What are the most interesting, cutting-edge and compelling research topics within the scientific areas represented in the EGU divisions? Ground-breaking and innovative research features yearly at our annual General Assembly, but what are the overarching ideas and big research questions that still remain unanswered? We spoke to some of our division presidents and canvased their thoughts on what the current Earth, ocean and planetary hot topics will be.

There are too many to fit in a single post so we’ve brought some of them together in a series of posts which will tackle three main areas: the Earth’s past and its origin, the Earth as it is now and what its future looks like, while the final post of the series will explore where our understanding of the Earth and its structure is still lacking. We’d love to know what the opinions of the readers of GeoLog are on this topic too, so we welcome and encourage lively discussion in the comment section!

The Earth’s past and its origin

Rephrasing the famous sentence by James Hutton, i.e. the present is the key to the past, we can even say that the past is the key to the future – a better understanding of past Earth processes can help understand why and how our planet evolved to have oceans, an atmosphere, a planetary magnetic field as well as the ability to sustain life. Not only that, a greater understanding of the Earth’s past can aid in finding solutions to present day problems. A strong interdisciplinary research effort is required to delve into the Earth’s past and that makes it one of the most important geoscience hot topics, albeit very broad.

Life on Earth and the physical environment

Zircons in rocks from Jack Hills in Western Australia provide evidence of oceans 4.4 b.y. ago and of conditions that may have haboured life. The remarkable thing is that these rocks are 300 million years older than the 3.8 billion year old rocks from Greenland, which were thought to hold the oldest evidence for life on Earth, until now.

Jack Hills, Western Australia. Image by Robert Simmon, based on data from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Cover Facility

These findings are no doubt very exciting, but they also go hand in hand with gaining a greater understanding about the physical environment in which these early life forms evolved. According to Helmut Weissert, President of the Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Palaeontology Division (SSP), understanding the co-evolution of life and the physical environment in Earth’s history is one of the biggest challenges for current and future scientists. Understanding past changes of the System Earth will facilitate the evaluation of man’s role as a major geological agent affecting global material and geochemical cycles in the Anthropocene.

The work of scientists in the SSP fields on understanding how the evolution of life was affected by major climatic perturbations is particularly timely, given the ongoing debate as to whether the presence of humans on Earth is potentially driving a sixth mass extinction event. Not only that, a big research question still unanswered is how did catastrophic events during the Earth’s history also affect evolutionary rates?

Developing new models and tools which might aid investigation in these areas is at the forefront of challenges to come, along with a greater interaction between related disciplines, for instance (but of course, not limited to!) the geosciences and genetics.

A changing inner Earth

The Earth’s magnetic field is one of ingredients for the presence of life on Earth, because it screens most of the cosmic rays that otherwise would penetrate in major quantities into the atmosphere and reach the surface, being dangerous for human health.

“A recent discovery is that the absence of magnetic field would cause serious damages not only to humans through a significant increase of cancer cases, but also to plants”, say Angelo De Santis, President of the Earth Magnetism and Rock Physics Division (EMRP), “implying that geomagnetic field reversals characterised by times with very low intensity of the field, would have serious implications for life on the planet”.

Another way to understand this aspect would be to have a look at the past. One of the (many) tools which can be used to understand what our planet might have looked like in its infancy is palaeomagnetism. This is especially true when it comes to one of the biggest conundrums of the Precambrian: when did plate tectonics, as we understand them now, start?

That there was perhaps some form of plate motions in the Earth’s early life is likely, but exactly what the style of those plate motions were during the Precambrian is still highly debated. Palaeomagnetic directions measured over time are used to estimate lateral plate motions associated with modern day style plate tectonics involving subduction. If similar plate motions can be identified in rocks younger than 500Ma then they might support lateral plate motions early in the Earth’s history. This, says Angelo De Santis, is one of the most exciting areas of research within Earth magnetism.

Earth Magnetic Field Declination from 1590 to 1990 by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons . Click on the image to see how the field changes over time.

Not only that, studying the strength of the geomagnetic field (which is generated in the liquid outer core by a process known as the geodynamo) and how it changes over different time scales can give us information about the early inner structure of the planet. For instance, news of a new date for the age of the formation of the inner core, after researches identified the sharpest increase in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field, hit the headlines recently. The findings imply that maybe some of the views Earth scientists hold about the core of the Earth might need to be revised!

Which leads us onto secular variation – the study of how the geomagnetic field changes, not only in strength but also in direction – because if the early core is different to how it was previously thought, is the understanding of secular variation also affected? The implications are far reaching, but a highlight, according to Angelo De Santis, has to be how the findings might affect how periods of large change (more commonly known as geomagnetic reversals) are understood. Therefore, it is key that the evolution of the geodynamo is better understood, so that scientists might be able to assess the possibility of an imminent excursion (a large change of the field, but not a permanent flip of the direction) or reversal.

From the inner Earth to the surface

If studying the inner depths of the Earth in the past might give us clues about the present and future of the planet’s core, so to on and above the surface the past can be the key to the future.

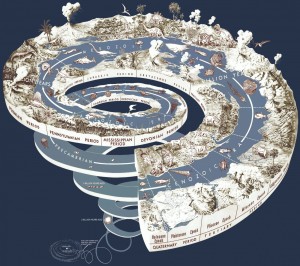

Geological time spiral by United States Geological Survey – Graham, Joseph, Newman, William, and Stacy, John, 2008, The geologic time spiral—A path to the past (ver. 1.1): U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 58, poster, 1 sheet. Available online at http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2008/58/. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

Present day climate change is a given, but predictions of how the face of the Earth might change as a result remain difficult to make while, at the same time, its consequences are not yet fully understood. Studying the climate of the past and how the biosphere, oceans and the Earth’s surface (including erosion and weathering processes), responded to abrupt and potentially damaging changes in Earth’s past climate provides a starting point to make forecasts about the future.

“A better time resolution of geological archives means we are able to further test present day climate, weathering and ocean models,” says SSP President Helmut Weissert.

And so, not only does the past tell us where we come from and how the Earth became the only planet in our Solar System capable of sustain complex forms of life, a better understanding of its origins and past behaviour might just help us improve the future too.

Next time, in the Geosciences hot topics short series, we’ll be looking at our understanding of the Earth as we know it now and how we might be able to adapt to the future. The question of how we develop the needs for an ever growing population in a way that is sustainable opens up exciting research avenues in the EMRP and SSP Divisions, as well as the Energy, Resources and the Environment (ERE), Seismology (SM) and Earth and Space Science Informatics (ESSI) Divisions.

Pingback: GeoLog | Geoscience hot topics – The finale: Understanding planet Earth

Pingback: GeoLog | Geoscience hot topics – Part II: the Earth as it is now and what its future looks like