Have you ever heard that we can “weigh” water on Earth from space?

Since 2002, the GRACE and GRACE-FO satellite missions have been mapping month-to-month variations of the Earth’s gravity field. Because gravity responds to mass, these data can reveal how water is redistributed at the surface and in the subsurface.

The result is a global time series of terrestrial water storage anomalies (TWSA)—how total water storage deviates from its long-term average.

Many hydrologists and water-resources researchers use GRACE/GRACE-FO to estimate groundwater storage changes. A standard approach is to subtract estimates of soil moisture, snow, surface water, and glacier mass from GRACE total water storage anomalies—so the remainder approximates groundwater changes.

However, most Water Storage Compartment (WSC) products such as soil moisture, snow-water equivalent, surface water storage, glacier mass – have a finer spatial resolution and more local variability than GRACE. As a result, subtracting these products from GRACE can introduce misleading residuals. Fine details from the WSCs can “sneak into” the GRACE residual and can be wrongly interpreted as groundwater.

Figure 1 above illustrates this core problem: GRACE provides a smooth, large-scale picture, while many other water-storage products contain much finer detail. If we combine them without matching their “focus”, the result can be misleading.

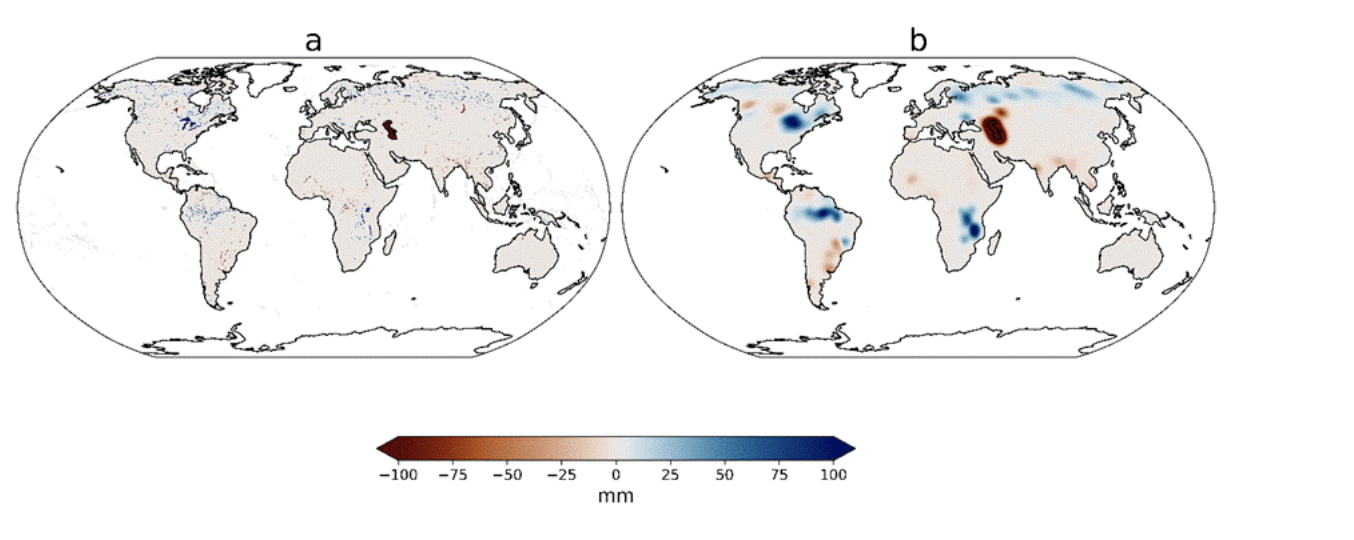

To avoid this, the WSCs need to be filtered so that they represent water storage at the same effective resolution at which GRACE “sees” them (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example surface water storage anomaly: left, unfiltered (fine texture, local detail); right, after applying a Gaussian filter with 250 km filter width (fine texture suppressed; large-scale structure retained).

So how can we overcome this challenge? How should we filter non-GRACE water storage data so they become compatible with GRACE before comparison or subtraction?

In our recent HESS paper, we tested two possible approaches. We remapped products to a common 0.5° grid, converted them to the same units, and removed long-term trends. Then, there were two ways to go.

Applying GRACE-Style Filters to WSCs

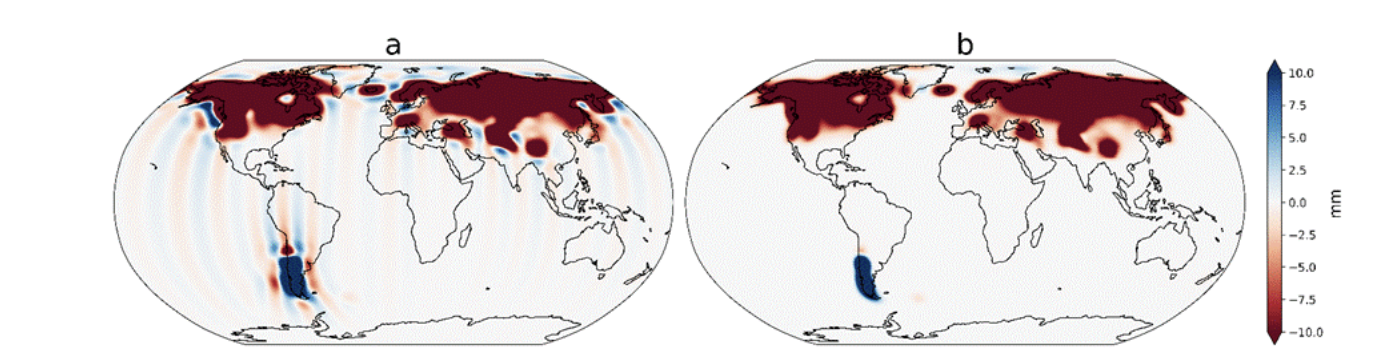

GRACE maps often contain north–south “striping” patterns caused by measurement and data processing, e.g. almost similar to figure 3a. Our first potential solution was to treat WSCs like GRACE itself. We apply the widely used GRACE decorrelation filter – often called DDK or VDK – which is designed to remove stripe noise from GRACE.

But there is a problem: the non-GRACE products are built with completely different instruments, retrieval methods, and error patterns. Their noise is not GRACE’s noise.

For this approach, the results showed visible north–south striping over the globe. These stripes are not geophysical signals – they are artefacts created by applying a GRACE-specific filter to a non-GRACE data structure.

In other words, the filter designed to remove stripes from GRACE can create stripes when mis-applied to other products (Figure 3).

Applying a Gaussian Filter to WSCs

The second option was to smooth the WSC data with a simple, round, bell-shaped (Gaussian) filter, testing different blur widths from about 50 to 600 km. Using spatial autocorrelation, we selected the most appropriate filter width that has a similar spatial resolution to GRACE and allows for subtraction.

In our results we found that a value of about 250 km works best. At this scale, the smoothed WSC data have almost the same spatial “smoothness” as GRACE-TWSA.

Figure 3. Two global maps of monthly snow-water equivalent anomalies. Panel (a) shows artificial vertical stripe artefacts after applying a GRACE-style filter to a non-GRACE product. Panel (b) shows the same month after applying a 250 km Gaussian filter on the grid – structure is smoother, without stripe artefacts.

Practical Takeaways

If you subtract apples from oranges, you get a strange fruit. The same is true here:

- If WSC data sets are sharper than GRACE-TWSA, their fine details can “sneak” into the GRACE residual and be wrongly interpreted as groundwater changes..

- If you use an inappropriate filter, you can add stripe-like artefacts that look like real changes in water storage– especially when you later integrate or average in time.

Our recipe— a 250 km Gaussian filter on the WSCs, chosen by matching spatial autocorrelation to GRACE—makes the subtraction fairer. It gives each component a similar effective spatial resolution before we infer groundwater. That, in turn, makes the residual more trustworthy for detecting large-scale and long-term groundwater storage changes.

Remember, the goal is comparable resolution, not pretty maps. We do not smooth to make the maps prettier; we are enforcing a common effective spatial resolution so that the groundwater residual reflects real changes in water storage, rather than artefacts of the data processing.

Curious to try this yourself? You don’t need to be a GRACE specialist – the processed groundwater storage time series are freely available through the GravIS portal, where you can explore interactive maps or download the data for your own analyses.

Want to dig deeper?

- Paper (open access):

Sharifi et al. (2025), Technical note: GRACE-compatible filtering of water storage data sets via spatial autocorrelation analysis, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-6985-2025

- G3P groundwater storage data sets: https://doi.org/10.5880/G3P.2024.001

- Global Gravity-based Groundwater Product (G3P) project page: https://www.gfz.de/en/section/hydrology/projects/g3p-global-gravity-based-groundwater-product

- GravIS portal to view and download G3P water storage data sets: https://gravis.gfz.de/gws

- Overview of the GRACE and GRACE-FO missions https://www.gfz.de/en/section/global-geomonitoring-and-gravity-field/projects/closed-projects/grace-gravity-recovery-and-climate-experiment-mission

- General info on water storage from satellite gravimetry: https://www.globalwaterstorage.info/en/

Edited by Bettina Schaefli;

A note from the editorial team: This is a guest blogger contribution received following a recent innovation in the Copernicus Publishing System: upon acceptance of your paper in one of our journals, authors are invited to consider if they would like to turn their science paper into a blog post.