NASA scientists have revealed surprising new information about Jupiter’s magnetic field from data gathered by their space probe, Juno.

Unlike earth’s magnetic field, which is symmetrical in the North and South Poles, Jupiter’s magnetic field has startlingly different magnetic signatures at the two poles.

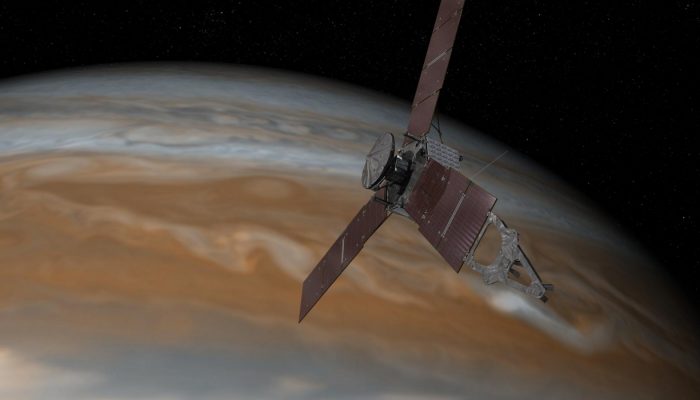

The information has been collected as part of the Juno program, NASA’s latest mission to unravel the mysteries of the biggest planet in our solar system. The solar-powered spacecraft is made of three 8.5 metre-long solar panels angled around a central body. The probe (pictured above) cartwheels through space, travelling at speeds up to 250,000 kilometres per hour.

Measurements taken by a magnetometer mounted on the spacecraft have allowed a stunning new insight into the planet’s gigantic magnetic field. They reveal the field lines’ pathways vary greatly from the traditional ‘bar magnet’ magnetic field produced by earth.

Jupiter’s magnetic field is enormous. if magnetic radiation were visible to the naked eye, from earth, Jupiter’s magnetic field would appear bigger than the moon. Credit: NASA/JPL/SwRI

The Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the movement of fluid in its inner core called a dynamo. The dynamo produces a positive radiomagnetic field that comes out of one hemisphere and a symmetrical negative field that goes into the other.

The interior of Jupiter on the other hand, is quite different from Earth’s. The planet is made up almost entirely of hydrogen gas, meaning the whole planet is essentially a ball of moving fluid. The result is a totally unique magnetic picture. While the south pole has a negative magnetic field similar to Earth’s, the northern hemisphere is bizarrely irregular, comprised of a series of positive magnetic anomalies that look nothing like any magnetic field seen before.

“The northern hemisphere has a lot of positive flux in the northern mid latitude. It’s also the site of a lot of anomalies,” explains Juno Deputy Principal Investigator, Jack Connerney, who spoke at a press conference at the EGU General Assembly in April. “There is an extraordinary hemisphere asymmetry to the magnetic field [which] was totally unexpected.”

NASA have produced a video that illustrates the unusual magnetism, with the red spots indicating a positive magnetic field and the blue a negative field:

Before its launch in 2016, Juno was programmed to conduct 34 elliptical ‘science’ orbits, passing 4,200 kilometres above Jupiter’s atmosphere at its closest point. When all the orbits are complete, the spacecraft will undertake a final deorbit phase before impacting into Jupiter in February 2020.

So far Juno has achieved eleven science orbits, and the team analysing the data hope to learn more as it completes more passes. “In the remaining orbits we will get a finer resolution of the magnetic field, which will help us understand the dynamo and how deep the magnetic field forms” explains Scott Bolton, Principal Investigator of the mission.

The researchers’ next steps are to examine the probe’s data after its 16th and 34th passes meaning it will be a few more months before they are able to learn more of Jupiter’s mysterious magnetosphere.

By Keri McNamara, EGU 2018 General Assembly Press Assistant

Further reading

Connerney, J. E. P., Kotsiaros, S., Oliversen, R. J., Espley, J. R., Joergensen, J. L., Joergensen, P. S., et al. A new model of Jupiter’s magnetic field from Juno’s first nine orbits. Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 2590–2596. 2018

Bolton, S. J. et al. Jupiter’s interior and deep atmosphere: The initial pole-to-pole passes with the Juno spacecraft, Science, 356(6340), p. 821 LP-825. 2017

Guillot, T. et al. A suppression of differential rotation in Jupiter’s deep interior, Nature. Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved., 555, p. 227. 2018