Picture this: you’re hiking through a dry landscape when suddenly you hear it—the serene sound of a babbling brook. You round a corner and discover a small waterfall cascading into crystal-clear pools, surrounded by lush green ferns and wildflowers attracting buzzing bees. It feels like stumbling upon a secret oasis.

These magical streams that appear and disappear with the seasons are called intermittent streams, and they’re more important than you might think.

Why Intermittent Streams Matter

Intermittent streams—waterways that flow for only part of the year—are integral to ecosystems and our water supply. However, they are vulnerable to climate change, mining, and urban development. Making matters worse, as of 2023, these streams lost federal protection under the Clean Water Act in the United States.

Intermittent streams are difficult to monitor, so it’s important to find cost-effective approaches to understand the impacts and effectiveness of water management efforts. Scientists are getting creative with a surprisingly simple solution: cameras. Platforms like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Flow Photo Explorer and CrowdWater have collected thousands of photos of streams over time. But sorting through hundreds of thousands of images by hand? That would take forever.

This is where machine learning—essentially training computers to identify patterns from data—comes in.

Teaching Computers to “See” Water

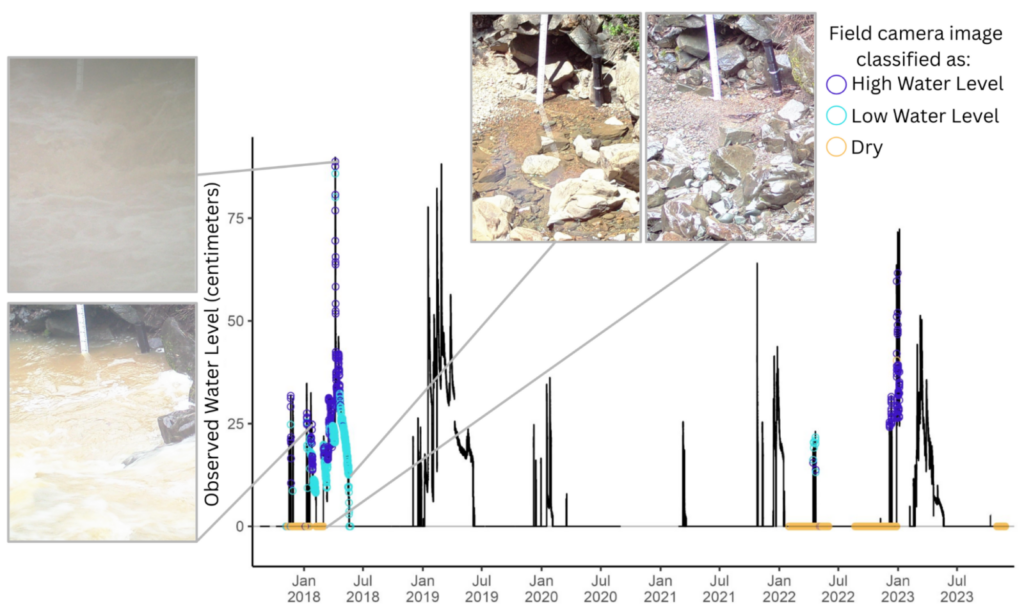

In a recent study with co-authors Garrett McGurk, Anahita Jensen, F. Martin Ralph, and Morgan C. Levy, we used machine learning to classify photos of an intermittent stream as dry, low water level, or high water level. Specifically, our study site was on Perry Creek in northern California, United States, and contains a streamgage and field camera operated by the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E). The figure below shows the image classifications compared to stream level observations at our study site, and they agreed remarkably well.

Observations of stream level and concurrent image classifications from field camera photos at Perry Creek from August 2017 – November 2023. Four example field camera images are shown. Field camera images were not available from 2019-2021.

We discuss how field cameras and the classification of field camera imagery, combined with weather and soil moisture observations, provide detailed hydrologic information important for understanding how climate affects intermittent streams. Because this image classification approach is transferable to other intermittent stream sites equipped only with field cameras, the methodology provides a low-cost option for observing relative water levels on sparsely-measured intermittent streams that can help water managers. To demonstrate this transferability, we tested our approach on two additional stream sites from the USGS Flow Photo Explorer, where it performed well at both locations.

What’s Next?

We hope that our method for classifying water presence on intermittent streams can be integrated into similar approaches like those in the USGS Flow Photo Explorer. This would support the broader effort to develop a low-cost, large-scale observation network for intermittent streams.

For Practitioners: If you’re setting up field camera sites, we recommend placing cameras along streams critical for water management objectives (like fish passage or drought planning), installing cameras at stable locations with clear streambed views, maintaining consistent camera types and viewing angles, and budgeting for long-term maintenance. The code and workflow for image classifications is available here.

Edited by B. Schaefli

A note from the editorial team: This is a guest blogger contribution received following a recent innovation in the Copernicus Publishing System: upon acceptance of your paper in one of our journals, authors are invited to consider turning their science paper into a blog post.