The story so far, and how it developed

We left you in part 1 of our blog (Hydrological Sciences | Co-creating water knowledge (Part 1): The history and future of an interdisciplinary working group) two days ago, anticipating what we are doing and how you can get involved with us.

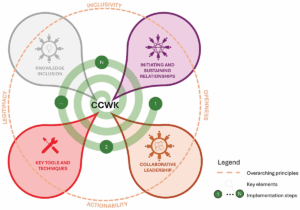

The IAHS Working Group on “Co-creating Water Knowledge” developed a “baseline paper”, defining core co-creation concepts. Continuing our work as an interdisciplinary group, we tried to define some key principles for co-creation. We identified four of them, as follows:

- Inclusivity: ensuring that all willing actors involved or affected are represented, acknowledged, and benefit from the co-creation process equitably while emphasising mutual respect and diverse ways of knowing. Our inclusivity principle aims to overcome power imbalances.

- Openness: fostering an open, trustworthy, transparent, respectful, encouraging, and creative atmosphere that is receptive to a range of practices of knowing and thinking, from modelling to sensing or feeling. This principle should not be interpreted as a call to open communication of protected knowledge systems (for example, protected indigenous knowledge) at any cost, but rather as a reflection on how to valorise and respect all forms of communication and non-communication.

- Legitimacy: ensuring fair representation and equal involvement of local communities, marginalised groups, or other non-academic actors as equal participants throughout the co-creation process and collaboratively defining research aims, questions, methodologies, solutions and decision-making accordingly.

- Actionability: using appropriate technologies and tools, including models, terminologies, symbologies and multi-functional approaches, that enhance water science in a way that is usable, useful, and used. This might entail the creation of socio-ecohydrological observatories to ensure long-term measurement of key meaningful variables that are relevant, accessible, and usable by the entire community.

Besides this, our paper highlights four key elements for co-creation: Initiating and sustaining relationships; Collaborative leadership; Key tools and techniques; and Knowledge inclusion.

Overview of Co-Creation of Water Knowledge (CCWK), guided by principles of openness, legitimacy, inclusivity, and actionability (orange dashed line), evolving through an iterative implementation spiral (green), and anchored by four cornerstone elements: relationships (purple), collaborative leadership (orange), tools & techniques (red), and knowledge inclusion (grey)

Finally, we tried to highlight the main challenges and opportunities related to co-creation, framing the research and policy areas that we’d like to tackle in the future. First of all, funding options should be restructured, to allow longer and more meaningful co-creation efforts.

Power dynamics should also be better, and more explicitly addressed in co-creation projects, especially when they are underlying injustice, marginalization of communities, colonial dynamics and extractivism. We need also to find a way to operationalize co-creation within standard hydrological practices, and institutionalize it in water-related policies. But, probably most importantly, we will need to overcome epistemic injustices which are still very present in water sciences.

Despite many efforts, water science, policy, and practice remains dominated by top-down, western scientific traditions, and in many contexts is still determined by (post)colonial hierarchies. This dominance, often referred to as epistemic hegemony or prejudice, marginalizes individual and community knowledge, leads to cognitive or epistemic injustice, and importantly misses opportunities for more effective, equitable, and sustainable water management.

Even in spaces and opportunities created for co-creation, groups that face epistemic injustice can be regarded as ignorant (e.g., of scientific or research project management norms) and not trusted to contribute or lead. Their contributions are often treated with suspicion, ignored, or regarded as less valuable or valid than those of social actors who belong to the hegemonic knowledge tradition. This stands as a barrier to effective and equitable co-creation and while a resultant exercise may be labelled as co-creation, outcomes lack diversity of knowledge and are only a reflection of the contributions of some participants.

Our perspective paper that can be found at: Castelli, G., Howard, B. C., Adyel, T. M., AghaKouchak, A., Agramont, A., Aksoy, H., … Ceperley, N. (2025). Co-creating water knowledge: a community perspective. Hydrological Sciences Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2025.2571065

The way forward

We aim to write a sequel to this paper towards the end of the decade, in which we provide more definitive and detailed instruction on cocreating water knowledge. In the meantime we will develop platforms to connect, inspire, and systematically document case studies covering all kinds of context, places, and challenges. The group is active and everyone is welcome to join.

Anahí Ocampo-Melgar presenting in Florianópolis, Brazil, in 2024

Side Event on Co-creation at the Scientific Assembly of IAHS in Roorkee, India, 2025

We are actively presenting our vision at different international conferences, mobilizing our group members in different continents, and we will be at EGU26. We highly encourage you to join and contribute to the The following sessions: is open for contributions:

Co-creation in Hydrology and Water Resources Management

Co-organized by EOS1, co-sponsored by IAHS

https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU26/session/57028

We are also organizing a Short Course this year, sharing our visions, experiences and ideas:

Co-creation in Practice: Challenges, Successes, and Strategies in Water Research

Co-organized by EOS2