When I first began analysing agricultural pressures in German river networks, I expected the familiar story of nutrient loads, pesticide traces and differences between landscapes. What I did not expect was how narrow the ecological safe operating space has become for many rivers. Even small increases in agricultural pressure, especially from pesticides, reduced the likelihood of achieving good ecological status in a clear and consistent way. Seeing this pattern emerge across so many catchments made me look more closely at how agriculture and hydrology interact, and why understanding these pathways matters not only for research but also for river management. For me, this matters because rivers often show signs of stress long before the damage becomes visible, and recognising these early signals has become central to how I want to contribute as a scientist.

Agriculture is vital to Europe’s food system, but the way it is practised today shapes the condition of our rivers. These rivers support biodiversity, supply water and shape local landscapes, which is why their decline concerns all of us. Large fields, specialised crops, high fertiliser use and routine pesticide treatments help secure yields, yet they also increase the chance that nutrients and chemical residues move from land to water. Many rivers already face pressures from channel modification, drainage or urban development, which reduces their ability to recover once additional loads arrive.

From simple agricultural land-use fractions to Land Use Intensity Index for Stream Ecosystems (LUIS)

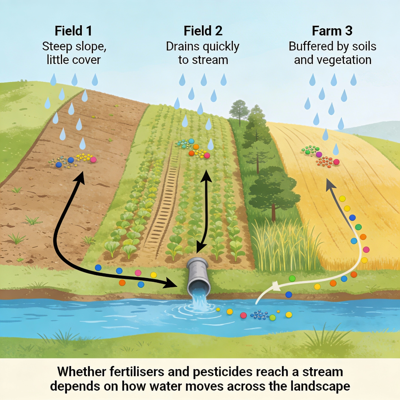

A key lesson for me has been that whether substances applied to fields reach a stream depends strongly on how water moves across the landscape. Topography, soil type, vegetation cover, artificial drainage and distance to the channel all influence how rainfall becomes runoff. Some fields drain quickly into nearby streams, while others are buffered by soils, slopes or riparian vegetation. Yet many assessments still rely on the proportion of agriculture in a catchment, a simple measure that ignores these hydrological pathways.

Conceptual illustration of hydrological connectivity between agricultural fields and streams (AI-generated illustration based on the author’s description).

To address this gap, our team at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research developed the Land Use Intensity Index for Stream Ecosystems (LUIS) (Agyekum et al., 2025). LUIS combines crop‑specific fertiliser inputs, pesticide use and how easily rain runoff can carry these substances to nearby streams, using national data on typical fertiliser and pesticide applications and mapping how pollutants move from fields into nearby streams and rivers. In practice, it highlights where agricultural pressure is most likely to reach streams, not just where agriculture appears on a map.

When we applied LUIS across Germany and compared the results with ecological status assessments under the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), a clear pattern appeared: ecological status declined steadily as agricultural pressure increased. This finding matches national reporting by the German Environment Agency, which shows that only a small share of German rivers currently reach good ecological status.

Among all components, pesticide intensity showed the strongest and most consistent association with ecological degradation. The effect was especially pronounced in headwater streams, which respond quickly to runoff and offer little dilution. These streams form a large share of the river network and strongly influence downstream conditions, as highlighted by the FLOW small-stream initiative in Germany.

A Narrow Safe Operating Space

Another important result involved thresholds. We wanted to understand how much agricultural pressure rivers can tolerate before the probability of achieving good ecological status begins to fall. The thresholds occurred at modest levels already common in many agricultural regions, revealing a narrow safe operating space. This is not only a German problem. Diffuse agricultural pollution remains one of the main pressures on European waters, as highlighted by the European Environment Agency.

LUIS does not explain ecological status completely. Rivers respond to several pressures at once, including channel alteration, floodplain disconnection, wastewater discharges and long-term pollutants. Biological assessments also integrate conditions across time and space. LUIS therefore identifies potential pressure rather than providing proof of impact. Its value lies in offering a spatially consistent way to understand where agricultural influences are most likely to occur.

Why does this matter for the Water Framework Directive (WFD)?

These findings become especially relevant in the context of the Water Framework Directive, the main EU law for protecting and restoring rivers. The Directive requires all surface waters to reach at least good ecological status. This includes chemical quality, fish, invertebrates, aquatic plants and the physical structure of rivers. Member States must identify pressures, prepare river basin management plans and implement measures such as pollution reduction and habitat restoration.

Europe has completed two WFD cycles, yet many waters still fall short of good status. The year 2027 is the final target, with only limited exemptions allowed. For me, this is where hydrology-based indicators become essential. Many headwater streams already sit close to ecological thresholds. If policy actions focus only on rivers that are visibly degraded, measures may come too late for the WFD goals to be met.

This is also where the broader relevance becomes clear. These rivers supply drinking water, support biodiversity and connect rural and urban landscapes. Their decline affects ecosystems, communities and future restoration costs. Knowing where pressure is rising gives us a chance to act early and more effectively.

For me, the message is straightforward. If Europe wants its rivers to recover, we cannot wait for problems to become visible. Managing pressure while rivers are still close to good condition is far more effective than attempting to repair damage later. Hydrology-based tools such as LUIS do not replace monitoring or regulation, but they help anticipate where the next challenges will emerge.

The underlying study is available in Communications Earth & Environment:

A hydrologically informed agricultural land use intensity index for stream ecosystems.

edited by B. Schaefli