Geotalk is a regular feature highlighting early career researchers and their work. In this interview we speak to Mathieu Morlighem, an associate professor of Earth System Science at the University of California, Irvine who uses models to better understand ongoing changes in the Cryosphere. At the General Assembly he was the recipient of a 2018 Arne Richter Award for Outstanding Early Career Scientists.

Could you start by introducing yourself and telling us a little more about your career path so far?

I am an associate professor at the University of California Irvine (UCI), in the department of Earth System Science. My current research focuses on better understanding and explaining ongoing changes in Greenland and Antarctica using numerical modelling.

I actually started glaciology by accident… I was trained as an engineer, at Ecole Centrale Paris in France, and was interested in aeronautics and space research. I contacted someone at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in the US to do a six-month internship at the end of my master’s degree, thinking that I would be designing spacecrafts. This person was actually a famous glaciologist (Eric Rignot), which I did not know. He explained that I was knocking on the wrong door, but that he was looking for students to build a new generation ice sheet model. I decided to accept this offer and worked on developing a new ice sheet model (ISSM) from scratch.

Even though this was not what I was anticipating as a career path, I truly loved this experience. My initial six-month internship became a PhD, and I then moved to UCI as a project scientist, before getting a faculty position two years later. Looking back, I feel incredibly lucky to have seized that opportunity. I came to the right place, at the right time, surrounded by wonderful people.

This year you received an Arne Richter Award for Outstanding Early Career Scientists for your innovative research in ice-sheet modelling. Could you give us a quick summary of your work in this area?

The Earth’s ice sheets are losing mass at an increasing rate, causing sea levels to rise, and we still don’t know how quickly they could change over the coming centuries. It is a big uncertainty in sea level rise projections and the only way to reduce this uncertainty is to improve ice flow models, which would help policy makers in terms of coastal planning or choosing mitigation strategies.

I am interested in understanding the interactions of ice and climate by combining state-of-the-art numerical modelling with data collected by satellite and airplanes (remote sensing) or directly on-site (in situ). Modelling ice sheet flow at the scale of Greenland and Antarctica remains scientifically and technically challenging. Important processes are still poorly understood or missing in models so we have a lot to do.

I have been developing the UCI/JPL Ice Sheet System Model, a new generation, open source, high-resolution, higher-order physics ice sheet model with two colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory over the past 10 years. I am still actively developing ISSM and it is the primary tool of my research.

More specifically, I am working on improving our understanding of ice sheet dynamics and the interactions between the ice and the other components of the Earth system, as well as improving current data assimilation capability to correctly initialize ice sheet models and capture current trends. My work also involves improving our knowledge of the topography of Greenland and Antarctica’s bedrock (through the development of new algorithms and datasets). Knowing the shape of the ground beneath the two ice sheets is key for understanding how an ice sheet’s grounding line (the point where floating ice meets bedrock) changes and how quickly chunks of ice will break from the sheet, also known as calving.

At the General Assembly, you presented a new, comprehensive map of Greenland’s bedrock topography beneath its ice and the surrounding ocean’s depths. What is the importance of this kind of information for scientists?

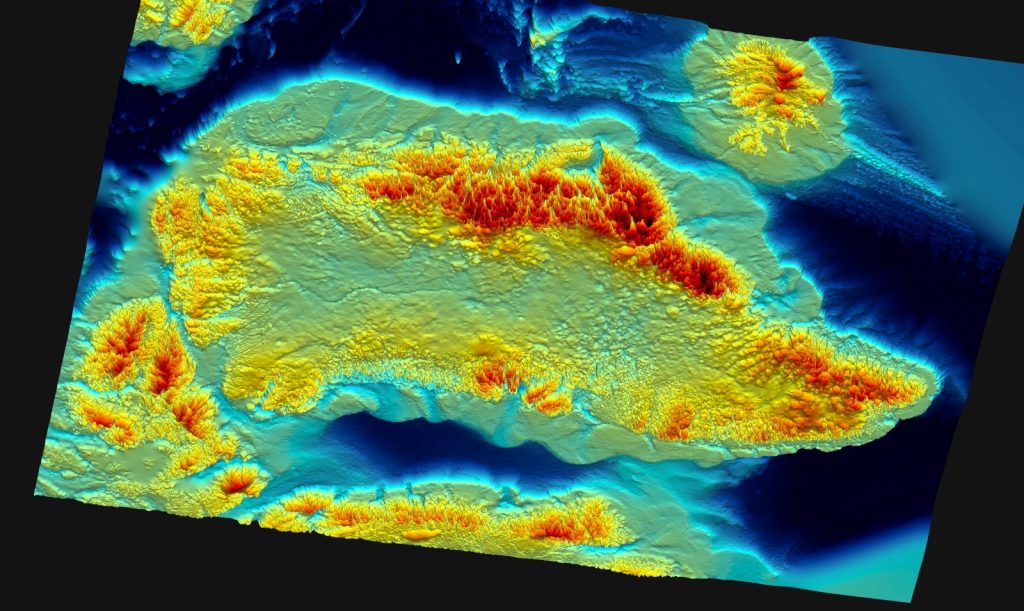

I ended up working on developing this new map because we could not make any reliable simulations with the bedrock maps that were available a few years ago: they were missing key features, such as deep fjords that extend 10s of km under the ice sheet, ridges that stabilize the retreat, underwater sills (that act as sea floor barriers) that may block warm ocean waters at depth from interacting with the ice, etc.

Subglacial bed topography is probably the most important input parameter in an ice sheet model and remains challenging to measure. The bed controls the flow of ice and its discharge into the ocean through a set of narrow valleys occupied by outlet glaciers. I am hoping that the new product that I developed, called BedMachine, will help reduce the uncertainty in numerical models, and help explain current trends.

3D view of the bed topography and ocean bathymetry of the Greenland Ice Sheet from BedMachine v3 (Credit: Peter Fretwell, BAS)

How did you and your colleagues create this map, and how does it compare to previous models?

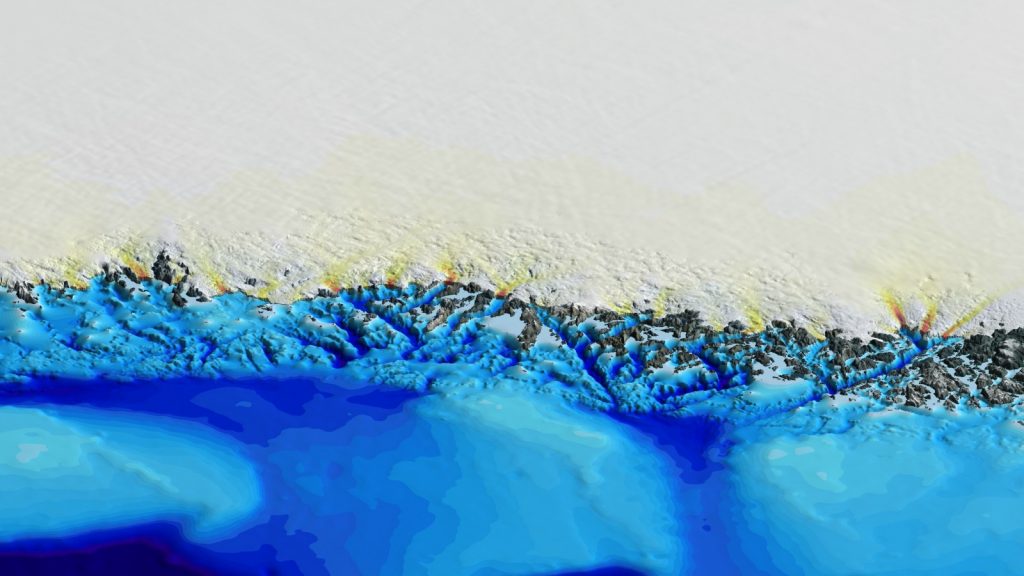

The key ingredient in this map, is that a lot of it is based on physics instead of a simple “blind” interpolation. Bedrock elevation is measured by airborne radars, which send electromagnetic pulses into the Earth’s immediate sub-surface and collect information on how this energy is reflected back. By analyzing the echo of the electromagnetic wave, we can determine the ice thickness along the radar’s flight lines. Unfortunately, we cannot determine the topography away from these lines and the bed needs to be interpolated between these flight lines in order to provide complete maps.

During my PhD, I developed a new method to infer the bed topography beneath the ice sheets at high resolution based on the conservation of mass and optimization algorithms. Instead of relying solely on bedrock measurements, I combine them with data on ice flow speed that we get from satellite observations, how much snow falls onto the ice sheet and how much melts, as well as how quickly the ice is thinning or thickening. I then use the principle of conservation of mass to map the bed between flight lines. This method is not free of error, of course! But it does capture features that could not be detected with other existing mapping techniques.

3D view of the ocean bathymetry and ice sheet speed (yellow/red) of Greenland’s Northwest coast (Credit: Mathieu Morlighem, UCI)

What are some of the largest discoveries that have been made with this model?

Looking at the bed topography alone, we found that many fjords beneath the ice, all around Greenland, extend for 10s and 100s of kilometers in some cases and remain below sea level. Scientists had previously thought some years ago that the glaciers would not have to retreat much to reach higher ground, subsequently avoiding additional ice melt from exposure to warmer ocean currents. However, with this new description of the bed under the ice sheet, we see that this is not true. Many glaciers will not detach from the ocean any time soon, and so the ice sheet is more vulnerable to ice melt than we thought.

More recently, a team of geologists in Denmark discovered a meteorite impact crater hidden underneath the ice sheet! I initially thought that it was an artifact of the map, but it is actually a very real feature.

More importantly maybe, this map has been developed by an ice sheet modeller, for ice sheet modellers, in order to improve the reliability of numerical simulations. There are still many places where it has to be improved, but the models are now really starting to look promising: we not only understand the variability in changes in ice dynamics and retreat all around the ice sheet thanks to this map, we are now able to model it! We still have a long way to go, but it is an exciting time to be in this field.

Interview by Olivia Trani, EGU Communications Officer