When we think of hydropower, its environmental impacts usually comes to mind: the dams that disrupt ecosystems, the water bodies that shift, the surface evaporation that increases, and the greenhouse gases that escape from reservoirs1. Hydropower, for all its clean energy potential, is not without its environmental baggage, whether on local water resources or the global surface water storage.

But how often do we consider the reverse: how does climate itself affect hydropower? Is it a chicken-and-egg problem, where one causes the other? Or is it something more complex, a positive feedback loop in which climate and hydropower continuously shape each other’s fates?

The Climate-Hydropower Dilemma

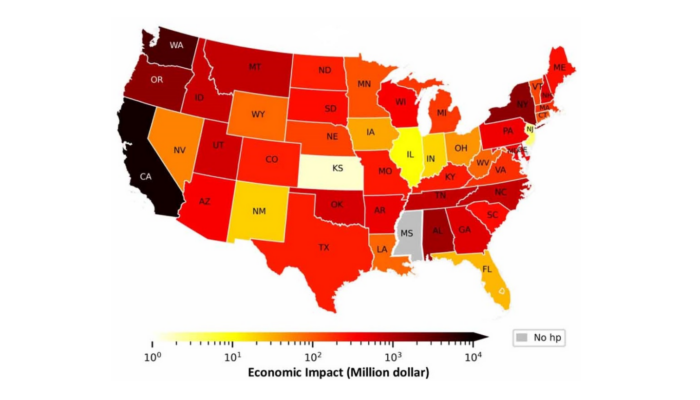

A recent study takes a different angle and explores how droughts and their intensification under climatic changes are directly reducing the capacity of hydropower in the U.S. over the past two decades (2003-2020): droughts caused a loss of 300 million megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity generation, a staggering number that led to $28 billion in economic damage.

The US is not alone. A quarter of Chinese hydropower plants are to experience a reduction of >20% in future hydroelectricity generation (2031–2060). Portugal may get hit by reduction of 11% to 38% in short- (2031–2060) to long-term (2071–2100).

It’s a truism that climate change, e.g. drought, has a profound effect on hydropower. But didn’t we already know that? Or is that the end of the story? Not quite!

Moghaddasi et al. (2024) unpacks the dilemma of climate-hydropower dynamics: while droughts diminish hydropower production, the operation of hydropower itself would contribute to climate change. This raises a critical question: is hydropower just a victim of droughts, or in return it also perpetuates climate change that it suffers from?

A Chicken or Egg Problem—or Both?

The interplay of hydropower and climate is not a linear cause-and-effect scenario. In fact, it might be better understood as a positive feedback loop. As climate change intensifies droughts, it reduces water availability and undermines the reliability of hydropower energy. In response, energy grids have to shift to more carbon-intensive alternatives, such as natural gas, to continue functioning.

This shift leads to the release of ~162M tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other harmful pollutants like sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), which exacerbate global warming.

This brings us back to the chicken-and-egg dilemma: is hydropower simply a cause of climate change, or is it also a contributor? It seems to be both, hence the dilemma.

The Unspoken Feedback Loop

It’s not just about climate affecting hydropower or vice versa. These two forces are locked in a feedback loop. Every time drought reduces water availability for hydropower, we burn more fossil fuels to compensate, releasing more greenhouse gases. Those emissions, in turn, warm up the planet and intensify droughts. This vicious cycle goes on degrading environmental and energy systems, leading to environmental insecurity.

In other words, the bigger hydropower producing states are more prone to droughts, and hence bigger producer of polluting emissions. This dilemma is starkly visible in states like California and Washington, ranking among the most vulnerable to this drought-hydropower vicious cycle.

As Washington alone produces ~27% of the country’s hydropower, every drought that hits the state triggers a larger consumption of natural gas with associated emissions compared to states with less reliance on hydroelectricity. As droughts intensify so will the feedback loop.

On the other hand, hydropower generation in arid states like Nevada, with historically weaker coupling of drought and hydroelectricity, is less vulnerable to droughts. Why? This is a fascinating hydrological example of multi-faceted interactions among soil moisture, annual rainfall, reservoir storage size (see section 3.4. of the study for more details).

What Can Be Done? Break the Cycle

Breaking this vicious cycle is a daunting challenge that requires interventions that both address the effects of climate change and the structural vulnerabilities of the hydropower. So, what can be done? This is what they suggest:

- Diversify the energy mix beyond solely hydropower solutions.

- Smarter water management strategies, including smarter water conservation and forecasting systems.

- Climate-resilient infrastructures particularly during low-flow periods.

Epilogue: A Paradox of Power

As droughts become more frequent, the question is no longer just about whether climate change affects hydropower—it’s about how the hydropower industry will respond. The relationship between hydropower and climate is not a one-way street; it’s a dynamic system where both affect each other in profound ways.

The paradox of hydropower is that while it’s one of our cleanest forms of energy, it’s also a system deeply intertwined with the climatic changes it seeks to mitigate. As we continue to grapple with climate change, localized understanding and stakeholder-informed interventions to break this feedback loop is crucial.

Hydropower is not just a victim of climate change, but an active participant in the larger narrative of global water and energy nexus. Breaking this cycle will require innovation, smarter policies, and concerted efforts to address both sides of the equation. If we succeed, we might just secure a future where hydropower remains a valuable part of the energy mix, without being at the mercy of the planet’s shifting climate.

Edited by Sina Khatami

On behalf of the EGU community, we’d like to also congratulate Prof Hamid Moradkhani, Alton N. Scott Endowed Professor at The University of Alabama, for being elected as a 2024 AGU Fellow in recognition of his pioneering research in complex water and environmental systems.