A dramatic evening sky puts the frame to a photo taken during the Brazilian Antarctic expedition to James Ross Island in 2016. Brazilian palaeontologists and soil scientists together with German soil scientists spent over 40 days on the island to search for fossils and sample soils at various locations of the northern part of the island.

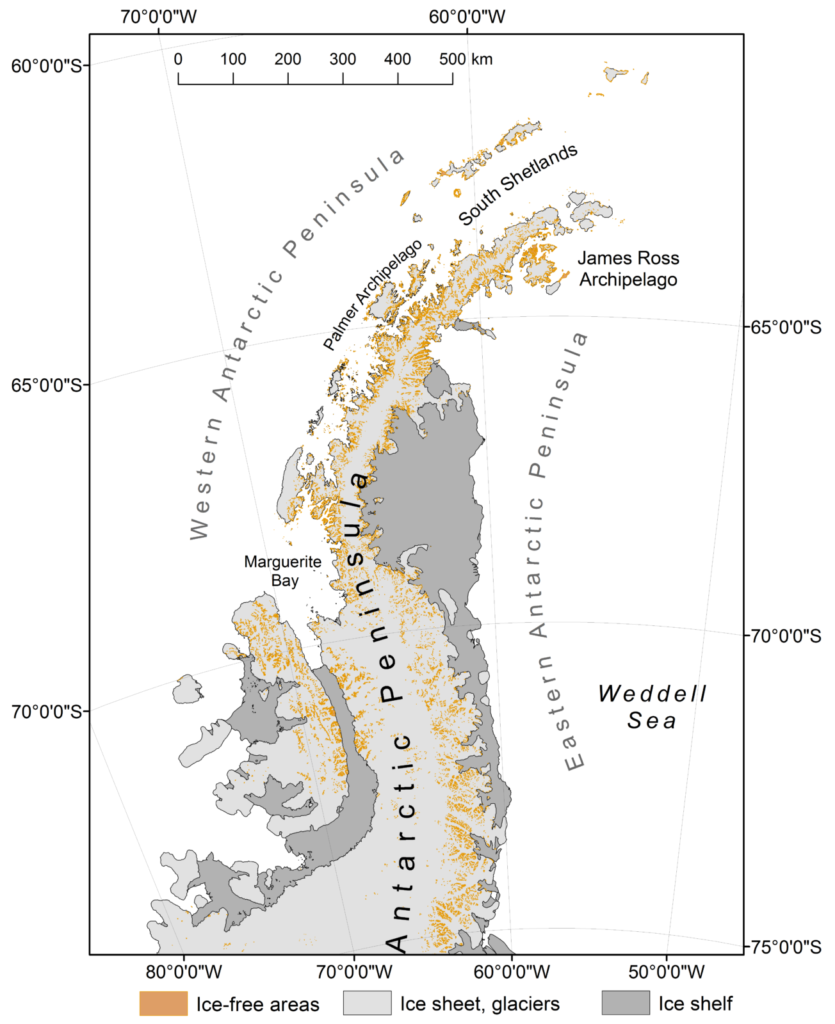

The island was named after Sir James Clark Ross who led the British expedition in 1842, which first charted locations at the eastern part of the island. James Ross Island is part of Graham Land, the northern portion of the Antarctic Peninsula, separated from South America by the stormy Drake sea passage.

Map of the Antarctic Peninsula featuring the James Ross Archipelago (Credit: The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, Antarctic Digital Database Map Viewer)

This photo was taken in the northern Ulu Peninsula, which is the northernmost part of the relatively large James Ross Island and the largest ice-free area in the Antarctic Peninsula region. The island’s characteristic appearance is formed by Late Neogene volcanic rocks (3-7 million years old) over fossil rich Late Cretaceous sandstones (66-120 million years old).

In the photo we are looking from a higher marine terrace at the Santa Martha Cove, the ‘home’ to the 2016 Brazilian Antarctic expedition, towards the steep cliffs of Lachman Crags, a characteristic mesa formed by Late Neogene lava flows. The Lachman Crags mesa, the Spanish word for tablelands, dominates the landscape of the northern part of the Ulu Peninsula. Above the cliffs visible in the photo, a glacier covered plateau stretches to the Northwest.

The marine terrace on which the tent is standing is comprised of a flat area that has been ice-free for approximately 6000 years and thus makes for a great model system to study soil development after glacial retreat. The ground is composed of a mixture of volcanic rocks and Cretaceous sandstones rich in all sorts of fossils, from fossilised wood to shark teeth, ammonites and reptile bones.

The strong winds that can start in Antarctica from one moment to the other and the very low precipitation led to the characteristic desert pavement, with stones sorted in a flat arrangement on top of the fine textured, deeply weathered permafrost soils. Although these soils host a surprisingly high number of microorganisms, most terrestrial life is restricted to wetter areas surrounding fresh water lakes and melt water streams. Thus lakes and snow meltwater-fed areas make for higher primary production of algae and mosses, fostering biodiversity and soil development by organic matter input.

As there are no larger bird rookeries on James Ross Island the only way sea-derived nutrients reach the Ulu Peninsula is by a rather grim feature: dead seal carcasses that lie distributed across the lowlands (< 150 m asl) of the Ulu Peninsula. Carcasses fertilise the soils in their direct vicinity while slowly decomposing over decades, thus feeding small patches of lichens and mosses within the barren cold arid desert. The region is thus an illustration of the harsh Antarctic environment where even Weddell seals, animals that are well adapted for the living in dense pack ice during the polar night, die when losing track on land on the way to the water.

By Carsten Müller, Technical University of Munich Chair of Soil Science, Germany

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.