the 21st century. Slow does not imply no progress, it means that scientists are allowed to be unproductive when they’re busy collecting data, thinking, reading, and also failing. The benefits and problems associated with the publish or perish culture was heavily discussed during the Great Debate by the panelists as well as in the chat. As noted above, the positive aspects of publication pressure is that it forces scientists to reduce (to some extent) perfectionism, and helps the writer clarify the thoughts within the writing process. Also, scientists should be free to publish smaller, intermediate steps on their way of reaching a larger goal. On the other hand, many research institutions acknowledge that quality is more important than quantity and limit the number of papers listed in grant proposals or job interviews. For instance, the San Francisco Research Assessment (DORA) calls for abandoning citation indices for evaluation of researchers and their work. It is therefore evident that the problem does not lie in the number of publications per se, but rather in the attribution of merit on the sole base of publication metrics.

Slow science and the Covid-19 crisis

Is it timely, though, to call for ‘slow’ science while the Covid-19 crisis has shown us how important seemingly fast science can be (e.g. in developing vaccines)? It could be argued, that the development of the mRNA vaccination technique is in fact a slow science story (within a fast science system). A key scientist for the development of mRNA vaccines (Dr. Katalin Karikó) worked relentlessly for 40 years on the technique. Most of her work was done at PennState University, where she got demoted from her tenure track because she failed to acquire external funding. It was a continuous fight to keep her groundbreaking work going, and only possible through her enormous perseverance and the support of fellow colleagues. PennState still holds the patent to the technique, Dr Katalin Karikó however has never gained tenure and has left the academic system.

Ways forward

In summary of this Great Debate, we can agree that however we call it, a systematic change is needed and overdue. It is also clear that slow science does not mean to be slower, but to take time, which is expected to yield a greater knowledge gain in the long run. One important step towards slow(er) science is to increase quality and decrease quantity – a trend observed in many areas of life world-wide. Many of the more senior scientists have scientifically grown up within a publish-or-perish system, and it needs institutions to change rules to provoke the change towards more sustainability. The abandonment of indices to evaluate research(ers) seems common sense – but is it already widespread practice? Using the effective scientific age instead of life age to evaluate CVs of scientists would be a very important step toward a more flexible system, where researchers may take detours (like a braided river – however, does water not always search for the most efficient way?). Science could be more like a highway: you can choose your lane, you can leave, take a break, and drive back onto it to continue your journey. To us, it remains unclear how this relates to the mentioned ‘well-rounded CV’, an item that like many others in this Great Debate has only been touched upon. Maybe, before reconvening at EGU22, we should all take our time to think about it?

Annegret, Andrea and Micha

– GM Guest bloggers: Annegret Larsen (Wageningen University), Andrea Madella (University of Tübingen), Michael Dietze (GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam) –

If you want to know more about slow science:

The slow science manifesto:

SLOW-SCIENCE.org — Bear with us, while we think. (slow-science.org)

Further reading:

Lane, S.N. (2017), Slow science, the geographical expedition, and Critical Physical Geography. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien, 61: 84-101. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.wur.nl/10.1111/cag.12329

Stengers, Isabelle and Stephen Muecke (2018), Another Science is possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Oxford: Wiley, p 220.