During the month of February, we are focusing on ‘Accessibility and Inclusivity’ here at the EGU. Although these topics are clearly relevant to the General Assembly, some people may wonder whether they also relate to scientific research. Clearly all geoscientists are people, so accessibility and inclusivity matter regardless of what scientific discipline they are in. But there can also be tangible benefits to traditional geoscience research when scientists apply different techniques that are more inclusive.

A recent paper published in Hydrology and Earth System Sciences led by Bocar Sy, demonstrates this perfectly. The goal of this study was to find out the extent and depth of historical flooding events in Yeumbeul North, near Dakar in Senegal, but no data had ever been collected on these floods. Dakar is particularly vulnerable to flooding due to its densely packed communities. Flooding in this area is generally considered to be caused by runoff and rainwater combined with ineffective drainage and high groundwater levels. So, the authors decided to adopt a citizen science approach by interviewing local representatives and locally nominated delegates (called ‘neighbourhood chiefs’ by residents) and using a type of mapping done by collaboratively by people involved in the study (a technique called ‘participatory mapping’). Their main aim was to discover the extent, severity and chain of events for three historical floods.

To collect the necessary data, the researchers interviewed the neighbourhood chiefs and local representatives who had witnessed or experienced the three floods, asking them to recall their experiences and then describe in detail information related to the events. To collect all relevant information, the people interviewed were asked to describe a range of things that may have influenced the flood: everything from broken pipes to what local authorities did or didn’t do during the events. They were also asked about places they remembered seeing the floodwaters and what their personal experiences of the flooding were. The neighbourhood chiefs were also trained in how to read and use a map, then took part in the participatory mapping exercise to generate additional data about the extent and depth of the floods.

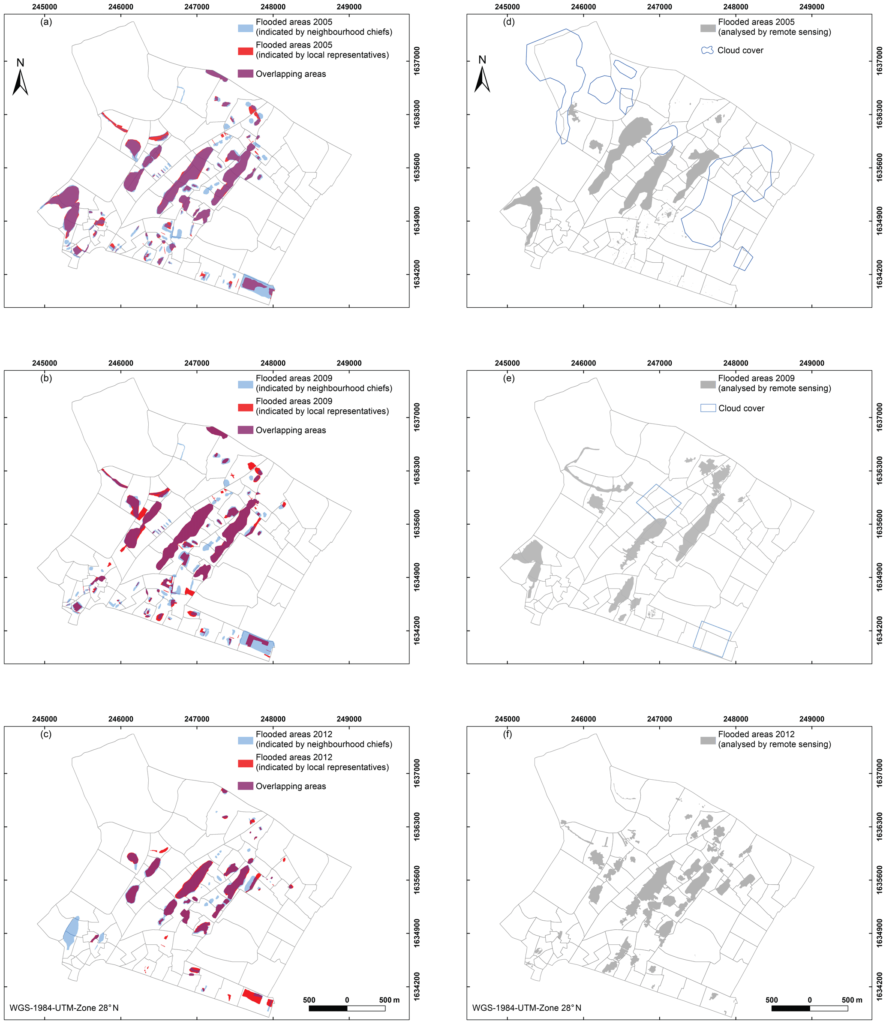

Spatial distribution of flooded areas based on citizen science techniques in (a) 2005, (b) 2009 and (c) 2012. Flooded areas based on remote sensing data in (d) 2005, (e) 2009 and (f) 2012, from Sy et al (2020).

To check the reliability of the data collected, the researchers compared it with remote sensing data from the same time period. They found that the spatial extent of both the citizen science data and the remote sensing data were pretty similar. Moreover, the local residents were able to identify several natural and human issues that were a part of the chain of events that caused each flood, which was vital information for understanding how floods in this area develop. Because the participants were encouraged to use their own words and language, they were also able to highlight factors that non-residents might never have thought to include and provided a much more detailed understanding of the extent of the flooding than the local authorities.

The authors of this paper also reported another benefit beyond collecting historical flooding data. In order for flood mitigation plans to be effective, the authors state clearly that local people must be involved at the core of flood hazard assessment and zoning. By taking part in this study, those local Dakar representatives and neighbourhood chiefs gained useful skills in flood data collection and were trained in map use and creation, all of which makes them much better able to become involved with flood risk decision-making processes and act as conduits to their neighbourhoods.

One of the key findings this paper demonstrates, is the way that including underrepresented voices in scientific data collection can be of benefit both to researchers AND to local communities. Science subjects can often be seen as exclusive by those on the outside, but by sharing knowledge and passion, and creating spaces where different ideas from diverse voices are equally heard, scientists have the potential to make geoscience more relevant for everyone.