GeoLchat: A Bilingual Science Communication Experiment of Three Colombian Geoscientists

Una de las cosas más importantes que se les enseña en la academia a los estudiantes de ciencia alrededor del mundo es aprender a usar el lenguaje científico. Sin embargo, nunca se les enseña a hablar acerca de ciencia en un lenguaje sencillo, y tampoco a comunicar y divulgar sus investigaciones en lenguajes diferentes al estándar en la ciencia: el inglés. Esto dificulta los esfuerzos por hacer la ciencia más diversa, equitativa e incluyente. La mayoría de las universidades en Estados Unidos y Latinoamérica no tienen un enfoque en la comunicación y divulgación de la ciencia en sus programas (no a menos que el estudiante esté interesado en el periodismo científico o una carrera en comunicación). De hecho, es común que en la comunidad científica se les considere como habilidades blandas, lo cual a su vez, las hace poco atractivas para algunos estudiantes de ciencia. Esta semana las estudiantes de doctorado Carolina Ortiz-Guerrero, Lina C. Pérez-Angel de la Universidad de la Florida y la Universidad de Colorado-Boulder y la geocientífica Daniela Muñoz-Granados actualmente trabajando en el Servicio Geológico Colombiano, nos muestran cómo ellas están divulgando las Ciencias de la Tierra a la comunidad Latinoamericana.

One of the most important things science students around the world learn in academia is how to use scientific language, but they are never taught how to talk about science in simple terms, do outreach, or communicate their research in languages different from the standard for science – English. This impacts the way we promote science to be Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive (DEI). Most United States and Latin American based universities do not include training in science communication in their programs (unless you are in a science-journalism or communication track). Actually, the science community generally considers science communication and outreach as optional ‘soft-skills’, which makes them unappealing to learn for some science students. This week, two PhD students Carolina Ortiz-Guerrero and Lina C. Pérez-Angel from the University of Florida and University of Colorado Boulder; and geoscientist working at the Servicio Geológico Colombiano (Colombian Geological Survey), Daniela Muñoz-Granados show us how they’re bringing their science to the wider LatinX community.

Figure 1: La Pola Geologica showcasing the team members with their guest, paleontologist Isaac Magallanes, doing mineral #CosplayForScience. Follow GeoLchat on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook!

Así como el idioma, la ciencia hace parte de las actividades sociales y culturales en el mundo, y el idioma utilizado para comunicar y divulgar efectivamente las ideas científicas – por fuera del ámbito formal de educación- es relevante ya que afecta la percepción que la sociedad tiene de esta (Márquez and Porras, 2020). Por ello, los científicos que buscan el éxito en la comunicación y divulgación científica pero no son angloparlantes tienen un reto adicional: el comunicar investigaciones científicas – las cuales son usualmente producidas en inglés – en otros idiomas (Ramírez-Castañeda, 2020).

Just like language, science is also part of all cultures around the world, so the language science uses to communicate matters and has an effect on the public’s perception of science (Márquez and Porras, 2020). Therefore, scientists who are non-native-English speakers and want to succeed in scientific communication have an additional challenge: communicating scientific research – usually made in English – in other languages (Ramírez-Castañeda, 2020).

En regiones como Latinoamérica, la ciencia, su comunicación y divulgación atraviezan una crisis. En esta región el presupuesto destinado para ciencia, tecnología, ingeniería y matemáticas (STEM, por sus siglas en inglés), es mínimo comparado con regiones de países industrializados (RICYT, 2020; Ciocca & Delgado, 2017). También, el apoyo económico hacia profesionales de las áreas STEM también es bajo respecto a cupos laborales, lo cual lleva a muchos científicos a irse de sus países debido a la falta de recursos y oportunidades (Michelsen, 2022). Adicionalmente, en Latinoamerica los recursos públicos no apoyan significativamente las -pocas- propuestas de comunicación y divulgación científica en Español por fuera de la educación formal, y de hecho la mayoría de éstas iniciativas son financiadas de manera privada o por el público (crowd-funded). Esto hace que en esta región, en donde el nivel de inglés se correlaciona con el status socio-económico, no haya acceso igualitario ni a la ciencia ni a la comunicación y divulgación científica (Márquez and Porras, 2020).

In regions like Latin America, science, science communication and outreach are going through a crisis. In this region, the budget allocated to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is significantly lower compared to regions with industrialized countries (RICYT, 2020; Ciocca & Delgado, 2017). Also, the economic support to STEM professionals is low, as well as the job opportunities, which drives many PhD science professionals to leave their countries (Michelsen, 2022). Additionally, in this region, the local Spanish-speaking communication and outreach efforts are not a substantial part of a public budget. Instead, the few existing projects, are mostly privately funded (or even crowd-funded). Because of these and many other reasons, in Latin America – a region where the English proficiency correlates with the socio-economic status of the individuals – there is no equal access to science, and science communication outreach initiatives (Márquez and Porras, 2020).

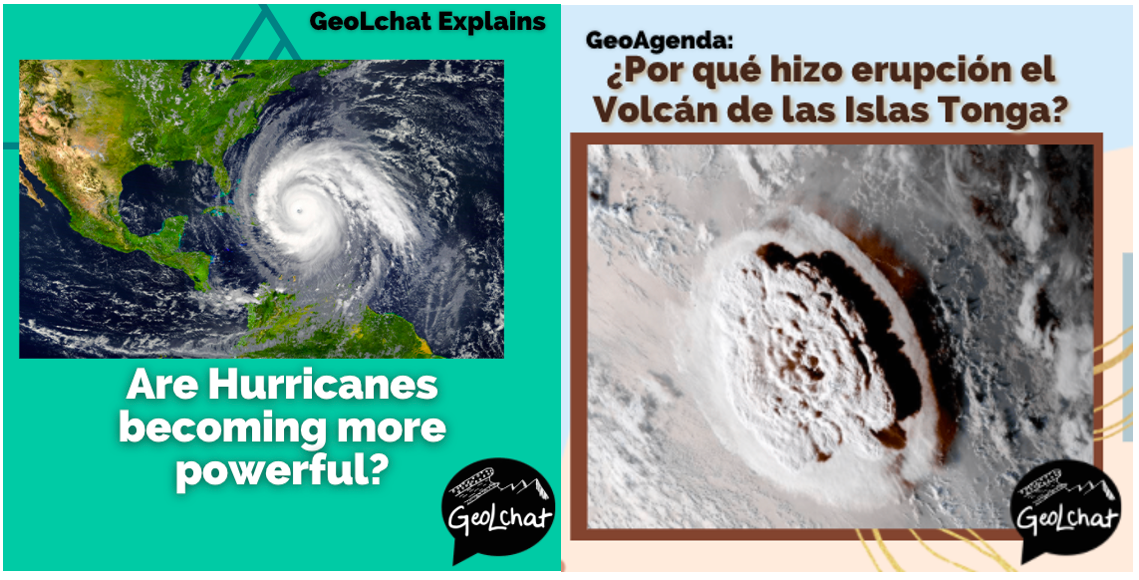

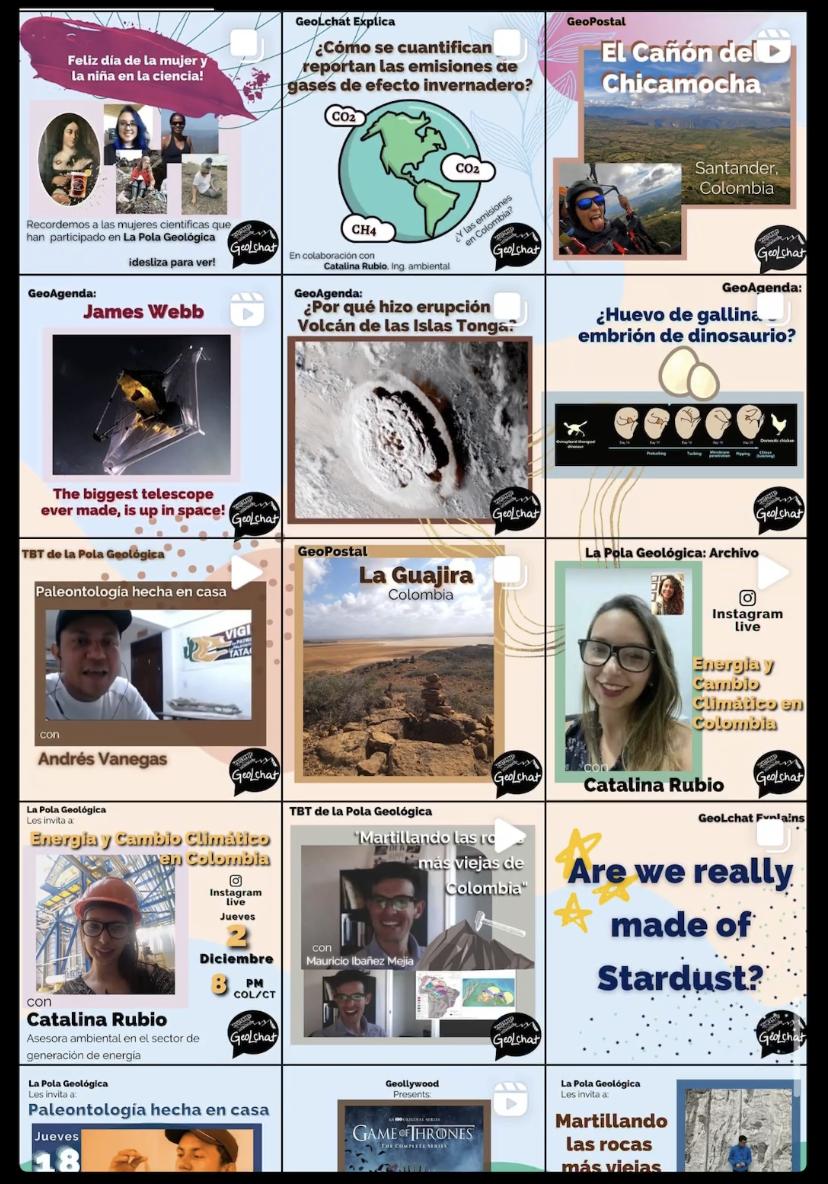

Como tres científicas Latinoaméricanas trabajando en ciencias de la tierra, planetarias y atmosféricas; hemos decidido tomar el reto de la divulgación científica utilizando dos herramientas sencillas que tenemos a la mano: nuestros celulares y redes sociales. Desde julio del 2020, hemos hecho un esfuerzo por traducir y comunicar los datos más interesantes y últimas investigaciones en nuestra área de la ciencia para el público general tanto en inglés como en español. Nuestro experimento se llama GeoLchat y a través de este queremos reafirmar que la ciencia debería ser comunicada en todos los lenguajes por su importancia en los aspectos públicos de la sociedad y para garantizar que sea diversa, equitativa e incluyente.

As three Latin American female scientists working on Earth, Planetary, and Atmospheric sciences, we have decided to approach the challenge of communicating science, using accessible tools that most of us have to communicate science: our mobile phones and social media apps. Since July 2020, we have pursued the task of translating and communicating the most interesting fact and novel research in our field to the general public, both in English and Spanish. Our experiment is called GeoLchat, and through this platform we are claiming science should be communicated in every language to emphasize its public aspect and its public commitment to DEI.

GeoLchat empezó en el 2014, cuando dos de nosotras íbamos conversando en un bus después de un largo día de trabajo de campo, mientras compartíamos fotos de rocas y paisajes en nuestras viejas cámaras y celulares. Como dos Millennials -muy activas en redes sociales-, creamos una cuenta de Instagram para darle a nuestros amigos y familia un pincelazo de nuestro mundo científico y de la belleza de los lugares a los que íbamos a aprender de geología. Pero no fue sino hasta el comienzo de la pandemia del COVID-19, en marzo del 2020, que GeoLchat nació. En ese momento, empezamos a filosofar acerca de por qué habíamos perseguido una carrera científica, y qué nos motivó a hacer un posgrado en Estados Unidos, y conversamos acerca de como mantener nuestra salud mental siendo dosestudiantes de doctorado. Una tercera colega se unió a nuestro proyecto, y desde ese momento hemos estado trabajando para construir una plataforma bilingüe para comunicar temas de ciencias de la Tierra, atmosféricas y planetarias para un público no científico. Para esto hemos tenido qué intentar, experimentar, fallar, preguntar e investigar. Pero sobretodo hemos tenido que pasar horas tratando de responder la siguiente pregunta: ¿Por qué a la gente debería importarle las ciencias de la tierra?

GeoLchat started back in 2014, during a bus-ride conversation after a long day doing geology fieldwork, when two of us shared rock-pics taken in our old-school cameras and mobile phones. As two – very active on social media – millennials, we created an Instagram account for giving our family and friends a sneak peek into our geology world and the beauty of the places we were going to learn about science. But it wasn’t until the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in March 2020 that GeoLchat was born. Back then, we started revisiting why we became scientists, what motivated us to be in the US pursuing grad school, and how we could boost our mental-health as two anxious PhD students. A third geoscientist joined our project, and since then we have been working towards building an organized bilingual platform for communicating topics on Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, for a non-scientific public. How? Trying, failing, asking, recycling, googling, and spending hours trying to answer this question: why should people care about Earth science?

Cuándo surgió el proyecto de GeoLchat, un proyecto en redes sociales con enfoque en comunicar/divulgar investigaciones geocientíficas en español, no existía. Nuestra falta de entrenamiento profesional en comunicación y divulgación científica hacia un público científico y no científico, ha sido un reto y un constante aprendizaje. Hemos desarrollado nuestro proyecto basadas en aplicaciones gratuitas que nos permiten interactuar con nuestros seguidores. En nuestras publicaciones en redes sociales y en nuestros eventos en Instagram Live y YouTube live, hemos tenido altos y bajos. Pasamos de tener entrevistas sin ningún tipo de entrenamiento en comunicación en septiembre del 2020, a dar un seminario en línea acerca de la comunicación en Geociencias en una prestigiosa Universidad de nuestro país. Hemos aprendido un montón de cosas que ni siquiera nos imaginamos cuando empezó este proyecto.

At the time we began GeoLchat, a social-media project with a focus on communicating scientific research, in Spanish, on these specific disciplines, didn’t exist. Our lack of professional communication training on how to better communicate our science to our scientific and non-scientific audience has been a challenge and constant learning journey. We have based our project in free apps that allow us to receive interaction with our followers. In our social media posts, and in our Instagram and YouTube-live events, we have had several pitfalls as well as successful moments. From making interviews without any communication training starting in September of 2020, to successfully giving an online seminar in geosciences communication at a major university in our home-country, we have learned what we didn’t imagine when we created this project.

Pero todos estos esfuerzos no son tarea fácil. Los periodistas científicos y los científicos dedicados a la divulgación son los expertos. Nuestra intención como jóvenes científicas con entusiasmo por comunicar nuestra ciencia es mostrar que nuestra comunidad científica no debería estar prevenida o sentirse avergonzada de comunicar sus investigaciones en espacios diferentes a artículos científicos en revistas indexadas u otros medios formales. No por hacer este ejercicio se le está restando el mérito científico a alguien, para comunicar la ciencia en lenguaje sencillo se necesita un poco más de modestia. Después de todo ¿Quienes son los más apasionados acerca de la ciencia que los mismos científicos? Haríamos un mejor trabajo con un entrenamiento profesional, pero la academia no nos lo proporciona, y sólo algunas iniciativas de diversidad, equidad e inclusión consideran la comunicación de la ciencia como parte de su plan de acción. Actualmente, muchas organizaciones profesionales ofrecen talleres y cursos para la comunicación de la ciencia, pero ninguno de estos es público y dado en idiomas diferentes al inglés, lo cual se desvía del objetivo de que cualquier persona puede entrenarse en esta disciplina y comunicar la ciencia.

But doing these efforts is not an easy task. Science journalists, and scientists dedicated to public-outreach are the experts. Our intention as young female scientists with an enthusiasm for communicating our science is to show that our scientific community should not be terrified or ashamed of communicating their findings beyond a scientific paper. After all, who is more passionate about their science than the scientists themselves? We, the scientists, would do a better job with a professional training, but academia doesn’t provide that request, and only a few DEI academic initiatives consider science-communication efforts as part of their focus actions. Today, several professional organizations offer workshops, and short-courses for science communication, but these are neither public, nor given in different languages, which misses the point of science communication for the public.

En nuestra corta experiencia hemos encontrado que comunicar la ciencia para un público no angloparlante no se trata simplemente de traducir al español, no es como traducir un libro o un artículo palabra por palabra. Cuando se traduce la ciencia, el traductor necesita saber del público al que llegará el mensaje y los elementos con los cuales el espectador se identifica. La representación cultural es la clave cuando se comunica la ciencia a públicos diferentes, esto crea una cercanía con las personas y ayuda a que el mensaje que se quiere dar llegue de manera efectiva. En GeoLchat hemos intentado traducir al español la ciencia apelando a nuestras referencias culturales como Latinoaméricanas. Esta es una de las mejores estrategias que hemos usado para atrapar la atención de nuestro público e invitarlos a que se acerquen a las Geociencias. Por ejemplo, en nuestra sección “La Pola Geológica” de conversación-entrevista en vivo, hacemos referencia a “La Pola“ tanto como una mujer clave en la independencia de Colombia en el siglo XIX, como una expresión coloquial que en Colombia se refiere a la cerveza. Éste es una de nuestras secciones más populares que ha atraído a los espectadores; se trata de un rato en el que charlamos de manera relajada con una cerveza (Pola) con un(a) científico(a) Latinoaméricano(a) a través de YouTube Live.

In our short experience, we have found that communicating science for non-English speakers is not done by sole translation, it is not like translating a book, or a paper word-by-word. When translating science, the translator needs to know the public he/she/they are appealing to and the elements that the public identifies with. Cultural representation is key when communicating science to different audiences, it gets you closer to certain people and helps you successfully deliver the message you want to give. In GeoLchat we translate science to Spanish making an appeal to our cultural LatinX references, and this is one of the strategies we have used to catch our public’s attention and invite them to approach the Geosciences. For example, in our live-interview segment, called ‘La Pola Geológica’, we reference ‘La Pola’ both as a Colombian female independentist icon from the 1800s and as a Colombian slang for beer. This is one of our most popular segments that has attracted viewers; a relaxed time chatting with us and Latin American scientists through a YouTube live, while having a Pola.

Asi como nosotras lo hemos hecho, invitamos a los científicos y comunicadores de la ciencia cuyo idioma principal no sea el inglés a tomar sus celulares y hacer el ejercicio de comunicar y divulgar la ciencia en otros idiomas diferentes al hegemónico Inglés, tales como el español y el portugués, para el caso de Latinoamérica. Creemos que la comunicación de la ciencia en otros idiomas diferentes al inglés contribuirá a que en el mundo la ciencia se haga cada vez más diversa, equitativa e incluyente.

Same as us, we are inviting scientists and science communicators who are non-English native speakers, to grab their phones and their thoughts and communicate science in languages other than English, such as Spanish and Portuguese for the Latin American case. We believe that science communication in other languages different from English will contribute to the global interest of making scientific research more equitable, diverse, and inclusive.

References

Márquez MC and Porras AM (2020) Science Communication in Multiple Languages Is Critical to Its Effectiveness. Front. Commun. 5:31. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.00031

Ramírez-Castañeda V (2020) Disadvantages in preparing and publishing scientific papers caused by the dominance of the English language in science: The case of Colombian researchers in biological sciences. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0238372. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238372

RICYT (2020) El estado de la ciencia 2020: El Estado de la ciencia en Imagenes

Ciocca, D. R. & Delgado (2017) The reality of scientific research in Latin America; an insider’s perspective G. Cell Stress Chaperones 22, 847–852.

Michelsen IM (2022) El sector de ciencia e innovacion se quedo pequeno para los phds colombianos, La Silla Vacía